An interview with Nancy Kurshan:

From Yippie street protest to

fighting the American prison behemoth

“The prisoner usually has no idea how long he or she will be there… The rules for exiting are unclear at best and impossible to comprehend at worst. I believe that control unit prisons are tantamount to torture and an abuse of state power.” — Nancy Kurshan

By Jonah Raskin | The Rag Blog | February 28, 2013

Nancy Kurshan will be joined by fellow Yippie founder, Judy Gumbo Albert, as Thorne Dreyer’s guest on Rag Radio, Friday, April 12, 2013, from 2-3 p.m., on KOOP 91.7-FM in Austin, and streamed live on the Internet. Also, please see Judy Gumbo Albert’s photo essay, “Visiting Viet Nam, 1970-2013,” published this week in The Rag Blog. Nancy and Judy recently returned from a trip to Viet Nam.

If someone asked me to describe Nancy Kurshan in a word, the word I would choose would be “fearless.”

Kurshan, now 69, and a founding member of the Yippies — was born in Brooklyn, New York, and raised by Old Left parents. She has been an activist since high school days. Not surprisingly, she doesn’t like prisons any more than anyone else I know, though she enters prisons almost routinely. You might well say that she’s leery about them. Indeed, she knows how antithetical they are to the very essence of the human condition, and yet how thoroughly they define the human condition. That’s what might be called the prison paradox.

If you’re reading these words in The Rag Blog you probably know that prisons are almost everywhere on the face of the earth. You may remember that zealous Puritan settlers constructed them when they arrived in America in the seventeenth century. “The founders of a new colony,” Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote in his 1850 novel, The Scarlet Letter,“ have invariably recognized it among their earliest practical necessities to allot a portion of the virgin soil as a cemetery and another portion as the site of a prison.”

Graveyards and jails, cemeteries and prisons invariably go together.

Over the past 400 years or so, Americans have never stopped building prisons and American prisons, such as San Quentin, Alcatraz, and Angola in Louisiana, are world famous because of the books and movies about them and because of the harrowing testimonies by prisoners themselves.

Ask Nancy Kurshan. She has the facts and the figures. She’ll tell you all about America and its prisons. No one builds prison better than Americans, she says. No one builds more prisons than Americans, and no one builds the new generation of prisons, often called “control units,” with the same gusto as Americans.

When I asked her recently about her own prison experiences, she told me that she once spent 24-hours behind bars in Chicago and that “it drove me crazy.” Kurshan has been arrested so many times — at least 15 times by her own count — that they tend to blur in memory, though she remembers the incarcerations that followed street protests in the 1980s: the occupation of a Marine Corps office on International Women’s Day; a sit-in in the street that blocked traffic around the Federal Building in Chicago; yet another protest when she and others chained themselves to an African consulate.

|

| Image grab from the Marion Daily Republican, Marion, IL, April 28, 1989. Image from Freedom Archives. |

Kurshan has never allowed her own personal feelings about prisons to prevent her from protesting in the streets. And she has never allowed fear to stop her from aiming to dismantle the American prison behemoth that has grown bigger, meaner, and more vicious over the past several decades. A sense of boundless optimism carries her over immense hurdles.

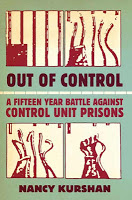

Kurshan describes her work — you can’t really call it “prison reform” — in a new book entitled Out of Control: A Fifteen Year Battle Against Control Unit Prisons that’s published by the Freedom Archives in San Francisco, and that has a trenchant introduction by Sundiata Acoli, who is currently “serving time” at the Federal Correctional Institution in Cumberland, Maryland.

I realize that “serving time” is probably not the most effective phrase for me to use here. As American Indian Movement activist and long time federal prisoner, Leonard Peltier, once said, “a prisoner doesn’t do the time. Time does the prisoner.”

Readers can order Kurshan’s informative, energizing book here, and you can learn more about it online at the Freedom Archives.

