To Kill a Mockingbird turns 50:

Harper Lee’s muddleheaded

Novel for white liberals

By Jonah Raskin / The Rag Blog / July 13, 2010

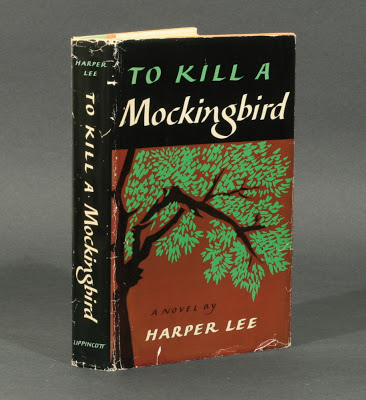

This summer, literate Americans are feting the 50th anniversary of the publication of Harper Lee’s one and only novel, To Kill a Mockingbird, which was originally published in 1960, at the start of the civil rights movement of the 1960’s. It went on to become a trendy Hollywood movie with Gregory Peck as Atticus, the lawyer who defends a black man named Tom Robinson, and, according to legend, inspired many young Americans to go to law school hoping to follow in his footsteps.

I suppose I ought not to be a killjoy and should refrain from ridiculing the novel and its faithful readers. I suppose I ought to be grateful that novels are still read and that readers get excited about the characters they meet in the pages of fiction. I certainly wouldn’t want to stop anyone from reading the novel.

But I think that Americans might read it with far more sensitivity than they have shown so far this year, and certainly with more sensitivity than Mary McDonagh Murphy shows in her new book about Lee’s novel that’s entitled Scout, Atticus, and Boo – after three of the novel’s main characters. Murphy has been on NPR gushing about To Kill a Mockingbird, and listeners have called in to say how much they love the book and its characters, so let’s get them straight before tackling other matters.

Scout, of course, is Atticus’s young daughter who has a habit of crawling into her father’s lap and then “hiding in his lap” with his arms around her, though curiously no one in the novel comments on that peculiar habit of hers, nor does the author. Is there some kind of unspoken sexual attraction between daughter and father. One would think so, though Lee doesn’t go there.

The third character whose name appears in the title is Boo, the mysterious man who lives next door to Atticus and to Scout, and a stock figure from the pages of Gothic fiction. Boo plays a major part in the very hokey ending of the novel, as hokey an ending as any in American literature and reason enough to disbelieve Oprah Winfrey who has called To Kill a Mockingbird “our national novel.” It is undoubtedly a popular novel — it’s one of the books in The Big Read program sponsored by the National Endowment for the Arts — but I truly hope it isn’t the novel that Winfrey wants it to be.

To Kill a Mockingbird has long troubled me — beginning with the title itself. I never much cared for the mockingbird as a symbol either. “Mockingbirds don’t do one thing but sing their hearts out for us,” one of the novel’s minor characters explains to Scout. “That’s why it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird.” Almost all novels that are assigned to high school and college students have to have at least one symbol so that teachers can invite the students to hunt for the symbol or symbols, and then to write a paper in which they explain what the symbols means. Lee fulfilled her part of the bargain.

The mockingbird symbol and the hokey ending aside, the main reason that the novel raises my hackles is that it’s besotted with white Southern liberalism. It’s a novel that is meant to make liberals feel good about themselves. It pats them on the back and says in so many words, “you’ve done all you could do about race and racial issues.” It does this largely through Atticus, who has good intentions, but who is naïve and muddleheaded, as when he says that the KKK is “gone” and that “it’ll never come back.” He doesn’t know what he’s talking about.

To Kill a Mockingbird is set in 1935; surely Harper Lee knew that the KKK was alive and well in the 1930’s and that it had a great deal of life left in it afterward. She might have used the benefit of hindsight. Indeed, the KKK reared up its ugly racist head in the 1960’s when it boasted 17,000 members.

Lee is wrong about a lot of the history that shows up in To Kill a Mockingbird. About one of her ancestors, Scout says that he “bought three slaves and with their aid established a homestead” — making it sound like slavery was fun for everyone. She calls the Civil War “a disturbance.” Reconstruction is described as an era that brought “economic ruin” to the South — as though slavery never did.

