There is little justice in the ‘criminal legal system’ for black people.

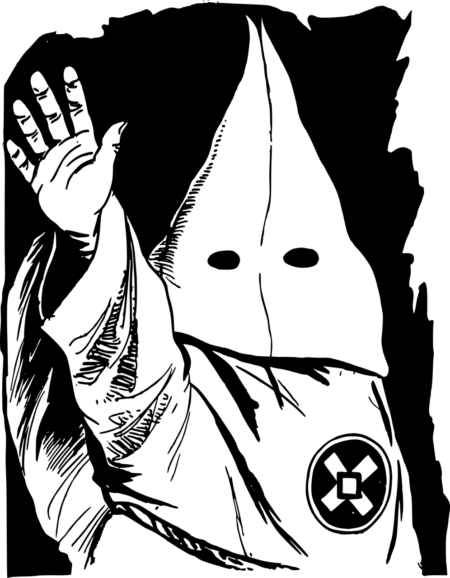

SAN MARCOS, TX — I lived in Vidor, Texas, until I was four years old, with my mother, grandparents, and an aunt and uncle. Two other aunts had just married and moved nearby. Vidor has a richly-deserved reputation for being one of the most inhospitable places in Texas for black people. In 1967, my friends Bill and Loretta Oliver and I took a 10-minute drive from the north side of Beaumont to Vidor to try to find the Ku Klux Klan headquarters we had heard about. Much to my surprise, it was housed on Main Street in the same storefront space where I had attended day care in 1948.

For reasons I can’t explain, none of that part of my family ever made racist or derogatory remarks toward black people that I remember. Maybe it was because of their brand of religion, or maybe they were just nice people.

After my mother remarried, we moved from Vidor to Port Arthur, where I lived until going off to college. I’ve thought about, written about, and observed racism all of my life, at least since the age of 10 when I began learning about the pervasiveness of racism in America from a black woman who did housekeeping, cooking, and child care for my parents, both of whom worked full-time jobs in the refineries.

At first, the racism I observed was stark

and easy to identify.

At first, the racism I observed was stark and easy to identify — blacks were consigned to seats in the back of city buses, could not eat in whites-only restaurants (which were the only ones I knew about), had separate water fountains from whites in stores and other public places, were denied public restrooms in the white-owned stores in which they could shop, were openly demeaned by racist jokes told by many whites, were not hired for many jobs. None of my public school teachers were black, black people still faced the threat of violence (or even death) by whites for any perceived slight or unacceptable behavior, and on and on.

Now, the racism is less obvious and more difficult to prove to everyone’s satisfaction. In most settings, it manifests itself more discreetly than it did 65 years ago, but it is just as real and as damaging as it ever was. Nowhere is racism more manifest today than in the treatment of blacks (and other minorities) by the police.

The most startling disparities can be found in the criminal legal system, a system that I worked in off and on for about 40 years. The data are there for anyone to find, if they want to find it. And my experiences in the legal system are consistent with those data. When my family and I were living in Bryan-College Station, I was appointed to represent an 18-year-old black teenager who was accused of capital murder in the death of a white man. His 17-year-old brother and a friend, who was also a teenager, were charged in the same murder.

One morning when we had a preliminary hearing scheduled, a prominent attorney was in the courtroom for proceedings before court began. He told the district attorney that he hoped “the niggers” got the needle (lethal injection). That statement became a part of our motion for a change of venue because the publicity and racial animus was so strong in Brazos County. Of course, the motion was denied.

All blacks native to this country were born into a world ‘where having a dark skin is a crime.’

I learned early that, to paraphrase a line in a Pete Seeger song about Huddie Ledbetter, all blacks native to this country were born into a world “where having a dark skin is a crime.” That’s a view that too many whites don’t understand or haven’t understood until recently.

The District Attorney in Brazos County didn’t recognize it. The District Judge who presided at the trial didn’t recognize it. The Sheriff didn’t recognize it. The Texas Rangers, who aided in the investigation, didn’t recognize it. I’m not sure my co-counsel recognized it, nor did the attorneys for my client’s co-defendants.

My client participated in a horrible crime — the unjustified killing of another human being, a person who had stopped to help when my client and his companions had car trouble on a cold night. The evidence left little room for doubt about my client’s participation in the crime, but the desire to put him to death for the killing of a white man was so strong that the state was willing to devote tens of thousands of dollars needed to conduct a three-month long jury trial, plus all the pretrial efforts made in the year preceding trial.

And after losing their case on appeal, the state came back to put my client on trial again for capital murder, though in a different county, with different defense attorneys, at further great expense to the county. This time, the verdict stood, and 12 years after the killing, my client was executed by lethal injection. A good thing that came from his life is that he willed his body to the University of Texas Medical School in Galveston to be used to teach med students.

The victims in the other cases were black or the perpetrator was white.

This is not an unusual story, especially for the South, but we found when we were preparing for trial that a half-dozen killings in Brazos County during the previous year that could have been prosecuted as capital murder cases were not. The difference between those cases and my client’s was that the victims in the other cases were black or the perpetrator was white.

For that reason, among others, I refer to the “criminal legal system,” rather than the “criminal justice system.” There is little justice in the criminal legal system for black people.