In the preface to the book, Kurshan says that, “In the end we lost every large issue we pursued.” But she’s not discouraged. She explains that her book “tells the story of one long determined fight against the core of the greatest military empire that has ever existed on this planet.” She adds, “If activists who stand in opposition to what Malcolm X called the ‘American nightmare’ can benefit from reading this and can move ahead with greater insight and effectiveness, then it will be worth while.”

Kurshan ends her preface with a quotation from the African revolutionary, Amilcar Cabral, who insisted, “Tell no lies, claim no easy victories.”

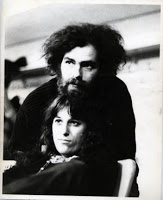

In this interview for The Rag Blog, Kurshan describes her political work and her thinking about prisons and prisoners. She also looks at her experience as a Yippie when one might say that she was a sweetheart of the Sixties. Her name and the name Jerry Rubin were nearly synonymous at the time of the Democratic National Convention in 1968 and at the Chicago Conspiracy Trial in 1969 and 1970. Rubin memorialized Kurshan in Do It!: Scenarios of the Revolution. Now as then her Yippie heart beats strongly.

This interview was conducted soon after Kurshan returned from a 2013 visit to Vietnam 40 years after the signing of the Paris Peace Accord that ended U.S. military presence there. To say that she was “high” would probably be an understatement.

|

| Nancy Kurshan in 2008. Image from TimeOut Chicago. |

Jonah Raskin: Aren’t all prisons “control unit prisons”?

Nancy Kurshan: There are at least two ways to answer your question — by the way, they go by various names: Secure Housing Unit (SHU), Administrative Maximum Facility (ADX), Supermax, and more. And remember there are variations from prison to prison. Still, a “control unit prison” is one in which all prisoners are locked in individual 9’ by 9’ boxes about 23 hours a day under severe sensory deprivation.

No fresh air. No natural light. The prisoner eats, sleeps, and defecates in a windowless cell. Meals come through a slot in the door. In some cases, the prisoner may be out of the cell for solitary exercise, but in other cases the exercise area is attached to the cell itself. There is restricted, or no, access to education and recreational facilities.

How are they different from “normal” prisons?

In most penal institutions, prisoners are in the “general population.” They live among other prisoners, take their meals in a social setting, have visitors (sometimes even conjugal visits), and participate in recreational activities with others. Some prisons offer education and training for jobs, though that’s becoming increasingly rare. A particular prisoner might be placed in solitary confinement as punishment — “thrown in the hole” in prison vernacular. The entire wing of a prison might also be “locked down” after an incident.

Is it a question of the degree of harshness and punishment?

All prisons are grim. Nonetheless, a control unit prison is qualitatively different than the rest. Control units limit the prisoner’s connection, not just with other prisoners, but also with family and friends in the outside world. Often only family members can visit and then only if approved.

The number and length of visits are limited, and no physical contact is permitted between prisoner and visitor. Visiting takes place over a Plexiglas wall and through telephones monitored by guards. Prisoners are searched before and after visits. They undergo body cavity searches and are often brought in shackles.

Sounds like psychological warfare and brainwashing.

It’s an endless hell — a living Kafkaesque limbo. The purpose of the control unit prison is to make the person feel helpless, powerless, and totally dependent on the authorities. A control unit institutionalizes solitary confinement as a way to exert maximum control over as much of the prisoner’s life as possible. This is long-term, severe behavior modification, and it’s the vilest, most mind- and spirit-deforming use of solitary confinement imaginable.

The control unit prisons probably cast a long shadow on everyone in prison, and perhaps on the whole society.

Control units have the affect of controlling prisoners in the general population. They’re meant to terrify prisoners so that they tolerate intolerable conditions. The federal prison at Marion, Illinois — and the word “Marion” itself — was meant to strike fear into the hearts of prisoners throughout the whole federal prison system.

|

| Nancy with son, Michael Kurshan-Emmer, wearing a Sundiata Acoli t-shirt, at 1998 Washington, D.C., march to free political prisoners. Image from Freedom Archives. |

Can you say more about the Kafkaesque aspect?

