No more bubblegum:

Occupy Wall Street’s magic glasses

As [John] Carpenter foresaw, force enough Americans out of their homes and/or careers… and something new and huge will begin to slouch toward Goldman Sachs.

By Mike Davis / Los Angeles Review of Books / October 20, 2011

Who could have envisioned Occupy Wall Street and its sudden wildflower like profusion in cities large and small?

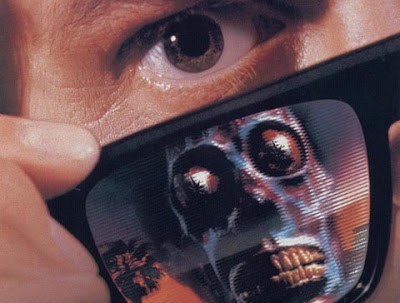

John Carpenter did. Almost a quarter of a century ago (1988), the master of date-night terror (Halloween, The Thing, etc.) wrote and directed They Live — depicting the Age of Reagan as a catastrophic alien invasion. It remains his subversive tour de force.

Indeed, who can ever forget the brilliant early scenes of the huge third-world shantytown reflected across the Hollywood Freeway by the sinister mirror-glass of Bunker Hill’s corporate skyscrapers?

Or Carpenter’s portrayal of billionaire bankers and evil mediacrats ruling over a pulverized American working class living in tents on a rubble-strewn hillside and begging for casual jobs?

From this negative equality of homelessness and despair, and thanks to the magic dark glasses found by the enigmatic “Nada” (played by Roddy Piper), the proletariat finally achieves interracial unity, sees through the subliminal deceptions of capitalism, and gets angry. Very angry.

Yes, I know, I’m reading ahead. The Occupy the World movement is still looking for its magic glasses (program, demands, strategy, and so on) and its anger remains on Gandhian low-heat.

But, as Carpenter foresaw, force enough Americans out of their homes and/or careers (or at least torment tens of millions with the possibility) and something new and huge will begin to slouch toward Goldman Sachs. And unlike the “Tea Party,” so far it has no puppet strings.

One of the most important facts about the current uprising is simply that it has occupied the street and created an existential identification with the homeless.

Quite frankly, my generation, trained in the civil rights movement, would have thought first of sitting in the buildings and waiting for the police to drag and club us out the door. (Today, pepper spray and “pain compliance techniques” are preferred by the cops.)

In 1965, when I was just 18 and on the national staff of Students for a Democratic Society, I planned a sit-in at the Chase Manhattan Bank, “a partner in Apartheid” for its key role in financing South Africa after the massacre of peaceful demonstrators. It was the first protest on Wall Street in a generation

I still think that taking over the skyscrapers is a splendid idea, but for a later stage in the struggle. The genius of Occupy Wall Street, for now, is that it has temporarily liberated some of the most expensive real estate in the world and turned a privatized square into a magnetic public space and catalyst for protest.

Our sit-in 46 years ago was a guerrilla raid; this is Wall Street under siege by the Lilliputians. It’s also the triumph of the supposedly archaic principle of face-to-face, dialogic organizing. Social media is important, sure, but not omnipotent. Activist self-organization — the crystallization of political will from free discussion — still thrives best in an actual urban fora.

Put another way, most of our internet conversations are preaching to the choir; even the mega-sites like MoveOn.com are tuned to the channel of the already converted, or at least their probable demographic.

The occupations likewise are lightning rods, first and above all, for the scorned, alienated ranks of progressive Democrats, but, in addition, they appear to be breaking down generational barriers, providing the missing common ground, for instance, for imperiled middle-age school teachers to compare notes with pauperized young college graduates.

More radically, the encampments have become symbolic sites for healing the divisions within the New Deal coalition inflicted during the Nixon years. As Jon Wiener observes in his always smart blog at www.TheNation.com, “hard hats and hippies — together at last.”

Indeed. Who could not be moved when AFL-CIO president Richard Trumka — who had brought his coalminers to Wall Street in 1989 during their bitter, but ultimately successful strike against Pittston Coal Company — called upon his broad-shouldered women and men to “stand guard” over Zucotta Park in the face of an expected attack by the NYPD?

