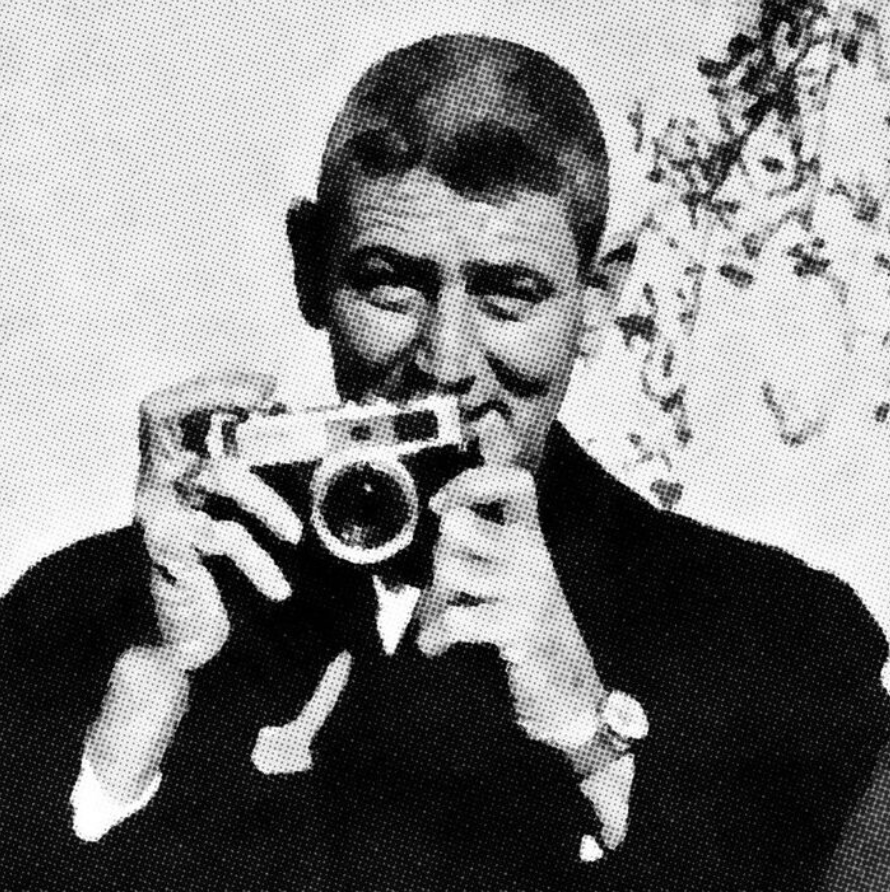

Photo by Belmer Wright published in Austin’s underground paper, The Rag, January 15, 1968.

By Martin Murray / The Rag Blog / August 19, 2025

Lt. Burt Gerding served in the Austin Police Department (APD) in the Criminal Intelligence Division from the early 1960s to some time in 1970, when he was transferred to the APD Narcotics Division. As an APD Intelligence Officer, Gerding worked in concert with the University of Texas Police Department (UTPD) and the FBI. He was primarily responsible for monitoring the activities of suspected campus radicals and leftist student political organizations. Through his friend George Carlson (an FBI agent and Head of Security for University of Texas System), Gerding worked with agents from the FBI’s secret Counterintelligence Program, known as COINTELPRO.

First Encounters of a Special Kind

My first personal encounter with Burt Gerding came in late November 1967, just a few weeks after I starting going to SDS meetings on the University of Texas campus. As I was casually walking along a hallway in the University Union late one morning, I passed two middle-aged men in cheap suits, one of whom I recognized as Burt Gerding. Burt greeted me cheerily with a hearty “Hey, Martin, so you’ve joined SDS.” I realized at that moment my presence had been noticed. That was my introduction to the world of police spying on the anti-war movement.

As I learned later, starting around 1963, and perhaps into late 1968, Burt and his sidekick Allan Hamilton (Head of the UT Austin campus police Department) were regular fixtures around political events on the UT Austin campus. They monitored protest events, spied on political organizations, recorded our names, and identified our “leaders.” We routinely identified them to everyone around whenever they appeared. By the beginning of 1968, I rarely saw Burt Gerding again, except when he hovered around the edges of large demonstrations.

