image from New Traffic Builder

Coming soon:

Peak oil, peak driving, peak cars

Part IV: The Texas road lobby meets peak oil.

By Roger Baker / The Rag Blog / July 28, 2011

[This is the fourth and final part of a series by Roger Baker on transportation, centering on the issue of peak oil and its ramifications.]

The ‘Pentagon of Texas’

Molly Ivins once called TxDOT (Texas Department of Transportation) “the Pentagon of Texas.” The political clout of TxDOT and the Texas road lobby operating on the state level is still unrivaled.

Inside Texas, TxDOT has held a politically powerful position for many decades, with the help of its traditional political allies like the Texas Good Roads Transportation Association, which was the political base for businesses and civic clubs that might benefit from local application of road money, and the Associated General Contractors, essentially an alliance of private road contracting companies, rather analogous to the defense industry. The contractors gained their institutional power decades ago, when TxDOT stopped building very many roads on its own.

From its earliest days, the Texas Highway Commission, as it was known before it became TxDOT, has been a highly political institution ready to pass out favors to its political allies in the form of road contracts. This snip is taken from an especially scholarly study devoted to the early politics of TxDOT.

It’s more than likely that the conditions of these highways can be seen as a direct legacy of years of county authority and political struggle for control of the department. After all, since its founding in 1917 the Texas Highway Department has, as often as not, been forced to make decisions based on political considerations. Issues such as traffic density and the proportional allocation of funds were often secondary to the job of protecting revenue or just getting roads built.

In Texas, roads gradually became seen as a traditional form of publicly funded entitlement; a kind of welfare to subsidize suburban sprawl development in a heavily urbanized and rapidly growing state.

The way politics works in Texas, there is a traditional alternative to political bribes. Instead, the special interests channel money to Texas politicians through campaign contributions. Quite in line with this approach, the biggest road contractors in Texas contributed over $1 million to Texas Gov. Rick Perry during his first term in office. Later they gave more millions to other Texas politicians.

Since the state solicited its first bids for a leg of the TTC project in 2003, private companies that have landed lucrative TTC contracts have contributed $3.4 million to Texas candidates and political committees — a significant increase in their political activity. TTC contractors also have spent up to $6.1 million on Texas lobbyists since the state solicited their respective bids. While the TTC contains windfalls for some contractors, lobbyists and elected officials, the benefits to Texas motorists and taxpayers are much less clear.

A few years ago, when the late Ric Williamson chaired the Texas Transportation Commission, it became apparent that fuel tax revenues could not possibly keep up with TxDOT’s accustomed pace of road building. Working with Gov. Rick Perry, Williamson ordered TxDOT to try to shift all its new construction to “public-private partnership” toll roads to leverage TxDOT’s limited public funds.

In order to sell private investors on toll road bonds, it is obviously helpful to try to maintain that road demand will keep increasing for decades until the bonds are finally paid off (some toll road bonds, like some issued for US 290 E, pay junk bond rates, but are uninsured against default). The policy is to try to use private toll road bond funding and also federal loans to supplement TxDOT’s traditional but stagnant gas tax revenue, in order to bridge the revenue gap and keep building roads.

As is the case with Indiana Gov. Mitch Daniels, Texas governor Rick Perry is a highway booster. “The highways of Texas are built and paved in part by paths of gold leading to the Texas Governor’s Mansion,” political reporter R.G. Ratcliffe wrote in the Aug. 30, 2002, edition of the Houston Chronicle, in “Highway plans bring money to politicians.”

The political clout of the Texas road lobby still exceeds that of the various competing social needs such as education. TxDOT’s long range road planning policy still stubbornly reflects the same outlook, which involves working hard to perpetuate the notion of ever-expanding growth in future road demand.

However, as the federal data clearly shows, Texas travel is currently falling short of TxDOT’s vehicle travel growth projections, due to a combination of higher fuel prices, a poor economy, an aging population, congestion fatigue, and changing driving behavior, also seen nationally.

The Texas road lobby today

The latest incarnation of the Texas road lobby is arguably Transportation Advocates of Texas (TAoT). A sort of who’s who of current Texas road politics, clearly organized by special interest money. Scroll down to the bottom to see a long list of those interests currently involved in promoting roads — largely banking, construction, engineering, road contracting, and land development interests.

