Texan Pennell, a ‘patron saint of American independent film,’ became his own worst enemy.

HOUSTON — Independent filmmaker Eagle Pennell had become somewhat of a permanent fixture in the bohemian Montrose bar scene after he moved to Houston from Hollywood in 1982. A creature of habit, he could be found parked on a bar stool any given night of the week at any number of the neighborhood watering holes. There, he held court all evening, talking about film and filmmaking to anyone who would listen and buy him drinks.

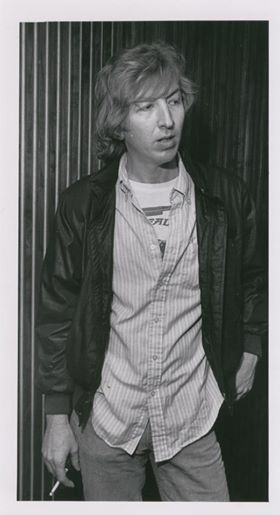

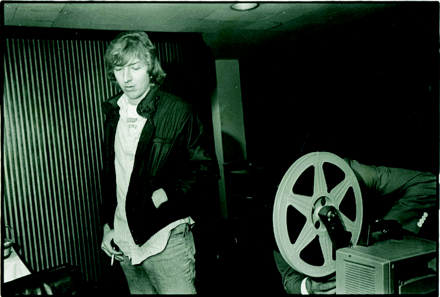

Not one to be burdened by personal possessions or leases imposed by landlords, Pennell preferred the life of a vagabond filmmaker. The tall, blonde, and charismatic Pennell was always on the lookout for a new benefactor with deep pockets to fund his next movie, or a new girlfriend with an apartment who could provide him with an alternative to the four walls of his rooming house.

Restaurateur and former Montrose resident Bill Sadler, owned The River Café in the early 1980s; it was a popular drinking establishment where Pennell was a regular. Sadler, who became Pennell’s friend and confidant, first met the filmmaker when he was shooting his second feature movie in Houston, Last Night at the Alamo.

The River Cafe was the hangout of choice for local artists during that era, and according to Sadler, Pennell was no exception. “Eagle even started getting his mail at the River,” Sadler said. Referring to Pennell’s excessive drinking, Sadler also recalled that he didn’t remember a time when the aspiring film director wasn’t “looped.”

“I barred Eagle for life at the River several times because of his drinking problem, but he always wormed himself back into my good graces.”

“We even got into a fist fight one night,” Sadler recalled. “We were talking about boxing and got into a friendly argument, and I thought he was kidding and then wham — he hit me. I boxed a little in college, and I laid him out on the floor of the restaurant, but we became better friends after that incident.”

Born Glenn Irwin Pinnell, Eagle cut his cinematic teeth shooting home movies.

Pennell was born Glenn Irwin Pinnell and raised in a middle-class family in the town of College Station where his father was an engineering professor at Texas A&M University and his mother was a travel agent. Like many other film directors, Pennell cut his cinematic teeth shooting home movies while growing up, using his father’s Super-8 movie camera and his three younger siblings as actors.

According to Internet folklore, Pennell reinvented himself while still a teenager, choosing the name Eagle because of his identifiable hook nose. He also modified his surname to Pennell with an “e,” a name that he borrowed from a character in the movie, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, a western made by his favorite director, John Ford.

The lanky, 6’4” Pennell, who was called “Big E” in high school, was known for his jump shot and for leading the Texas A & M Consolidated basketball team to victory on several occasions.

“That’s where I first saw him come into his own and display the power he had to control people and lead them on journeys, said Eagle’s younger brother, Chuck Pinnell. “He was sort of a celebrity on campus and that was probably both a good thing and a bad thing.”

Eagle Pennell moved to Austin after high school to study film at the University of Texas.

Eagle Pennell moved to Austin after high school in 1970 to attend the University of Texas to study film, but he became disillusioned with the academic side of filmmaking and dropped out in his junior year. Determined to make movies, Pennell personally financed and directed his first dramatic “short” at a cost of $1,500 while employed at Photo Processors, a film company located on South Congress in Austin and owned by the family of Lyndon Johnson.