Although old radicals like me are too apt to declare each new baby the messiah, this child has the rainbow sign. I believe that we’re seeing the rebirth of the quality that so markedly defined the ordinary people of my parents’ generation (migrants and strikers of the Great Depression): a broad, spontaneous compassion and solidarity based on a dangerously egalitarian ethic:

Stop and give a hitch-hiking family a ride. Never cross a picket line, even when your family can’t pay the rent. Share your last cigarette with a stranger. Steal milk when your kids have none and then give half to the little kids next door (this is what my own mother did repeatedly in 1936). Listen carefully to the quiet profound people who have lost everything but their dignity. Cultivate the generosity of the “we.’”

What I mean to say, I suppose, is that I’m most impressed by those folks who’ve rallied to defend the occupations despite often significant differences in age, social class, and race. But equally, I adore the gutsy kids who are ready to face the coming winter on freezing streets, just like their homeless sisters and brothers.

But — back to strategy — what’s the next link in the chain (in Lenin’s sense) that needs to be grasped? How imperative is it for the wildflowers to hold a convention, adopt programmatic demands, and thereby put themselves up for bid on the auction block of the 2012 elections? Obama and the Democrats will certainly and perhaps desperately need their energy and authenticity.

But the occupationistas are unlikely to put themselves or their extraordinary self-organizing process up for sale. Personally I lean toward the anarchist position and its obvious imperatives.

First, expose the pain of the 99 per cent, put Wall Street on trial. Bring Harrisburg, Laredo, Riverside, Camden, Flint, Gallup, and Holly Springs to downtown New York. Confront the predators with their victims. A national tribunal on economic mass murder.

Second, continue to democratize and productively occupy public space (i.e. reclaim the Commons). The veteran Bronx activist-historian Mark Naison has proposed a bold plan for converting the derelict and abandoned spaces of New York into survival resources (gardens, campsites, playgrounds) for the unsheltered and unemployed. The Occupy protestors across the country now know what it’s like to be homeless and banned from sleeping in parks or under a tent. All the more reason to break the locks and scale the fences that separate unused space from urgent human needs.

Third, keep our eyes on the real prize. The great issue is not raising taxes on the rich or achieving a better regulation of banks. It’s economic democracy — the right of ordinary people to make macro-decisions about social investment, interest rates, capital flows, job creation, global warming, and the like. If the debate isn’t about economic power, it’s irrelevant.

Fourth, the movement must survive the winter in order to fight the power in the next spring. It’s cold on the street in January. Bloomberg and every other mayor and local ruler is counting on a hard winter to deplete the protests. Thus it’s all important to reinforce the occupations over the long Christmas break. Put on your overcoat.

Finally, we must calm down — the itinerary of the current protest is totally unpredictable. But if one erects a lightning rod, we shouldn’t be surprised if lightning eventually strikes.

Bankers, recently interviewed in The New York Times, seem to find the Occupy protests little more than a nuisance based, they claim, on an unsophisticated understanding of the financial sector.

They should be more humble. Indeed, they should probably tremble before the image of the tumbril

Four-and-one-half million manufacturing jobs have been lost in the United Sates since 2000 and an entire generation of college graduates now face the highest downward mobility in American history. Since 1987, African Americans have lost more than half of their net worth; Latinos, an incredible two-thirds.

Wreck the American dream and the common people will put some serious hurt on you. Or as Nada explains to his unwary assailants in Carpenter’s great film:

“I have come here to chew bubblegum and kick ass… and I’m all out of bubblegum.”

[Mike Davis is a Distinguished Professor in the Department of Creative Writing at the University of California, Riverside. An urban theorist, historian, and social activist, Davis is the author of City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles and In Praise of Barbarians: Essays against Empire. This article was written for the Los Angeles Review of Books and was cross-posted to The Rag Blog. Read more articles by Mike Davis on The Rag Blog.]

with scholar, activist, and urban theorist Mike Davis:

- Read more Rag Blog coverage of Occupy Wall Street and Occupy Austin.

I think that was a wrestler named “Rowdy” Roddy Piper or something that was all out of bubblegum… great idea for a movie though. I liked this article

Yup, Roddy Piper played John Nada., not Russell. Good piece though, Mike.

The article has been corrected to credit Roddy Piper — not Kurt Russell — as playing Nada. –.t