Those familiar with Austin’s federally sanctioned Metropolitan Planning Organization, CAMPO, will see the last two CAMPO directors, Mike Aulick and Joe Cantalupo, listed among members of the road lobby’s supporters.

This snip from an internal document of this same group, TAoT, recently circulated to its supporters, clearly shows that their primary political goal is to get more road money, despite the relatively falling gas tax revenue:

The Great Outstanding Issue: Texas has yet to identify a stable source of additional revenue that can meet the transportation needs of a rapidly expanding population. Fuel efficiency and hybrid vehicles reduce gas tax revenue — and the state fuel tax hasn’t changed in 20 years. Whether it is through taxes, fees, tolls or other sources of revenue, further delays in providing additional financing will inevitably result in more traffic congestion.

By one estimate we under-fund roads by $8 billion a year. The problem will only get worse. Congestion will get worse. Economic losses will get worse. Rural connectivity will get worse. Road conditions and road safety will get worse. And the cost associated with doing nothing means one day the price tag will be worse.

Only roads are mentioned; TxDOT and the road lobby don’t do much transit, except by TxDOT passing federal transit funds down to the local level. Even while admitting that the road funding situation is getting worse with no relief in sight, the focus remains strongly on building roads, as spelled out in this editorial by two top TAoT road lobbyists.

But we are not without solutions. The gas tax hasn’t been increased in 20 years — and its buying power has significantly diminished due to inflation. Vehicle registration fees could be raised and dedicated to high-priority projects. Allowing local officials to access a portion of the gas tax or other sources of revenue would also provide relief. And we can support ending the diversion of highway dollars to spending on other priorities.

The Texas road lobby selects data that

always predicts increasing road travel demand

The Texas road lobby seeks to keep building roads which benefit not only the road contractors, but also the powerful Texas suburban land developers who thrive by planning ever-expanding rings of suburban sprawl around the major metropolitan areas of Texas, a pattern typical of other sunbelt states.

By 2005, about 86% of the Texas population was living in its urbanized areas with only 14% living in the rural areas. Suburban sprawl development has long been made profitable by buying and developing land in the suburban fringe areas. These areas often escape city taxes, but require the help of publicly funded highways to help stimulate development.

This road-assisted urban development formula worked for decades, but it is based on unsustainable trends. Anyone can now see from the federal data that the total travel demand on Texas roads has been flat since about 2007. Here are the yearly VMT numbers for total travel in Texas in millions of miles on state’s roads as measured by the Federal Highway Administration. See for example the 2007 link.

2004 — 231,008

2005 — 235,170

2006 — 238,256

2007 — 243,443

2008 — 235,382

2009 — 230,411

Unfortunately, this useful yearly data series for Texas road travel stopped in 2009. However, using this series we can compare the five most recent Februarys of Texas driving; here again, we can see that the Texas VMT road travel data have continued to stagnate or decrease, on through the most recently reported data:

Feb. 2007 — 17,893

Feb. 2008 — 18,831

Feb. 2009 — 18,953

Feb. 2010 — 18,490

Feb. 2011 — 17,635

Given the nature of road politics in Texas, it comes as no surprise that TxDOT’s long range plan released in May 2010 anticipates a travel demand growth of about 2.44% a year, for decades into the future, as a basis for TxDOT planning. As TxDOT says, “The new Statewide Long-Range Transportation Plan 2035 (SLRTP) will serve as the state’s 24-year “blueprint” for the planning process.

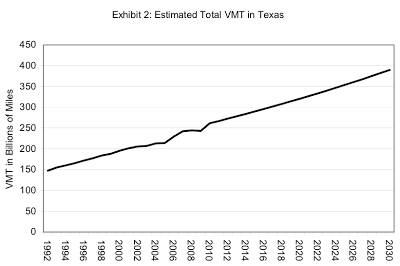

TxDOT’s “Statewide Long-Range Transportation Plan 2035,” released in mid-2010, tries to ignore the current flatness in travel demand as something exceptional and abnormal. It assumes that vehicle miles traveled will somehow recover and then continue to rise steadily as a straight line for decades to come, much as it did before 2005.

The TxDOT long range planners are unable to explain the sharp falloff in traffic volume seen to begin about 2005 — with Texas road travel peaking in 2007 — and now continuing through the most recent data in 2011, or about six years now.