I first learned who Burt Gerding was a few weeks earlier. In mid-November 1967, I accidentally came upon a “sit-in” protest against Marine recruiters in a large alcove room about 30 feet long and 25 feet wide in the University Union. Around eight to 10 people were sitting on the floor, blocking access to the Marines. They were chanting “end the war in Vietnam,” and such. I was captivated. I immediately joined the sit-in. For the next several days during that week, I joined the protest as a participant. During this week of the Marine Recruiters sit-in, counterprotesters jeered at us, pushed their way through the bodies on the floor, stomping and kicking. I noticed several middle-aged men watching the protest from the far edge of the crowd. Some of the protesters blocking access to the Marines told me that the tall thin one with a sly grin on his face was Lt. Burt Gerding, the well-known head of the Austin Police Department Criminal Intelligence Division (euphemistically called the “Red Squad”).

I learned that Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) had sponsored the sit-in protest. I started attending SDS meetings. At last, I had found like-minded people who shared by political views.

Burt Gerding was a visible and ubiquitous presence at political meetings and protest gatherings. He was always lurking around, looking puffed up and self-important. By early 1968, as I recall, whenever we saw him, we pointed him out and heckled him. Soon thereafter, he moved further into the background, giving up on the idea of sitting in on meetings and trying to listen to conversations.

As the antiwar movement expanded from a small group of readily identifiable individuals into a mass movement, the Austin “Red Squad” (with Gerding at the helm) switched strategies and tactics. They began to infiltrate the growing anti-war and anti-racist movement with undercover informants. In retrospect, I now see that police informants consisted of two types. One type was those who attended meetings and hovered at the edges of protests, taking notes and sometimes photographs. These undercover agents pretended they were casual observers. The second type were those who actively participated in organizing efforts, blending into the “movement” as activists, pretending to be our comrades.

When SDS meetings grew in size, sometimes numbering well over 100 or 200 activists prior to planning a major demonstration, it was impossible to detect undercover informants patiently taking notes and preparing reports for whatever policing agency they worked for (the Austin Police Department, the FBI, or the University of Texas Public Security Unit). The role of undercover police agents who actively participated was also difficult to detect. But their purpose was clear: gain access to inside information by “being one of us.” Sometimes this participation spilled over into the role of agents provocateurs, spreading rumors, exaggerating differences, and provoking dissent.

The Gerding Papers at the Briscoe Center for American History (UT Austin)

After he left the APD and then retired from his security job at Westinghouse, Gerding donated a treasure trove of printed materials he had collected over the years to the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, located (of all places) at the LBJ Library on the UT campus. These materials (and especially a transcribed series of interviews he provided to the Briscoe Center in 1994) provide a window into his modus operandi, his worldview, and his plan of attack to disrupt the antiwar movement.

The Burt Gerding Papers constitute an archive as such: they consist of materials produced at the time and gathered together and stored in six boxes, each of which is divided into individual files. These collected materials resemble something akin to a random assortment of printed materials, the most interesting of which focus on “political activism,” political protests, civil rights and black power, and organizations like Students for a Democratic Society, Student Mobilization Committee, and others. Many of these files contain an assortment of old leaflets, occasional undercover police reports, copies of the underground newspaper, The Rag, and some newspaper clippings.

The files are at best loosely classified, devoid of any semblance of temporal sequence, and incomplete as documentary evidence. What should be clear from the start: the Gerding Papers do not even gesture toward a history of political activism in Austin, the ideologies that drove it, or its wider meanings. There are no reports on particular demonstrations or protest events, with the exception of the Don Weedon Gas Station Protests (3 May 1968), Waller Creek tree removals (21-23 October 1969), and the Chuck Wagon riot (10 November 1969). But even these reports are not historical accounts. They are surprisingly thin on recounting how SDS and other organizations planned marches, what routes protesters selected, and what banners were flown. The materials in the Gerding Papers are devoid of analysis.

The Gerding Papers do include reports from undercover informants. The principle mode of information exchange is contained in what were called “Memos of Information.” Undercover informants submitted short (two-page) summaries of what happened at a particular meeting on a particular date. The ritual included who called the meeting, where it was held, the date it occurred, how many were in attendance, who chaired, what were the main points of contention, what factions were present, and what decisions were reached. Some of these reports talked about divorces, and who was responsible for breaking up marriages.