The novel’s depiction of the 1930’s is superficial to say the least. Of course, the single most important trial in the South in the 1930’s was the trial of nine young African American men known as the “Scottsboro Boys” who were charged in 1931 with gang raping two white women, and who were found guilty by an all-white jury and sentenced to die in the electric chair.

The most notable lawyer connected to the case was Samuel Liebowitz, a New York Jewish lawyer, who was the target of a great deal of anti-Semitism. No white Southern lawyer — no Atticus — rushed to the defense of the young men, aged 13 to 21, who were on trial in a courtroom that was a mockery of justice. Atticus knows nothing about that case, nor does he know anything about the seamy side of the American legal system. “In our courts all men are created equal,” he says. Tell that to the Scottsboro defendants who went on trial again and again for six years.

Tom Robinson, the African American who is on trial in To Kill a Mockingbird, is a cliché, and so are all the African American characters in the novel including Calpurnia, the cook who practices “voo-doo” and whom Scout chides for talking “nigger talk.” Most of the African American characters are in the background; more often than not they’re to be heard “laughing in the night.”

Robinson has a shriveled hand, and Lee observes, “If he had been whole he would have been a fine specimen of a man.” Why he couldn’t be a “whole man” is puzzling. All the other characters in the book are “whole.” Making the one African American male less than whole seems unfair and even mean-spirited, and it seems unfair too that he’s shot and killed near the end of the novel. White liberals get their cake and eat it too.

Atticus defends Robinson out of the goodness of his heart, and then Robinson foolishly tries to escape from prison and dies in the attempt. There’s one less ornery African American in the world to worry about or to defend in court.

Morals and sermons come fast and furious in the novel — from Lee herself, from Atticus, and from Scout’s teacher who compares the U. S. with Nazi Germany. “We are a democracy,” she tells the students. “That’s the difference between America and Germany. We are a democracy and Germany is a dictatorship.”

That’s exactly what liberals wanted to hear in the 1930’s and again in the 1960’s. To Kill a Mockingbird is the perfect novel about race for the Kennedy Camelot years, though the 1960’s would soon explode most of the liberal myths about race. I suppose white liberals of today need assuring myths once again, as our prisons bulge with African Americans, and as poverty and drugs make war on African Americans.

Scout’s teacher talks about democracy, but there is nothing that’s democratic about the southern society that’s depicted in To Kill a Mockingbird. Read it carefully and it’s obvious that the good old Southern boys — Atticus and the sheriff — are in control and determine not only the law but reality for the citizens in the town. Their word is law.

Yes, the novel has a mean Southern racist named Bob Ewell who dies for his sins, but his punishment is far closer to a lynching than a fair trial. A liberal might call his death poetic justice, but there’s nothing just about it. Harper Lee sweeps, right under the carpet, not only Ewell’s fate, but almost all of the racial complexities that her novel raises.

I hope that Oprah Winfrey is wrong about To Kill a Mockingbird, as wrong she has been about so many other books she has touted on TV. Is there a “national novel” as she claims? Probably not! Though there are national novels — plural. While white liberals are busy celebrating the 50th anniversary of Lee’s Gothic Southern novel, the rest of us might read or reread that classic of crime and punishment, Native Son, which was published 70 years ago in 1940, and that was written by the great African American novelist, Richard Wright, who died in 1960, the same year that To Kill a Mockingbird was published.

Native Son was a best seller too, and a slap in the face of white liberals. It might wake up America today.

[Jonah Raskin is the author of The Mythology of Imperialism and a professor of communications and literature at Sonoma State University.]

The Rag Blog

I was 22 when I read To Kill a Mockingbird. I had killed a lot of mockingbirds by that time. I have killed a hell of a lot since. They whistle outside your bedroom window at four in the morning in the summer, asking to be shot. But, getting back to the book. Before I read TKaMB at age 22 I had already read Truman Capote, Erwin Shaw and Norman Mailer. Compared to their work the book was ho-hum and

My mother and I saw the movie together in 1960, when I was 13, a rare mother-daughter night out for the busy mother of 4-soon-to-be-5; Mom was pregnant with my youngest bro.

She clearly thought it an important movie (I honestly don’t remember if we’d rewad the book first; I know I have read it)and wanted me to see it because she MADE THE TIME for us to see it, at a theater, together. Even though Mom was no activist, she knew that black people are human beings and should be treated as human beings, and that the same applies to reclusive, “eccentric” folks such as Boo Radley, a pivotal figure in Lee’s work.

