United States global hegemony is coming to an end.

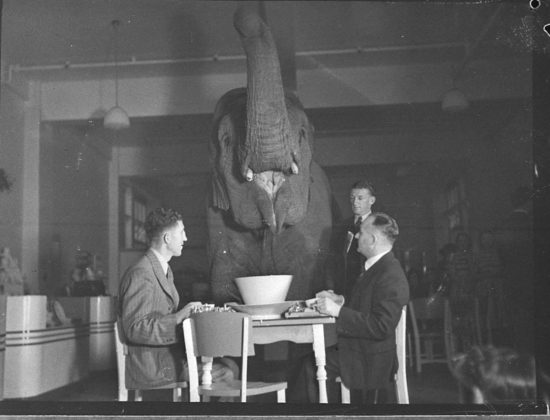

Elephant in the room. Photo by Sam Hood, March 24, 1939. From the

collection of the State Library of New South Wales..

[This article was adapted by the author from a 2017 post that appeared in The Rag Blog.]

An empire in decline

United States global hegemony is coming to an end. The United States was the country that collaborated with the Soviet Union to defeat fascism in Europe and with Great Britain to crush Japanese militarism in Asia in 1945. The Soviet Union, the first Socialist state, suffered 27 million dead in the war to defeat the Nazis. Great Britain, the last great imperial power, was near the end of its global reach because of war and the rise of anti-colonial movements in Asia and Africa.

As the beneficiary of war-driven industrial growth and the development of a military-industrial complex unparalleled in world history, the United States was in a position in 1945 to construct a post-war international political and economic order based on huge banks and corporations. The United States created the international financial and trading system, imposed the dollar as the global currency, built military alliances to challenge the Socialist Bloc, and used its massive military might and capacity for economic penetration to infiltrate, subvert, and dominate most of the economic and political regimes across the globe.

The United States always faced resistance and was by virtue of its economic system and ideology drawn into perpetual wars, leading to trillions of dollars in military spending, the loss of hundreds of thousands of American lives, and the deaths of literally millions of people, mostly people of color, to maintain its empire.

A multipolar world is reemerging with challenges to traditional hegemony.

As was the case of prior empires, the United States empire is coming to an end. A multipolar world is reemerging with challenges to traditional hegemony coming from China, India, Russia, and the larger less developed countries such as Brazil, Argentina, South Africa, South Korea, and Thailand. By the 1970s, traditional allies in Europe and Japan had become economic competitors of the United States.

The United States throughout this period of change has remained the overwhelming military power, however, spending more on defense than the next seven countries combined. It remains the world’s economic giant even though growth in domestic product between 1980 and 2000 has been a third of its GDP growth from 1960 to 1980. Confronted with economic stagnation and declining profit rates the United States economy began in the 1970s to transition from a vibrant industrial base to financial speculation and the globalization of production.

The latest phase of capitalism, the era of neoliberal globalization, required massive shifts of surplus value from workers to bankers and the top 200 hundred corporations which by the 1980s controlled about one-third of all production. The instruments of consciousness, a handful of media conglomerates, have consolidated their control of most of what people read, see, hear, and learn about the world.

A policy centerpiece of the new era has been a massive shift of wealth from the many to the few.

A policy centerpiece of the new era, roughly spanning the rise to power of Ronald Reagan to today, including the eight years of the Obama Administration, has been a massive shift of wealth from the many to the few. A series of graphs published by the Economic Policy Institute in December 2016, showed that productivity, profits, and economic concentration had risen while real wages have declined, inequality increased, gaps between the earnings of people of color and women and white men grew, and persistent poverty remained for twenty percent of the US population. The austerity policies, the centerpiece of neoliberalism, spread all across the globe. That is what globalization has been about.

Contrary to the shifts toward a transnational capitalist system and the concentration of wealth and power on a global level, the decline of U.S. power, relative to other nation-states in the twenty-first century, has increased. China’s economy and scientific/technological base have expanded dramatically. The wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, and the spreading violence throughout the Middle East have overwhelmed U.S. efforts to control events. Russia, Iran, China, and even weaker nations in the United Nations Security Council have begun to challenge U.S. power and authority. Mass movements increasingly mobilize against regimes supported by the United States virtually everywhere (including mass mobilizations within the U.S. as well).

However, most U.S. politicians still articulate the mantra of “the United States as the indispensable nation.” The articulation of American Exceptionalism represents an effort to maintain a global hegemony that no longer exists and a rationale to justify the massive military-industrial complex which fuels much of the United States economy.