For example, in one “Memo of Information” the informant claimed that Paul Turner and I were calling for a demonstration to disrupt the annual NAVY ROTC parade. This event never appears in any other files. Another example, there are several “Memos of Information” that turn their attention in late 1968 and early 1969 to the New Left Education Project (NLEP), an SDS-sponsored group, and its literature table. Praise is heaped upon the University administration for waiting for the right moment to act. No mention is ever made that Alan Locklear and I were brought before a University Disciplinary hearing, charged with “selling literature” without authorization on campus. We obtained the services of an ACLU attorney, Gerald Lefcourt, and we argued that we were not “selling literature,” but only accepting donations. Besides that, we also argued that fraternities and sororities openly sold tickets for such revolting events as “Round Up” (where sorority women were lassoed and dragged off to makeshift corrals), and the Old South Day dance and party (where frat boys on horses paid young African-American kids to hand-carry invitations to sorority houses).

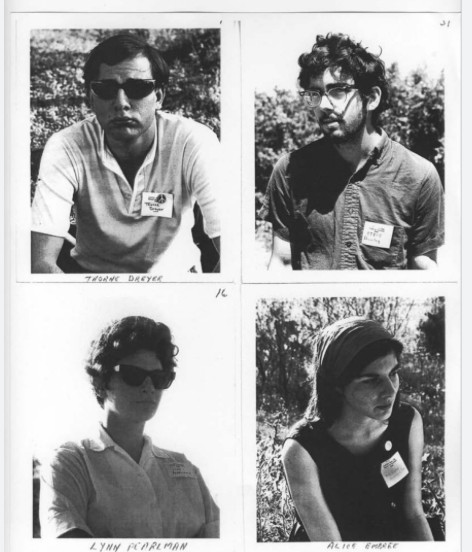

Most likely police surveillance photos. Top on the left is Rag Blog editor Thorne Dreyer, and at the lower right is Rag Blog associate editor Alice Embree.

In 1970, Gerding prepared a Report for Chief Miles, a five-page document included in his Papers. In this document, Gerding offers his assessment of Movement organizations. Indeed, for someone who claims to have reliable undercover informants, and to have infiltrated organizations and secretly reported on meetings, this assessment was pathetic. It was incomplete, relied on deductive tropes about Communist organizations, and was incomplete in its coverage. As our Movement grew in strength and numbers, he seems to have fallen back on well-worn truisms that no longer (if they ever were) instructive. His claims to have his finger on the pulse of the Movement were only matched by his woefully inadequate ignorance of what the Movement – its people and organizations – were actually doing. We were building organizations to confront the war machine, racism, misogyny, and homophobia. Gerding was trapped in old paradigms and analytic frameworks inherited from the 1950s Cold War. He was obsessed with tracing poplar protests back to one of several national “Communist” organizations – CPUSA, Socialist Workers Party, and Progressive Labor. While these organizations had a presence in the Austin Movement, their members were certainly not orchestrating or leading popular protests. By 1970, both the CPUSA and PL were spent forces in Austin, and we regarded the SWP and its offshoot sibling organizations — the “Trots” as we called them — as more or less irrelevant. Gerding seems to epitomize the banality of evil: a self-deluded ordinary “little man” who believed that he could act with impunity because he operated under the official sanction of the security agencies he worked with.

In the Gerding Report, what he ignored was much more important than what he included as part of the official record. CPUSA membership never amounted to more than three or four persons, led by Marian Vizard before she took a decided detour into countercultural and feminist politics. After the break-up of SDS in summer 1968, PL was a spent force in Austin, attracting ever-dwindling numbers to its events. The Spartacists league, never more than perhaps five hardcore fanatics, always carried their banner to every rally and demonstration: “all Southeast Asia must go Communist.” As quasi-Maoists, their political position was that the Vietnamese revolution — both in the North and South — was hopelessly revisionist because of the support the Vietnamese obtained from the Soviet Union. This arcane political position was never going to be a way to build a vibrant political movement in Austin. The “Sparts” were pathetically irrelevant — a nuisance that we tolerated.

After correctly assessing the declining significance of the CPUSA and PL, Gerding anointed the SWP and YSA with an oversized and exaggerated role. He erroneously, and ridiculously, attributed the bulk of organizing anti-war rallies and marches to the SWP/YSA/SMC trioka. This claim is so out of touch with reality that it is ridiculous. I believe that Gerding was unable to think outside of the box of organized Marxist-Leninist parties. He tried to squeeze all political expression into this model of outside meddling and interference.