Inside a control unit, the prisoner usually has no idea how long he or she will be there. It’s an indeterminate sentence and the rules or guidelines for exiting it are unclear at best and impossible to comprehend at worst. I believe that control unit prisons are tantamount to torture and an abuse of state power.

Amnesty International recently released its 2012 report, “The Edge of Endurance: Conditions in California’s Security Housing Units,” in which the conditions in two California prisons — Corcoran and Pelican Bay — are described as “cruel, degrading and inhuman” and a violation of international standards. Readers can check it out at the Amnesty International site.

Are there political prisoners in the American penal system?

Absolutely. Let me name a few: Sundiata Acoli, who was one of the Panther 21 in the 1970s; Oscar Lopez Rivera, a Puerto Rican patriot; and Native American Leonard Peltier. They have all been imprisoned for over 30 years each! By comparison, Nelson Mandela, the world’s iconic political prisoner, spent 27 years in prison.

I recently traveled to Vietnam to participate in the celebration of the 40th anniversary of the Paris Peace Accords and met with people who were political prisoners in the Tiger Cages of the U.S.-backed South Vietnamese government. Their situations were nearly identical to those of political prisoners in this country today. Leonard Peltier, Sundiata Acoli, and Oscar Lopez Rivera are probably the longest-held political prisoners in the world.

Albert Woodfox* has been in prison at Angola for more than 40 years. Warden Burl Cain, said he would never transfer Woodfox out of solitary because, as he explained, “He is still trying to practice Black Pantherism, and I still would not want him walking around my prison because he would organize the young new inmates. I would have me all kinds of problems.”

What makes for a political prisoner? I ask because I often find it easier to recognize political prisoners in other parts of the world — Ireland, Russia, and China — than in the United States. I know individuals in the U.S. who began as conscious reformers and avowed revolutionaries and veered into crime — theft, robbery, dealing illicit drugs, and more.

People have been arguing about the nuances of this for years, but generally speaking a political prisoner is someone who is imprisoned for his or her participation in political activity.

Why do you think that you chose to work with prisoners, to secure their release, and to protect them from the worse abuses of the prison system?

Once I was in prison — as a result of my participation in the movements of the 1960s and 1970s — it was difficult to turn away. At first, there were many amazing political prisoners that grabbed my attention. I felt that if our movement were to succeed, we could not abandon people behind bars. If we did, we couldn’t hope to move forward.

Once I was in prison — as a result of my participation in the movements of the 1960s and 1970s — it was difficult to turn away. At first, there were many amazing political prisoners that grabbed my attention. I felt that if our movement were to succeed, we could not abandon people behind bars. If we did, we couldn’t hope to move forward.

Imprisonment was chilling for everyone — on the outside as well as the inside. To a large extent, Americans are afraid of prisons and political prisoners. I didn’t want to be one of them.

What did you learn as you became more involved?

That prisons are about racism and the social control of people of color. I felt that the work I was doing was an important way to be a principled anti-racist. It was also a way for me to express moral outrage about the fact that humans are treated worse than animals, though I don’t wish those same conditions on animals either.

When were you arrested and jailed in the 1960s and 1970s?

More times than I can remember. The first time was in 1967 for mass civil disobedience at the Pentagon. In 1971, I was arrested on the campus of Kent State for spray-painting the words “U.S. Out Of Laos.” I was charged with a felony — malicious destruction of property with damage over $100 — and told that they would break it down to a misdemeanor if I agreed to leave Kent, Ohio.

By then, I was happy to go. Our house had received bomb threats. Then, in the 1980s, I was part of a women’s group called “No Pasaran” and was arrested protesting U.S. wars in Central America. Most of the charges are not memorable. As I recall, they were for “disturbing the peace.” I got off completely, or had to pay a fine after pleading guilty.

What do you remember about your own jail time?