Since the Texas travel data is collected and published by the Federal Highway Administration, the continuing stagnation or decline in vehicle miles traveled on Texas roads is hard for TxDOT to deny. This well-documented reality has caused TxDOT to insert the strange flattened VMT section in the middle of their otherwise ever-ascending long range travel demand chart.

The reality is also that car registrations in Texas peaked in 2005 and then flattened and decreased slightly until 2009, where the most recent FHWA data ends. This data is given in thousands of car (light vehicle) registrations in Texas, 2004-2009, here seen peaking in 2005:

2004 — 8,620

2005 — 8,793

2006 — 8,689

2007 — 8,680

2008 — 8,711

2009 — 8,711

The Texas Road Lobby’s think tank,

the Texas Transportation Institute (TTI)

The Texas road lobby has its own nationally prominent think tank, the Texas Transportation Institute (TTI) based at Texas A&M. TTI functions more or less as an academic wing of the road lobby, implicitly denying peak oil, while focusing primarily on expanding road capacity as the best way to preserve mobility and serve future transportation needs. The TTI outlook on urban traffic congestion and congestion relief — through building more roads for ever more vehicles — is widely disseminated through the media as their main approach to transportation planning policy.

Over the past year, TTI experts answered tough questions on a variety of state and national transportation issues. Over 2,500 newspaper articles, broadcast television spots and professional journals — with a potential reach of over 725 million readers and viewers nationwide — mentioned the Institute or its experts.

For the Texas road lobby to contemplate that the total amount of driving inside the USA may never again exceed the peak reached in 2007, either in Texas or nationally, is considered a heresy.

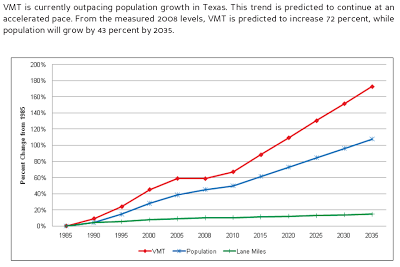

As the charts show, the TTI and TxDOT claim to be able to predict the future numbers of drivers, and the future road demand, thus implying the need to keep expanding road capacity for decades into the future. (Note: car ownership peaked worldwide in 2004.)

The TTI works hard to help us ignore the fact that people are actually driving less, in large part because of higher fuel costs combined with a decreasing family budget. Other factors include an increasing level of rush hour congestion seen in most large U.S. cities as a normal consequence of their growing population.

At the same time, TTI concludes that Texans will always be willing and able to keep driving more, as they have in the past, by means of a transition to more fuel efficient or electric vehicles. This would of course justify the continued building of ever more new roads by the private road contractors.

Since fuel tax revenue has been stagnant compared to the rate of inflation, TxDOT’s gas tax revenue has effectively been decreasing. From the standpoint of road lobby politics, the political path of least resistance is for the road lobby to try to claim that demand for new road capacity will always keep growing as fast as it has in the past.

The road lobby also has an interest in trying to maintain that the increasing fuel efficiency of vehicles is more important than changing driving behavior, thus causing fuel taxes to continue falling short of the funding needed to meet the projected increase in road demand.

In May 2010 Dr David Ellis of TTI appeared before a joint meeting of two top transportation-related committees of the Texas Senate to explain why Texas travel volume will always keep rising, much as it did before 2005. And to argue that future road demand will continue to increase rapidly for decades to come, which implies the need for ever more roads.

Note the similarity between Dr. Ellis’s chart and TxDOT’s VMT charts released about the same time, except in the case of Dr. Ellis’s chart, driving demand is projected to increase even more steadily over time.

Dr. Ellis’s argument is that while Texas may have seen slight decreases in driving before, that these are exceptional and momentary blips, after which the old historic, and presumably normal, increases in vehicles on the road will resume, blind to the rising price of fuel.

The steady increase in driving seen during the decades of cheap oil before 2005 should thus be accepted as the normal situation, and as a proper guide to future spending on roads in Texas (see Exhibit 2 of his report).

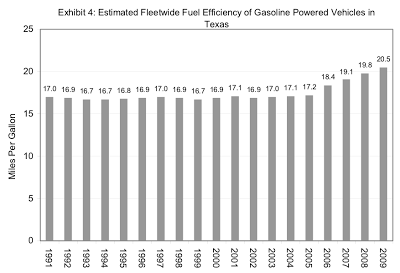

Part of Dr. Ellis’s conclusion is based on the theory that vehicle fuel efficiency is increasing much faster than probably is the case. While it is true that the U.S. has been using a lot less petroleum since 2007, this is probably in large part due to the fact that the public driving is less.