Towards the end of his Report, Gerding focuses on the Motherfuckers, a small sect of drug-dealing hippies, who contributed virtually nothing to the political movement. They were flamboyant for sure, but were living on the edge both of reality and of Austin. The Motherfuckers showed up for demonstrations, and were always loud and intimidating. But they eschewed politics other than espousing a kind of libertarian-anarchist stew of anti-establishment ideas.

In his treatment of the anarchist movement, Gerding focuses on the Gerard Winstanley Memorial Caucus, a small cadre of Sociology graduate students and their friends. I was involved in this effort, but it paled in comparison with broader anti-war activities and organizations with which I was aligned. The Gerding Report fails to even mention any of the broader antiwar movement, which by this time was larger than ever.

One has to ask: why was this Report so incomplete, so filled with silences and omissions, and so erroneous in its attribution of the driving force for anti-war rallies and demonstrations? Logically speaking, there are only two possible explanations. First, Gerding was deliberately telling Chief Miles, the head of APD, what he thought his boss (and FBI National headquarters) wanted to hear. Second, Gerding actually did not know what was happening, either through sloppy detective work, or through an inability to connect the dots of militant radicalism right before his eyes. Perhaps Gerding was losing interest in his job. Seen retrospectively, this Report appears towards the end of his career as head of criminal intelligence division.

If this report is the best that the Head of the Criminal Intelligence Division can produce, we activists had little to fear from their incompetent sleuthing. This Report did not help their cause of gathering information, sifting through it, and arriving at a clear-headed analysis. But at the end of the day, the problem is that these policing agents had the power of the security apparatus to back them up.

To be sure, documents never reveal everything. What I have obtained from reviewing these police files constitutes only a thin layer of deeper levels of intrigue. It is truly impossible to know what they knew — or thought they knew.

After reading the Gerding Papers, one of the security practices that stands out is the fixation on “naming names.” Handlers instructed undercover police agents to record the names of those who attended meetings. To give one example, a police informant reported on a GI-Civilian Picnic attended by approximately 75 persons (including “30-40 who appeared to be GIs”) held in a park in Austin on July 19, 1970. For obvious reasons, active-duty GIs were extremely reluctant to reveal their true identities. Despite these precautions, the police informant was able to identify three GIs by name and to list virtually all non-GIs who attended the picnic. Perhaps unknowingly or even inadvertently, they passed along information that passed for truth. On occasion, the depth of interest was surprisingly detailed. Some notes refer to meetings attended by as few as ten people.

The Gerding Interviews: Lt. Burt Gerding and His Fantasy World of Espionag

[Burt Gerding] is a frightening person, mostly because he is so blind to the realities of others and so narrow in his vision of the world. Combine these qualities with his passion for the use of force, including deadly force, to impose what he sees as correct behavior, and you’ve got a person as terrifying as any Gestapo member. He is exactly the kind of person joining militias across the country and advocating the killing of federal officials and the bombing of government institutions.

Email notes from the archivist Sarah Clark, 5 April 1996, stored in Holding Record for the Gerding Papers Collection [Dolph Briscoe Center, Burt Gerding Papers Holding Rec

Available at <https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/c6d790bef28148b79b11902a8acea71e

The Gerding Papers contain a startling document: a three-part interview (only partially completed) with Lt. Burt Gerding conducted by Sarah Clark on 19 September 1994, continued on 10 October 1994, and resumed on March 25, 1995. This third interview is found in a separate box and under a different file name. This interview material does not receive any particular pride of place, but instead is buried toward the end of his Collected Papers, appropriately labeled “Gerding oral history interview [cassette tapes and transcript].”[1]

The two-part interview transcript for 19 September 1994 and 10 October 1994 itself is quite lengthy: 53 single-spaced pages. The interview takes the form of a confessional treatise. It resembles a personal diary organized as if by a collection of random thoughts, a stream of consciousness spoken aloud and transcribed by another person. Sarah Clark poses a range of questions to Gerding, allowing him to ramble on (sometimes almost incoherently) most of the time. He is surprisingly candid, seeing no need to cloak his real and imagined exploits in a veneer of official and professional legitimacy. He is clearly bragging.