The Pentagon jail time, my first, was in what I call “white peoples’ jail.” There were about a thousand of us. The authorities created a men’s dormitory and a women’s dormitory. Ours was lined with hundreds of cots; I was there with Anita Hoffman. We stayed overnight, went to court, pled no contest, paid $25, and left. In Chicago in the 1980s, it was rougher. We were held at the lockup at 11th and State, like all other detainees, and single-celled with nothing to read and nothing but a bologna sandwich to eat.

We could talk to people across the cell, but I remember being cold and uncomfortable, lying on a cement bed. The guards were unresponsive to requests. You could call out to your heart’s content and they wouldn’t come. The longest time I spent there was about 24 hours and it drove me crazy. I can’t imagine what long-term solitary must feel like.

How do you feel about the Yippies now, looking back?

|

| Nancy Kurshan and Jerry Rubin. |

I love the Yippies! We were really onto something and reached many more people than we’re given credit for. Most Left history is written by people who were in what we considered the “straight Left.” They were not fond of us then and they still aren’t.

Our use of the media, creation of myths, comedy, and appeal to artists was fabulous. We levitated the Pentagon to allow the evil spirits to flee (clearly not high enough), ran a pig for President, and burned money at the Stock Exchange on Wall Street.

We also represented a segment of American youth that was in militant rebellion. We didn’t lead them. We were a part of them and we were not part of any official Left organization. Much of the Left dismissed the youth population. They criticized us for alienating older, middle class people. I think the youth movement was a vital engine of the anti-war movement, driving everything and everyone to the Left and forcing debate onto dinner tables.

Any criticisms?

My main issue, of course, is the sexism of the Yippies. But honestly, it was no worse than in the rest of the Left. Sexism was an Achilles Heel of the whole movement.

The Yippies seemed to me to be about couples — you and Jerry Rubin, Judy Gumbo and Stew Albert, Anita and Abbie Hoffman. What thoughts do you have now about sex and gender and power in the Yippie universe?

Yippies weren’t any more about couples than the rest of the movement. Male supremacy was “normal.” I had been a political activist beginning in high school; then in the 1960s and 1970s my role in the movement was compromised. At times, I went to work every day so that Jerry Rubin and the guys who were living at our tiny apartment could be movement activists!

After work I shopped. Then I came home and cooked. Then the men treated us like gophers and we accepted it. It was hard to find one’s own voice and it was easy to “stand by your man” when conflicts arose. Until the women’s movement burst on the scene, there were awkward distances between women.

When Robin Morgan quit the Yippies and published “Goodbye To All That” in the underground paper, RAT, I was uncomfortable. I knew she was right about the big picture, if not everything. It was embarrassing and I didn’t know what to do. Change can be confusing and uncomfortable. Morgan’s piece and my 1970 trip to Vietnam really pushed me to fight male dominance and find my own voice.

To get back to prisons. In what ways have they changed over the last decades?

Two things strike me. One is the massive incarceration of people of color. In 1994, for instance, there were 85,000 people in federal prisons. Today. there are 218,000. In state and federal prisons there are 2.3 million people behind bars. We are the “Incarceration Nation.”

Albert Hunt stated in The New York Times (November, 20, 2011) that, “With just a little more than four percent of the world’s population, the U.S. accounts for a quarter of the planet’s prisoners and has more inmates than the leading 35 European countries combined.”

Prisons overflow disproportionately with black and Latino prisoners. According to the same New York Times article, “more than 60 percent of the United States’ prisoners are black or Hispanic, though these groups comprise less than 30 percent of the population.” One in every nine black children has a parent in jail!

What are the other trends?

The prison system has become much more punitive. When we began our work in the 1980s, Marion Federal Prison was the only control unit prison in the federal and the state system. When we argued they should shut it down, they argued that it would allow the rest of the system to function more effectively. We said no, it would function as an anchor and pull the whole system in the direction of tighter control. We would have liked to have been proven wrong, but unfortunately we’ve been proved right. Now, virtually every state has at least one control unit prison.

Is there hope?

Just recently there has been some motion. Two serious challenges have developed. One, that this form of imprisonment is too expensive. Our whole society is running out of money, thanks in part to our bloated military. Also, in some states, like California, prisoners have stood up by the thousands and said, “We won’t take it no more.”