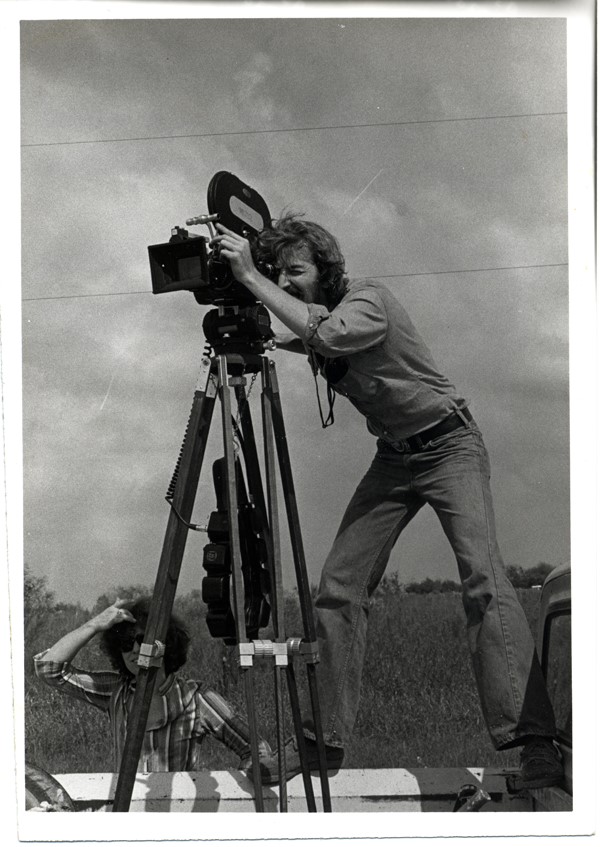

The 30-minute movie, A Hell of a Note (1977), was shot with borrowed equipment and local Austin actors, Sonny Carl Davis and Lou Perryman, were cast in the lead roles. At the time, Davis was better known for being one of the outlandish front men of Austin’s formidable, comedic rock ensemble, the Uranium Savages, and his sidekick Perryman, entered acting from a film production background; he was an assistant cameraman on Tobe Hooper’s original Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974). Hell of a Note was well received by the Austin film community, and word of the low-budget, black-and-white short eventually reached the attention of the late film historian and documentarian, James Blue in Houston.

Blue was the former director of Rice University’s media center and host of the local PBS television program, TEXPO, which featured the work of new and innovative young filmmakers. Blue was so taken with Pennell’s grainy, 16-millimeter narrative that he invited him to Houston to speak at the media center after the movie was screened on campus.

“James was very respectful of Eagle’s work and very encouraging,” said Brian Huberman, cinematographer and associate professor of film at Rice University. “When he [Pennell] came to Houston it was like visiting royalty which is why he chose to move here after living in Los Angeles. He was always well received here.”

Blue also helped Pennell secure financial support from the Southwest Alternate Media Project, Inc., a nonprofit media arts organization he co-founded in 1977 with Dominque de Menil, a philanthropist, art collector, and the heiress to the multi-national oilfield services dynasty, Schlumberger Limited. With multiple contributions from family and friends, the grant from SWAMP, and an investment from Texas high-stakes poker player and rare-book dealer, John H. “Austin Squatty” Jenkins, Pennell was able to realize his first feature-length film. The highly regarded drama, The Whole Shootin’ Match (1978), written by Pennell’s then-girlfriend, Lin Sutherland, and shot in Austin, featured local actors, Sonny Carl Davis and Lou Perryman again, plus ingénue, Doris Hargrave. The movie was completed with an estimated production budget of $30K, according to the Internet Movie Database.

‘The Whole Shootin’ Match’ was screened at the USA Film Festival in Dallas.

The Whole Shootin’ Match was selected to be screened at the USA Film Festival in Dallas, on the campus of Southern Methodist University, after its release. There, keynote speaker, film historian, and movie critic, Arthur Knight of the Hollywood Reporter, showered Pennell, cast, and crew with accolades, and told the attentive festival attendees, “what’s happened with this film is something that I feel is very important and is a phenomenon that is just beginning to happen,” referring to the do-it-yourself, regional filmmaking for which Pennell would be known.

“We’re so used to movies coming from Hollywood and New York that we forget that there is a great section of the country still to be heard from. It seemed to me that here was a story that was recognizably Texas, and recognizably Texans, and they were able to tell us something about a way of life for those of us who live in various parts of the country would be of far more interest than if it had been told by somebody who discovered Texas out of American International,” a reference Knight made to the low-budget, Hollywood studio where cult director Roger Corman rose to prominence.

“And that is why I was so eager for the film to receive its premiere here in Dallas,” Knight said. “And Eagle — I can only congratulate you for what you’ve done.”