From this interview and from a number of written reports included in the Gerding Papers, it is possible to piece together a composite image of the man and his work as a law enforcement officer involved in criminal intelligence. For me, three themes stand out: first, he was a dedicated police officer who recognized no fixed boundaries of legal propriety that restricted what he might do, or imagine he could do. He openly admits with prideful arrogance about engaging in illegal acts. Second, he possessed a rather shoddy, incomplete, and naive understanding of the antiwar Movement he devoted his adult life to disrupt and dismantle. He seemed to possess no interest in grasping what motivated political activists to act in ways that put them sometimes at grave risk. Third, he seems to confuse and blend fantasy and reality, making improbable claims that are impossible to verify, but also impossible to believe. He comes across as a kind of pathetic figure who substituted “dirty tricks” for careful surveillance and intelligence-gathering work. Gerding was at once a merry prankster (using his power to have “fun” with frightening activists), a pied piper (who bragged about his recruitment of undercover informants), and a rogue cop (willing to break the law).

Burt Gerding brought the unseemly qualities of huckster, trickster, and charlatan to his job. He was an unprincipled man, who delighted in abusing the official powers bestowed upon him as a police officer bound to enforce and uphold the rule of law. At every opportunity, he cloaks himself in virtue, putting himself on the side of angels, justifying his unwarranted behavior as an expression of his imaginary struggle of good versus evil. Like the Leonard Zelig character in the 1983 Woody Allen film Zelig, Gerding locates himself at the center of the “action,” claiming — in his own words — “I knew everything that was going on, Everywhere” (Interview 3, p. 83). Similarly, like the trickster Tom Ripley, in the 1999 psychological thriller film, The Talented Mr. Ripley, Gerding sometimes seemed more intent on pretending to be a competent criminal intelligence officer than actually functioning as one.

While the description of the “Many Faces of Burt Gerding” may offer a glimpse into the multiple sides of his personality, it is also necessary to acknowledge that he often strayed from factual accuracy. In his three-part interview, not only did Gerding stumble over names of people and mis-remember dates of events, he also concocted such “wild tales” of his personal exploits so preposterous that they strain any semblance of credulity.

In carrying out his official duties as head of the Criminal Intelligence Division, Lt. Burt Gerding was at once a “jolly prankster,” a law-breaking vigilante, and a pathetic figure who suffers from delusions of grandeur. He seemed obsessed with his work, gleeful about making political militants and radical activists feel uncomfortable when he encountered them. He was bombastic, self-aggrandizing, and downright arrogant. At times and places, he allowed wishful-thinking to replace actual facts, and seems totally uninterested in what motivated people to action. Much of his bravado consisted of the fantasy meanderings of a law enforcement officer who saw himself as outside conventional legal restraints.

In describing his preferred modus operandi, Burt Gerding proclaimed: “I spent my afternoons and days a lot of times going over to the Chuck Wagon, and buying coffee and sitting down at a table.” As he put it, “and the next thing you know, I’d have a tableful of people, and all of these people are interested in what I’d be doing because they knew I was doing something and they were trying — they were trying to find out from me” (Interview 2, pp. 30, 42). Gerding seemed to revel in what he considered to be his uncanny capacity to charm young people. Like the Venus Flytrap, he believed he could capture them with his cleverness and his charm.

At this time, there was a national TV program called the “Mod Squad.” The leader of this undercover police team was named Captain Greer, and he had a couple of white and black kids working for him. As Gerding explained his recruitment strategy: “I’d sit there [drinking coffee in the Chuck Wagon], and look ‘em in the eye, and I’d say ‘how would you like to be in my Mod Squad?’ One of ‘em, Sally, said, ‘could I, really?’ And I said, ‘you might could. Think about it. So she calls me up later and says, ‘I’ll come in only if you let my friend in.’ And so I said, ‘who is your friend?’ So she tells me and so I say, ‘so you and your friend meet me tonight at the parking lot of such-and-such a place and we’ll see about it’. Now that’s where I recruited Sally and Sam. And they were two of the best I had. Sam was highly intelligent. He’s now a physician” (Interview 2, p. 45). Gerding expressed a great deal of pride when he said: “They’d call me Capt’n Greer because they identified with being in the Mod Squad.” He concluded: “This was just another one of my methods for recruitment and control” (Interview 2, p. 45).