While it’s easy to look back 50 years and say ‘oh pish tush’ to that message, in 1960 in Ft. Worth Texas, it was an unmistakable breath of radical liberation theology.

btw, at 13, I had already read Shakespeare, all the dirty parts of the Bible, and J Edgar Hoover’s “The Naked Communist” (hoping it would be racy), as well as many “grown-up” novels of the day. No doubt, if I read them again, I would find many of the books that once interested me peurile and lame. Books are only required, however, to change your consciousness once in order to be significant.

TKAM was arousing in its day; better books and movies have since delivered the same message more relevantly to their cultural milieu and hopefully will continue to do so.

Raskin should look up the term irony, as Lee uses it throughout as a tool to describe the horrors of southern racism. The school teacher, for example, tries to show the difference between Germany and the US in the 30s and the irony is thick as butter.

Lee’s attempt was not to make liberals feel better but to create more of them. She did.

And the civil rights movement did not start in the 60s but rather just after WW II and was going full throttle in the late 50s.

raskin’s superiority is super superior!

I’d like to think this article was actually an attempt to prod readers to actually read (or re-read TKAM). Otherwise, it comes off as mean-spirited political rant rather than a scholarly attempt at literary criticism.

It’s just a movie. Movies are made to make money.

While it may be true the movie did not tell the whole story of social and cultural prejudice, we are not without all manner of contemporary playwrights who endeavor to correct that single flaw.

Marian Wizard made the essential point in this discussion. As a proud radical, I’d say TKAM reached a lot of white people, northern as well as southern, in a day and time when they might not have been otherwise reached.

We could quite easily put Cry the Beloved Country in the same category.

As for the liberals, they’re inscrutable anyway. Who can say what makes them feel good about themselves or not? –I doubt even they can.

I love the photo posted with this story: as I’ve said on my Facebook page, perhaps the greatest charge to hold against Harper Lee is that she accepted an award from George W(ar Criminal). Bush.

“Scout’s teacher talks about democracy, but there is nothing that’s democratic about the southern society that’s depicted in To Kill a Mockingbird. Read it carefully and it’s obvious that the good old Southern boys — Atticus and the sheriff — are in control and determine not only the law but reality for the citizens in the town. Their word is law.”

I think Jonah Raskin missed the entire lesson of the book. Lee wrote this to show irony.

Scout says that about her ancestors because she too is confused about slavery and doesn’t see it from a black person’s point of view.

Also, the novel was not written to make white liberals feel good about themselves. t may have, but it was clearly not written for that purpose. A college professor should have better reading comprehension skills.

I know I’m late to this party, but so is Raskin. The Wall Street Journal just had a piece attacking TKaM last month. Their argument was that it’s too simple, his that… well, I guess that he can’t identify sarcasm and therefore thinks Lee is glossing over the horrors of Southern racism, the Civil War, etc. I guess that’s why she wrote a book where Tom Robinson got off, the KKK didn’t exist, the heros were all liberals and Northerners, and Atticus Finch had a huge courtroom victory… oh, wait.

I wonder, does Raskin really not understand the way Scout’s narrative voice uses irony, or does he identify it as “liberal” (whatever that means to him) and then dismisses it for that reason?

As for the WSJ’s critique, here’s my rebuttal. http://unapologetic-conjecture.blogspot.com/2010/06/case-of-wall-street-journal-vs-to-kill.html

I, and most leftists, especially those about six of us still left from the 1960s (including the now freed Marilyn Buck), can appreciate the critique by Mr. Raskin. However, he has the advantage of 50 years of improving political consciousness on the question of race in America, formally anyway. At the time the book , and later the movie, had a powerful effect, if for no other reason that they were (and are) good literature and cinema. Beyond that, as literary critic and great Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky noted, one cannot reasonably go. The other stuff, the political fight for black liberation in “real time” stuff, was (and is) up to us-forward in the black liberation struggle.

Note: Needless to say any two pages of Richard Wright’s Black Boy or Native Son or any of James Baldwin’s work, especially The Fire Next Time has more truth about the racial core of American society than all of Lee’s book. But that is a different non-literary question.