The Whole Shootin’ Match was also selected to be screened at the U.S. Film Festival (now rebranded the Sundance Film Festival) in Salt Lake City, where it received a “special” second-place prize from the film jury.

Pennell, however, was his own worst enemy, a personality trait that kept him from achieving and maintaining any level of success.

He would destroy any great opportunity

that came his way.

“Eagle was so self destructive. He would destroy any great opportunity that came his way or find a way to mess it up and I witnessed it over and over again,” said his friend Bill Sadler. “He had demons inside him. He burned a lot of bridges. Eagle was a good filmmaker but not a good businessman.”

With the positive reception of his first feature film, Pennell was given the opportunity to test his cinematic prowess and make a name for himself in Hollywood in the form of a “development deal” from Universal Studios. Fortuitously for Pennell, Verna Fields, then-vice president in charge of production, was a member of the film jury at the Utah festival where his movie was screened. He and his new co-conspirator, Kim Henkel, screenwriter of the Texas Chainsaw Massacre, left for California to take Fields up on her offer to develop a story treatment and the first draft of a shooting script in exchange for a small retainer. However, after a period of time in Los Angeles, Pennell and Henkel managed to squander their advance, and the much anticipated script never received a green light from Universal’s production department.

“They had a working title, The King of Texas, and not much else,” recalled Chuck Pinnell, an Austin-based musician and composer who scored the music to the majority of his brother’s movies. “It was kind of meandering and not particularly compelling. There’s a copy of it in the Wittliff Collections at Southwest Texas [now Texas State University] in San Marcos. As I recall, they got a $5,000 advance that he and Kim spent carousing down in Boy’s Town [Nuevo Laredo]. Frankly it wasn’t a very inspired work, and I wasn’t surprised that Universal lost interest in it.”

“The whole thing pissed me off supremely, Pinnell reflected, ” it was a giant missed opportunity. Just something that Eagle talked his way into and couldn’t deliver on.”

After his experience with corporate Hollywood, Pennell moved to Houston.

After his experience with the constraints of corporate Hollywood, Pennell moved to Houston where he felt he was more appreciated. There, he was able to raise enough venture capital, including a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, to make his second independently produced, DYI movie, Last Night at the Alamo (1984). The film was shot using the same ensemble cast as before: Davis, Perryman, and Hargrave, plus Pennell’s younger sister, Peggy Pinnell. However, this time they used a Houston film crew.

The screenplay, written by Henkel, was a more cohesive and polished narrative than the previous co-write with Pennell, with humorous and relatable characters, similar to Pennell’s first full-length feature. Henkel also co-produced and even co-directed the film when Pennell fell off the wagon and was unable to maintain his focus. The movie received glowing reviews and is regarded to this day as a “definitive example of independent regional cinema,” according to author and film historian, Alison Macor. The IMDb website estimates the production budget to be $25,000 which was the sum Pennell received from his NEA grant.

Last Night at the Alamo was screened at the New York Film Festival, the Sundance Film Festival, where it received a special jury prize in the dramatic category, and at the USA Film Festival where Pennell’s first feature film was so well received.

“I remember when Last Night played at the Dallas [USA] Film Festival in 1984. The night it premiered was right before they showed the Coen Brother’s first feature movie [Blood Simple]. We were all hanging out after the screening and as I was looking at them [Joel and Ethan Coen], I realized we were not going to make it like these guys were going to make it,” Pennell’s younger brother somberly reflected, “they clearly had their shit together.”

Academy Award-nominated director and ex-Houstonian, Richard Linklater, has always professed that Pennell was a big inspiration on his own movie-making career. In an interview conducted by Pennell’s nephew, documentarian Rene Pinnell, Linklater referred to Pennell as “one of the patron saints of American independent film.”

“I first heard of Eagle at that great moment in my life when I was first discovering film,” Linklater said. “And I was just at that point when I thought, well maybe I can make a film. And I went to see this low budget local film. It was magnificent. Looking back, it was a big moment in my own film evolution just because it gave me a lot of encouragement. Here was a guy, who with not much money, made a film that really spoke to me.”

When reviewing Last Night at the Alamo for the Chicago Sun-Times the year it was released, the late film critic Roger Ebert wrote, “I love this film. It’s one of the funniest, saddest, and touching slices of Texas life I’ve ever seen, with an ending worthy of Eugene O’Neill. This is one of the best American films of the year.”