In order to make his undercover informants feel important, he put ski masks on them and let them ride around with him at night. He drove his undercover informants to the police station “with a paper sack over their head,” and “let them look through some of my files and see how I operated and everything. So — they were really tickled because they kind of felt like they were part of the Police Department” (Interview 3, p. 73). He also took “his little agents” (as he put it) out to a dump near Lake Travis and let them fire a semi-automatic rifle he had confiscated. This special treatment was meant to keep his undercover agents in line.

Gerding gloated that he used counterintelligence — “dirty tricks” — before he learned of the elaborate plans undergirding COINTELPRO. For him, counterintelligence meant using the information he gathered against what he termed “the enemy.” “If you find that there’s something vulnerable that the enemy has, then you strike it, and your counterintelligence people do that. So I had been using counterintelligence all along, in various and sundry ways” (Interview 2, p. 32).

Whether outside the boundaries of the law or not, he endorsed and engaged in a pro-active campaign of disruption. Gerding boasted about using his repertoire of “dirty tricks” to frighten activists, disrupt meetings, and generally foster uncertainty. He bragged endlessly about spreading unfounded rumors, engaging in unwarranted breaking-and-entering homes of known activists, flattening tires, tapping phones, photographing unsuspecting people, and disrupting meetings with fireworks.

Let us look at some of these “dirty tricks” in more detail. Gerding boasted that he knew that an FBI undercover informant with whom he developed a working relationship – a person who came to the FBI from military intelligence — broke into people’s homes and taped marijuana cigarettes in discrete places. He did nothing to stop these kinds of “dirty tricks” to possibly entrap antiwar activists in criminal behavior (Interview 2, pp. 30-31). At the time, possession of marijuana was punishable with up to 10 years in prison. Gerding’s inaction made him complicit in a crime. It is clear that Gerding stepped over the line of legality when it suited his purposes. In this instance, there was an air of deniability.

Gerding boasted about his homemade electronic bugs used to wire-tap the phones of known activists. He justified his illegal wire-tapping by claiming those he targeted were “members of one Communist Party or another.” He said he was interested in finding out “if they were getting any orders from somewhere else or what they were saying to other places.” Gerding claimed that he worked with an “electronics expert” who helped him construct a tiny telephone bug that fit into a small box that was sealed with epoxy adhesive to make the device almost indestructible. He said that he wore “climbing shoes with spikes” so that he could easily ascend telephone poles. He said he would venture out at “two, three, or four o’clock in the morning, “by myself, I wanted to make sure nobody knew about it.” He claimed that he installed these telephone bugs before they were illegal (Interview 3, 113-115).

Gerding insisted that almost every night he drove around with his undercover informants outfitted with black ski masks, “check[ing] out at least 20 or 30 of these people’s residences to keep tabs [on them] and where they were or what they were doing.” He claimed that “a lot of times” on nights when regularly scheduled meetings were held, “I would park my car several blocks away, sneak up to the front porch and detonate a [large] M-80 firecracker.”

Gerding was totally cavalier about engaging in harassment practices that had nothing to do with police surveillance work. He claimed that he was able to get the Student body president and “hippie” named Jeff Jones to believe that his house was “bugged” with listening devices. As Gerding put it, “I saw an opportunity to just kinda have some fun” (Interview 3, p. 92). This offhanded comment provides a window into understanding Gerding’s motivations and intentions. What does “having fun” have to do with serious criminal intelligence work? Nothing. He abused his official authority to play a “side game” designed to “freak out” Jeff Jones. In communication with me, Jeff Jones disputed these “facts,” claiming nothing of this sort ever happened. It seems that Gerding engaged in make-believe. He was the consummate fabulist. Whether he believed his own falsehoods is a matter of speculation. The alleged harassment of Jeff Jones – whether it took place or not – strongly suggests that Gerding saw himself as a prankster with a badge. He seemed to believe that he had license to do whatever hewanted.

Burt Gerding was not adverse to fantasizing about the discretionary use of arbitrary police violence. In responding to what he interpreted as the threat from Communist Party member Bob Speck in 1967 to “kill him,” Gerding boasted that at “any time I wanted I could just wipe him out” (Interview 1, p. 28). Why would a police officer say what he said, let alone imagine it? In fantasizing about his own omnipotent power to do deliberate harm to political dissenters, Gerding expressed his utter contempt for the rule of law

Undercover Informants

Those who collected and stored these documents sometimes inadvertently made mistakes and revealed the identities of political informants. One batch of the Gerding Papers contained photocopies of parcels addressed to Barbara Roseman — a person who turned out to be an undercover agent. It seems in all likelihood that Barbara received pamphlets from New York and elsewhere, and that office staff at APD mistakenly included these in the Gerding file cabinet.