Imperial decline and domestic Politics

The narrative above is of necessity brief and oversimplified but provides a backdrop for reflecting on the substantial shifts in American politics. The argument here is that foreign policy and international political economy are “the elephants in the room” as we reflect on the outcomes of recent elections. It does not replace other explanations or “causes” of election results but supplements them.

The pursuit of austerity policies has been a central feature of international economics.

First, the pursuit of austerity policies, particularly in other countries (the cornerstone of neoliberal globalization) has been a central feature of international economics since the late 1970s. From the establishment of the debt system in the Global South, to “shock therapy” in countries as varied as Bolivia and the former Socialist Bloc, to European bank demands on Greece, Spain, Portugal, and Ireland, to Reaganomics and the promotion of Clinton’s “market democracies,” and the Obama era Trans-Pacific Partnership, the wealth of the world has been shifting from the poor and working classes to the rich.

Second, to promote neoliberal globalization, the United States has constructed by far the world’s largest war machine. With growing opposition to U.S. militarism around the world, policy has shifted in recent years from “boots on the ground,” (although there still are many), to special ops, private contractors, drones, cyberwar, spying, and “quiet coups,” such as in Brazil and Venezuela, to achieve neoliberal advances.

One group of foreign policy insiders, the humanitarian interventionists, has lobbied for varied forms of intervention to promote “human rights, democratization, and markets.” 2016 candidate Hillary Clinton and a host of “deep state” insiders advocated for support of the military coup in Honduras, a NATO coalition effort to topple the regime in Libya, the expansion of troops in Afghanistan, even stronger support of Israel, funding and training anti-government rebels in Syria and the overthrow of the elected government of Ukraine. Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton was a major advocate for humanitarian interventionist policies in the Obama administration.

Humanitarian interventionists have joined forces with ‘neoconservatives’ in the new century.

Humanitarian interventionists have joined forces with “neoconservatives” in the new century to advocate policies that, they believe, would reverse the declining relative power of the United States. This coalition of foreign policy influentials has promoted a New Cold War against China and Russia and an Asian pivot to challenge an emerging multipolar world. The growing turmoil in the Middle East and the new rising powers in Eurasia also provide rationale for qualitative increases in military spending, enormous increases in research and development of new military technologies, and the reintroduction of ideologies that were current during the last century about mortal enemies and the inevitability of war.

The “elephant in the room” that pertains to U.S. politics, now that Afghanistan has “fallen” after 40 years of covert and overt military intervention, must include growing opposition to an activist United States economic/political/military role in the world, the long history of United States imperialism.

Finally, to the extent that economics affects domestic politics the neoliberal global agenda that has been enshrined in United States international economic policy since the 1970s, coupled with humanitarian interventionism, has had much to do with rising austerity, growing disparities of wealth and power, wage and income stagnation, and declining social safety nets at home. As millions of Americans struggle to survive poverty, inadequate access to healthcare, homelessness, a variety of environmental disasters it is time to include visions of a non-interventionist, anti-militaristic foreign policy back into our progressive political agenda.

[Harry Targ is Professor Emeritus at Purdue University. He taught United States foreign policy, international relations, and Peace Studies. Harry is a co-chair of the Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism (CCDS). He lives in West Lafayette, Indiana, and blogs at Diary of a Heartland Radical.]

Read more articles by Harry Targ on The Rag Blog and listen to Thorne Dreyer’s Rag Radio interviews with Targ.

On the “activist” US role (AKA imperialism), the following came to mind: From 1978 to 1991, I worked at Texas Instruments in Austin. One of the other technicians there was a middle-aged gentleman from Vietnam, old enough to have seen Ho in person. While his French was excellent (he studied in France during the French occupation), his English was still a bit rough, as he and his family, having sided with the South Vietnamese forces (primarily, I gathered, from dislike of what the North became as a result of increased Soviet influence; he liked Ho), had to leave in a hurry.

One day, walking down the aisle between workstations, I saw he had used graphics to create a Vietnamese flag on his monitor (we were then building the ill-fated TI PC). I stopped to talk, as there seemed to be something rather poignant in his gesture. I still recall what he said about the American approach to “nation building”: “America sends lots of guns and lots of money. You can’t build a country with guns and money.” (My memory, of course, may not have the exact words, but this was clearly the gist of it.)

Seems we just can’t learn, can we? Or various interests would prefer we not learn. And of course the irony of this conversation having taken place in the employ of a (then) major defense contractor…

But his point, I think, still stands: Guns and money will not build a nation. Including the nation handing out the guns and money.