But it is not only injustice in the criminal legal system that is a problem. Try to imagine what it is like every day for a black person to live in a society where having dark skin is a crime, if not literally, metaphorically, in the ordinary activities of living: always having someone watching you in a store to make sure you don’t steal some product; observing that whites avoid getting too close to you or keep more than a common social distance; being fearful of driving at night or driving any time in an area where mostly whites carry out their lives; being terrified when your teenage child is out in a car; merely walking down the street; bird-watching in a public park; not allowing your 8-year old child to play with a toy gun. Breathing while black is an apt description, and it has to be exhausting.

Blacks are more likely to be targeted for criminal activity than whites.

My views of the police are informed by spending over seven years in two communities as a police legal adviser, as well as by litigating civil rights complaints against law enforcement on behalf of people of all colors. I have no doubt that blacks are more likely to be targeted for criminal activity than whites. Just look at the arrest data for drug-related crimes. Blacks use illegal drugs slightly less than whites, but they are arrested for drug-related offenses almost three times as often, and incarcerated for those offenses about five times as often. No doubt there are many reasons for these disparities, but chief among them is racism.

The writer Tiffanie Drayton, in a commentary in the New York Times in June, asked an important question and provided some answers:

Why was it so hard to have a good life as a black person in America?

I scanned history books for answers, only to find black pain, death and oppression. Slavery, black codes, lynching, Jim Crow, school segregation, redlining, drug wars, mass incarceration and gentrification. Assassinations, exiles, unending persecution. Black successes met with a storm of violence, like the surge of white supremacist hate after Reconstruction and even the election of Barack Obama.The unfair banking practices that prevented black homeownership in the suburbs and the gentrification that reclaimed black cities for white people. Images of lifeless black bodies, casualties of war: black men and women hanging from trees; Emmett Till’s battered face; Martin Luther King lying in a pool of blood, his face half-covered by a white cloth; Malcolm X, mouth agape, dead on a stretcher.

America denies so many black people basic security, freedom, and human dignity.

Drayton explains how she escaped the smothering racism of her youth and young adulthood:

The privilege of dual citizenship afforded me sanctuary in Trinidad and Tobago. As I settled here, my life slowly became colorful and vibrant again. I paraded through the streets for Carnival in blue, teal and purple beads and feathers, surrounded by faces of every color — descendants of enslaved people from Africa, indentured servants from India, and the Amerindians who were here when Europeans arrived. I strolled through black neighborhoods with my two children in tow, with no concerns about whether we stood out as outsiders. I sat on my patio with my mother and sipped coffee, finally at peace.

The struggle continues to make America be like its founding myth and dream.

Because few black people in America have such choices, the struggle continues to make America be like its founding myth and dream. Langston Hughes expressed this dilemma well in the first few stanzas of his poem “Let America be America again”:

Let America be America again.

Let it be the dream it used to be.

Let it be the pioneer on the plain

Seeking a home where he himself is free.(America never was America to me.)

Let America be the dream the dreamers dreamed—

Let it be that great strong land of love

Where never kings connive nor tyrants scheme

That any man be crushed by one above.(It never was America to me.)

O, let my land be a land where Liberty

Is crowned with no false patriotic wreath,

But opportunity is real, and life is free,

Equality is in the air we breathe.(There’s never been equality for me,

Nor freedom in this “homeland of the free.”)

Until whites realize the truth in Hughes’s poem, there will be little hope for an America as free as the myth and the dream of what could be.

We are hearing calls now to be anti-racist; that is, to confront racism wherever it is found. A white friend of mine died recently at nearly 90 years of age. She and her husband first moved to Austin 50 years ago and were house hunting. While looking at one house, she overheard the realtor tell a black couple that the house had been sold. As the black couple left, she asked the realtor about looking at other houses since the house they were looking at was sold. The realtor explained that he told them that because he was unwilling to sell to blacks. Upon hearing that, my friend told the realtor that, in that case, they would find another realtor and she and her husband left. That is a modest example of being anti-racist long before the current era.

It is just such actions (and more) that are needed. It is not enough for those of us who are white to believe that we are not racist, which is unlikely. We need to actively oppose racism in all of its forms, especially if we enjoy the benefits that attach to being white. We know we benefit from being white (whether we ask for it or not) if the mere fact of being white creates no unusual pressures on us or concern us as we go through our daily lives. It is certainly true that having dark skin is a constant pressure and concern in America for those identified as black, whether we acknowledge it or not.

To oppose racism, we don’t have to agree with all of the demands and slogans of those now engaged in protests against police brutality toward blacks. But we should recognize that policing started in this country to protect businesses, and in the south the business was slavery. If we want a more just, equitable, and free society, police organizations must be redesigned and reconstructed to serve, protect, respect, and help everyone, especially those for whom being black has always been a crime, sometimes literally — sometimes metaphorically.

[Rag Blog columnist Lamar W. Hankins, a former San Marcos, Texas, City Attorney, is retired and volunteers with the Final Exit Network as a coordinator for people in seven states and serves as editor, contributor, and moderator of The Good Death Society Blog, which discusses a wide range of end-of-life issues.]

- Read more articles by Lamar W. Hankins on The Rag Blog.

Voice of experience. Thank you, Lamar.

I know the late friend of yours who walked out on the racist realtor. She actually worked on open housing campaigns as well in two cities and was a tremendous person and a good influence on all who came in contact with her. I miss her terribly. Thank you for remembering her.

Good stuff. Thanks for posting.