There have been hunger strikes of 6,000 or more prisoners. Support on the outside has helped give voice to grievances. In response to hunger strikers at Pelican Bay, The New York Times, in an editorial on February 8, 2011, entitled “Cruel Isolation,” said, “For many decades, the civilized world has recognized prolonged isolation of prisoners in cruel conditions to be inhumane, even torture. The Geneva Convention forbids it.”

Is anyone rehabilitated through the effort of prison programs?

As Malcolm X said, “I ain’t never been habilitated, how can I be rehabilitated?” Sure, some people have come out of prison wiser than when they went in, or perhaps with some skills they didn’t have. But by and large, the problems are structural, not individual and have to do with whether or not society has room for ex-prisoners. Generally, when people get out of prison, no matter how good they are, their options are lousy. They face great obstacles.

The Russian novelist, Fyodor Dostoevsky, shrewdly observed 150 years or so ago that, “The degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons.” When you enter a prison what are some of the first things you hear, see, and feel?

|

| Nancy in Hanoi, 2013, with Agent Orange victims. |

That Dostoevsky quote has always been a favorite of mine. When I enter a prison, I usually feel I’m entering a bastion of the military. There are gun towers, barbed wire, metal detectors, arbitrary rules, regulations, and tight surveillance. Then there are the pat-downs.

The first thing that comes to mind is that I’m on a slave ship — a landlocked slave ship. The racial aspect is undeniable, from the waiting room to the visiting room. After all these years, you would think I would be used to it, but I’m not. For me there is no experience like it.

What degree of civilization would you say exists in the U.S.?

I would answer with a shrewd quote from Gandhi. When he was asked what he thought of Western civilization, he replied, “That would be a good idea.” I’ve just returned from Vietnam, still a primarily agrarian, developing country. They have one of the lowest imprisonment rates in the world. Vietnam is a more civilized place than the U.S.

Since you’re just back from Vietnam would you give us your impressions of the country?

Vietnam is beautiful and vibrant with more than half the population under 20. The legacy of the war is still enormous. More bombs were dropped on Vietnam than on all of Europe in World War II. We visited the Highway 9 Cemetery of the Fallen Combatants where thousands of Vietnamese are buried. As I looked at the tombstones I noticed how very many were cut down in their youth. Somewhere between 2 and 4 million people were killed in the “American War” — as the Vietnamese call it.

You met people and talked face-to-face?

Nearly everyone had a story to tell about their family’s sacrifice, although they tell it after persistent prodding. We visited schools where children are suffering from severe birth defects as a result of the millions of gallons of herbicides such as Agent Orange that the U.S. used. These children are three generations removed from direct exposure!

We also went to what was the Da Nang Air Base during the war (now a regular airport) where the U.S. is just now beginning cleanup, 40 years later. That’s a drop in the bucket because it’s only one “hot spot” and to the tune of $43 million which is really nothing.

The country seems to have taken your breath away.

The experience was fabulous: the natural beauty and the energy and warmth of the people; the privilege to share in the celebrations of the Paris Peace Accords; the meeting with Madame Binh and many people who survived the Tiger Cages. I went inside the underground “Cu Chi tunnels” that testify to the ingenuity and determination of the Vietnamese to be free from of colonialism. Seeing the legacy of the war made me angry. I’m still processing my time in Vietnam.

[Jonah Raskin, a regular contributor to The Rag Blog, is a professor emeritus at Sonoma State University and the editor of The Radical Jack London: Writings on War and Revolution. Read more articles by Jonah Raskin on The Rag Blog.]

*UPDATE: As we went to press a federal judge ordered the release of former Black Panther and member of the Angola 3, Albert Woodfox. This is the third time Woodfox’s conviction has been overturned in a federal court, but prosecutors successfully reversed the two previous court decisions and are expected to try once more to keep Woodfox behind bars.

Thank you for this interview with Nancy. I admire her commitment and courage.