The reality is that while average vehicle fuel efficiency is really increasing, it is only happening very slowly. It takes about 10 years for fuel efficiency to increase by 5%, or .5% per year, largely held back by a slow vehicle replacement rate, as Stuart Staniford shows in this chart.

In sharp contrast to this probable rate of vehicle efficiency increase, Dr. Ellis estimates in his chart that vehicle fuel efficiency in Texas has somehow increased from 17.2 MPG in 2005 to 20.5 MPG in 2009 (see Exhibit 4 of his report). This would be a whopping 19% vehicle fuel efficiency increase in just over four years. This is nearly 5% a year, or almost 10 times the much more plausible rate of .5% a year seen above.

Exaggerating the probable increase in fuel efficiency helps the road lobby ignore the current and ongoing stagnation in vehicle miles of travel since the 2007 peak, both in Texas and the USA. The theory seems to be that any time now we will dump our old cars and go out and buy new electric cars, which the road lobby will tax per mile with road user fees. Meanwhile, we are expected to keep driving more and more, just as we did in past decades of cheap oil.

Texas roads are already deteriorating on a large scale

With the Texas road lobby in effective political control of state funding, most of the available road money has been going into building new roads. As they say, there are no ribbon-cutting ceremonies for maintaining existing roads, which in Texas have been deteriorating. As this piece points out, Texas road upkeep is getting lot more expensive, so repairs are falling behind to the point that most Texas roads are in now less than good condition.

Texas’ road conditions

As of 2008, a full 65% of Texas’ state-owned major roads had fallen out of good condition, meaning they will now be increasingly expensive to repair and maintain. Only 34% of Texas’ roads were in good condition, the state in which repairs are least expensive. The condition of 1% of Texas’ state roads was not reported.

Texas’ highway spending priorities

Between 2004 and 2008, Texas spent 62% of its highway capital expenditures on road expansion – $4.1 billion each year on average — but only 11% on repair and maintenance of existing roads — $692 million. That 62% of spending on expansion added 2,962 lane-miles to the Texas road network.

Texas would need to spend $4.5 billion annually for the next 20 years to get the current backlog of poor-condition major roads into a state of good repair and maintain all state-owned roads in good condition. Shifting more funds toward repair would go a long way toward addressing the state’s maintenance needs.

The Texas road lobby’s funding solution:

the Mileage-Based User Fee (MBUF)

Given the TTI’s faith in the need to build more roads to accommodate an ever-increasing level of road demand, combined with an increasing inability of the fuel tax to meet the funding gap, it is easy to conclude that a lot more road funding revenue will be needed.

Anything to avoid seriously dealing with the basic need to shift transportation policy toward more energy-efficient compact urban development sometimes called smart growth, together with a new focus on public transportation.

The road lobby’s basic conclusion is that Texas now needs to move toward some kind of vehicle mileage tax or fee, and raise a lot more money per vehicle mile driven. However any kind of new tax or fee that extracts more total money from already financially stressed drivers is going to be widely unpopular. Since the word “tax” is already quite unpopular in Texas, other terms are being used such — as a “Mileage-Based User Fee.” Alternative terms being used are “road user charges” or “network tolls.”

A new tax or fee on miles driven is seen as one of the few possible ways to raise enough new money to keep the road-building game going. However this method of funding expanded road capacity ignores the effect that rising fuel prices are having by already reducing total per capita driving. It is becoming a matter of what the driver market will bear, given that driving is now in decline both nationally and in Texas due to the rising cost of fuel on top of a stagnant economy. But TTI sees little alternative.

TTI Leads Mileage-Based User Fee

Conference, June 20, 2011

Some 115 federal, state and local government representatives, transportation system users, private-sector representatives, and transportation researchers attended the Symposium on Mileage-Based User Fees (MBUF) in Colorado, June 13-14. That represents a 60 percent increase over last year’s attendance.

MBUFs, also known as vehicle miles traveled (VMT) fees, would raise funds based on how many miles a motorist drives. Revenue generated would replace or supplement the inadequate fuel tax, which comes from each gallon of gas sold at the fuel pump.

