Signs of a new inclusiveness?

Texas Monthly‘s special edition

By Dick J. Reavis / The Rag Blog / May 25, 2010

The current issue of Texas Monthly, a “special edition” whose theme is “Where I’m From” is worth some reading, some scrutiny, and some thought.

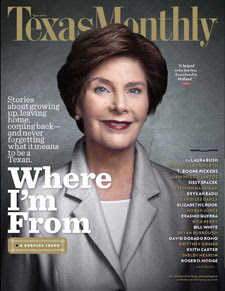

Though the funerary photo of Laura [Eva von Braun] Bush on its cover is an eyesore, its teaser lines carry an eye-raising message. Nineteen contributors and interviewees — mostly notables and novelists — are named there: four of them are Mexican-American, two of them black.

With luck, the issue’s inclusiveness forecasts a new and better day at the magazine. It’s as if Texans, and all Texans, could produce a national-class magazine without heavy supervision from the non-Texans who dominate the state’s industry of words.

A few weeks ago, Mexican-American writers chastised the editors of both the Texas Observer and the Monthly for accepting slots on a panel of 11 other whites at an Observer-sponsored “Texas Writer’s Festival.” From the sidelines I assailed them for billing non-Texan whites as homefolk.

But the Monthly’s special edition would have already been at its printer — outside of Texas — when the controversy arose, and that might indicate that the magazine, or at least its editor, Jake Silverstein, had already turned a corner, if only for a single issue.

The significance of “Where I’m From,” however, goes beyond questions of color and regional origin. As a commercial product, this artifact is an oddity. Mass-market magazines are generally aimed at prosperous and prospering readers 25 to 40 because that’s the demographic advertisers seek.

The Monthly’s “From” issue mainly carries accounts of life in Texas before 1970, certainly before 1985. In the annals of the industry’s prized readership, anything before 1985 is history, and anything before 1970 is ancient history — and as Henry Ford long ago told us, for Americans “history is bunk.”

If not many young people will turn the pages of this edition, their parents will, and that probably explains either its origin — or merely its commercial convenience. The magazine’s paid pages include a 42-page advertorial from institutions of higher learning: private and public colleges alike are seeking students who pay full tuition. The issue is so fat with ad pages — including eight advertorials, running a total of 78 pages — that getting to its content is like fighting one’s way through the canebrakes along the lower Rio Grande.

The issue describes Texas through memories of childhood and adolescence, and that’s a relief from the usual definitions: Texas as a cluster of Metropolitan Statistical Areas, or markets, and Texas as a collection of electoral districts, a la Texas Tribune. Sadly, of the 10 shorter pieces in the front of the magazine, in sections entitled “Growing Up,” and “Leaving,” six come from people in the environs of New York City. Those contributors are mainly writers who, because the project of Texas publishing was betrayed, have made their careers in the American industry’s hometown. But even expatriate accounts tell us what Texas is like.

The traditional answer to the question, “What Is Texas?,” as founding writers at the Monthly often noted, was to be found in the pages of Texas Highways: nice people doing nice things, especially in county seats. Though some of the same Pollyanna approach is evident in the “Where I’m From” issue, a few of its accounts get closer to the truth, as I see it, anyway.

My observation has been that, when they are sincere, all thoughtful Texans voice a love-hate relationship with their setting, just as people in Northern Mexico do. The state’s turbulent history and even its terrains, like those of Northern Mexico, don’t offer us much choice: Texas is not Maine or Costa Rica or California North.

By that standard, the prize contribution in the “From” issue is an as-told-to piece from Rick Perry, his recollection of his upbringing on a dry-land North Texas cotton farm. Perry told interviewer Silverstein things like:

[The area around Haskell] could be one of the most beautiful places or it could be one of the most desolate, brutal, uninviting and uninspiring places … I spent a lot of time just alone with my dog. A lot.

Perry talks about daylight darkness created by dust storms, about bathing in No. 2 tubs, and, as John Kelso has noted in an Austin American-Statesman send-up, mother-made underwear. His tale is truly worth telling as fiction — in a novel by the likes of Cormack McCarthy.

On the other hand, in an interview with Monthly long-timer Mimi Swartz, Democrat Bill White talks in middle-class truisms, Texas Highways style.

The view of Texas as a locale not merely of nostalgia, but also as a problem or project leaps out, too, with contributions of El Paso historian David Dorado Romo, who finds commonalities in the Texas-Mexico and Israeli-Palestinian borders, and of Erykah Badu, who reports that “…in the late eighties crack cocaine came and everything went to hell” in the South Dallas neighborhood of her childhood.

For Perry, the question “what was Texas” does not draw an idyllic answer, and for both Romo and Badu, what’s relevant is not only “what was Texas?” but “what is it becoming?” That worry should torment both the Monthly and the 25-to-40 demographic in the issues to follow “Where I’m From.”

[A native Texan, Dick J. Reavis is an award-winning journalist, educator, and author who teaches journalism at North Carolina State University. He is a former staffer at the Moore County News, The Texas Observer, Texas Monthly, the San Antonio Light, the Dallas Observer, Texas Parks & Wildlife Magazine, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram and the San Antonio Express-News. He also wrote for The Rag in Austin in the Sixties. His latest book is Catching Out: The Secret World of Day Laborers.]