A note that identifies its author as Jack Steell, dated June 9, 1970, reports on the whereabouts of Jeff Jones, a known Austin activist who was later elected student body president at UT. It was not until years later that by pure accident a former SDS activist discovered Barbara Roseman working as a personal secretary for Burt Gerding after he left the APD. Barbara passed away several years back. In my sleuthing, I contacted a member of her family by phone. This person confirmed that Barb worked for Burt Gerding.

There were a number of undercover police informants who attended political meetings and spied on us. Early on, we identified one such undercover informant, an older non-student we routinely called “Nick the Cop” to his face. He always volunteered to gather names and addresses of those in attendance. He approached newcomers, acting like an important SDS activist. He had no visible source of income, and claimed he lived off an inheritance. He disappeared for months.

Certainly for me, the one who got away was Barbara Roseman. She came to Austin from Dallas with her friend whom I will refer to as Melvyn. Barbara quickly fit into the “movement.” While I never detected even the slightest hint of political ideology or commitment on her part, she often represented the Austin SDS chapter at regional meetings. She often chaired raucous meetings where the various factions of SDS shouted and yelled. Interestingly enough, Barbara’s name often appeared in “Memos of Understanding.” One can only wonder if the undercover informant preparing the “Memo of Information” understood that Barbara was also working undercover.

In fall 1972, suspicion fell on Melvyn. We had planned a demonstration at an army recruitment site close to downtown scheduled to begin in early afternoon. That morning, a fellow-activist just happened to be traveling near the site of the proposed demonstration, but several hours before the scheduled start. He observed Melvyn getting out of a police car. When we confronted Melvyn, he claimed that it was cold and he as only asking for a light for a cigarette. Nevertheless, we began to suspect him of undercover work.

The End of the End

Poor Burt. He spun the wheel of fortune and lost. In the early 1970s, Burt Gerding became enmeshed in an internal imbroglio in the APD involving the issuance of traffic tickets to a fellow officer. Apparently, Gerding was too quick to go to the press report on this internal matter. Perhaps it violated the unspoken rule that “what happens with the police, stays with the police.” As a consequence of this apparent indiscretion, Chief Miles relieved Lt. Gerding of his duties as head of Criminal Intelligence Division and transferred him to the narcotics division. Perhaps this transfer to another department was seen as a demotion since Gerding began his police career in narcotics. I am sure that Burt saw this transfer as a personal blow. So all in all, Gerding’s ignominious career as anti-communist crusader lasted less than six years. It was a meteoric rise and a fast collapse. Within a year or so, Gerding retired from the APD and took a job as head of security at Westinghouse Corporation outside of Austin. Then as now, I think of Burt Gerding as a kind of pathetic character, a man really worried that the countercultural movement was destroying his sense of propriety, his sense of right and wrong, and about how respectful young people ought to behave toward their elders.

[1] Three interviews conducted by Sarah Clark (19 September 1994; 10 October 1994; and 27 March 1995) for the Briscoe Center. Available in the Burt Gerding Papers. Box 4Zf353_Gerding Oral History Interview Transcript [partial], 1994_; and Burt Gerding Papers. Box 2X209b_Transcripts_. Interview with Sarah Clark. References to this three-part interview are referred to in the text, respectively, as Interview 1, Interview 2, and Interview 3, followed by page numbers.

[Martin Murray is the author of Insurgent Politics in the Lone Star State: Remembering the Anti-War Movement in Austin, Texas, 1967-1963, published by the University of North Texas Press.]

Information contained herein regarding Barbara Roseman is false, She hired on at Westinghouse in 1973 as a production coordinator in the components assembly department, where I worked, she was friends with Burts nephew, they got caught with some pot and the nephew had Burt pull strings to get them off. I had a long friendship with Barb, she got me in at Dixies Bar and Busstop as a bartender, introduced me to Terry Allen, Guy Clark, the Flatlanders and many others (Marcia Ball!). She was as far left as one could get. she NEVER worked as Burts secretary. I knew Jerk Gerding all too well, he was a clown