“Although the idea of a road-user fee to replace or supplement the fuel tax has been discussed and researched at varying degrees for about a decade now, interest is really growing at the state and national levels,” says symposium co-chair Ginger Goodin, of the Texas Transportation Institute (TTI). Goodin is currently serving as principal investigator for a USDOT study on road-user fee collection technologies and is TTI’s resident expert on the topic.

The Texas Transportation Commission (TTC), at its Dec. 15, 2010 meeting, took a look at a variety of road user fees in a presentation given by TTI.

The Texas Transportation Institute reviewed its draft report, “Is Texas Ready For Mileage Fees?” which asserted that fuel consumption will continue to decrease and make a gas tax an unsustainable revenue generation method in the upcoming decade.

This fact — combined with increasingly fuel-efficient and alternative-fuel vehicles and the $315 billion in funding needs for Texas transportation identified by the Texas 2030 Committee — demonstrates the inadequacy of the fuel tax as a viable long-term funding mechanism for maintaining and expanding highways in the Lone Star State,

the report read.

The Legislature required Transportation Commissioners to take a look at the viability of a Vehicle Miles-Traveled (VMT) tax, which would rely on either on-board devices or remote-tracking systems to measure the number of miles each registered vehicle travels, and then tax vehicle owners accordingly. No formal action was taken.

As a part of their background preparation for the TTC, TTI had set up a number of focus groups with average citizens to try to anticipate public reaction to road user fees. As the reader may easily imagine, new road user fees proved to be quite unpopular — “negative reaction to mileage fees heard raised were pretty consistent across the focus groups”

Even though different focus groups in different areas all had these concerns (privacy, cost, and enforcement), in some groups privacy was more prevalent and in other groups it was cost.

Where is the Texas road funding deficit headed from here?

Given the current political climate and budget constraints, the chances of the Texas road lobby actually implementing the proposed mileage taxes or fees seems highly unlikely. This is simply because the amount of new revenue thought to be necessary would require the imposition of much higher user or driver fees than are now being collected through the current Texas gas tax. This totals about 40 cents a gallon, — about half state and half federal.

However, the federal portion of this funding is in trouble since the feds have long been spending beyond their means. It appears that federal road funding must now shrink dramatically.

The Highway Trust Fund, based as it is on gas tax revenues, is the main revenue source for state and local transportation funding, special programs, and MPO planning funds. The gas taxes bring in about $35 billion annually, explained Beaudry, but the feds have been spending about $27 billion more than that, drawing upon revenues from other sources.

The crux of the Congressional debate swirls around “House Rule 21,” which says they can’t spend more than they bring in (in gas taxes), which means cutting more than a third of the transportation bill. There is disagreement over three options — raise the gas tax, dramatically cut spending or find new revenue sources.

In essence, a new and less costly approach to maintaining urban mobility than road-building-as-usual is needed pretty soon. The economics of driving is likely to play out this way: we will probably see much higher oil prices by next year, with $4.50 a gallon gasoline now anticipated.

Goldman-Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and Barron’s issued reports last week forecasting that oil prices will be much higher next year because of a stagnant supply situation. Goldman is saying the Saudis do not have nearly as much reserve capacity as Riyadh and the IEA claim and forecast oil at $140 a barrel next year. Barron’s is talking about oil reaching $150 next spring with spikes to $160 and $170 a barrel. Gasoline will be in the vicinity of $4.50 a gallon.

Just try to imagine the political challenge of the road lobby trying to impose miles driven fees on top of these fuel prices! But even this situation will probably not be enough to break through the current public denial relating to the unsustainability of driving as we have in the past.

To really break through our denial it may take $10 a gallon gasoline, as prominent peak oil policy analyst Tom Whipple has recently speculated:

Even weeks of 100 degree temperatures or even $4, $5, or $6 gasoline is unlikely to shift many prejudices in the short term. It is going to take a more severe shock — say food shortages or $10 plus gasoline — to shake the notion that a return to life as we knew it is still possible.

[Roger Baker is a long time transportation-oriented environmental activist, an amateur energy-oriented economist, an amateur scientist and science writer, and a founding member of and an advisor to the Association for the Study of Peak Oil-USA. He is active in the Green Party and the ACLU, and is a director of the Save Our Springs Association and the Save Barton Creek Association in Austin. Mostly he enjoys being an irreverent policy wonk and writing irreverent wonkish articles for The Rag Blog. Read more articles by Roger Baker on The Rag Blog.]