However, what was subtly apparent to cast and crew during the production of Pennell’s second feature movie, reached full-blown fruition by the film’s completion.

‘Drinking is what he became more and more interested in towards the end of his life…’

“Drinking is what he became more and more interested in towards the end of his life, and less interested in making movies,” said Brian Huberman, cinematographer on Last Night at the Alamo, “because sadly — he was an alcoholic.”

By the mid-1990s, after making two more movies in Houston, Pennell had finally exhausted all possibilities for any future success. Both of these features, Heart Full of Soul (1990) and Doc’s Full Service (1994), were looked upon as possessing less than compelling story lines and more than forgettable dialog compared to his first two feature-length movies. After viewing Doc’s Full Service, Louis Black, film critic for the Austin Chronicle, wrote: “it looked liked such a promising first feature but unfortunately it was the filmmaker’s fourth or fifth.”

Pennell was now broke with no steady income or possible future employment; industry insiders and potential investors believed him to be “a bad risk.” He had also managed to alienate his friends and “girlfriends,” and was now surviving on the Houston streets.

“I remember on one occasion Eagle shoplifted a sirloin steak from the Fiesta supermarket in Montrose,” said Houston singer/songwriter Kirk Farris who acted in both Heart Full of Soul and Doc’s Full Service. “He stood outside the nearby King Cole liquor store on Richmond Avenue trying to sell the steak to people as they entered the store so he could make enough money to buy his next drink.”

According to a 2016 report by the Houston Coalition for the Homeless, and based on a “point in time count,” there are 3,626 homeless adults, sheltered and unsheltered, on the Houston streets at any given time in Harris and Fort Bend counties. In a similar study conducted by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, and contrary to popular belief, alcohol and substance abusers account for only 9% of these itinerant individuals. Loss of employment and therefore, the means to acquire and maintain affordable housing, comprises the largest segment of Houston’s homeless at 35%. Individuals with mental health disabilities, the study revealed, account for only 10% of the chronically homeless. To the untrained eye, this last segment of society would appear to be more endemic in Houston’s urban landscape than what hard data has shown.

Unfortunately for Pennell, he fell into the segment of the statistical pie made up of the aforementioned 9% of Houston’s homeless who were in that condition due to alcohol and substance abuse.

Pennell stubbornly admitted defeat and checked himself into the Houston Men’s Center.

By 1999, with monetary assistance from his family, Pennell stubbornly admitted defeat and checked himself into the Houston Men’s Center (now known as the Recenter) in order to curb his ongoing destructive addiction.

The Recenter, located on Main Street, is a nonprofit, residential treatment facility that has been in operation since 1950. They treat two of the root causes of homelessness, alcoholism and drug use, with counseling and a 12-step recovery program for those who choose sobriety.

Pennell, however, never followed through with the Recenter’s recovery program, and after six months, he was back on the streets of Houston. Unshaven and dirty, Pennell was seen panhandling for money on street corners and sleeping in neighborhood parks and under freeway overpasses.

“Rehab is for pussies,” Pennell told Brian Huberman when he asked how his recovery was going.

“The last time I saw Eagle,” said Huberman, “was outside the laundromat that used to be at the corner of Stanford and Hawthorne streets in Montrose. He was clearly drunk, hanging out, wearing an oversized cowboy hat and just panhandling. He had a horrendous black eye that I asked him about and he just laughed.”

Pennell was remorseful toward the end of his life.

Pennell was remorseful toward the end of his life regarding his behavior and the effect it had on his career and his relationships with others, according to Huberman. He longed to change his lifestyle and maintain his sobriety, and resume his life of making movies.

However, on the morning of July 21, 2002, Houston paramedics found Pennell dead on the living room floor of a friend’s apartment in a brick duplex located on West Main Street in Montrose where he had crashed the night before. The autopsy, performed by the Harris County Medical Examiner, ruled that his death was an accident and that the cause was both “acute and chronic ethanol toxicity.” Eagle Pennell died homeless and penniless just one week shy of his 50th birthday.

“I recently ran across a photo I had of Eagle and I said to myself, ‘What a striking looking guy’,” Huberman reminisced. “He had a real star-like quality, and for a brief moment in time — he climbed on the shoulders of all those around him and he was a star, and it was wonderful and everyone loved him — and then it was all over.”

At the conclusion of the 2011 movie Bernie, a feature based on a “stranger-than-fiction” crime story first published in Texas Monthly magazine that starred actors, Jack Black and Shirley MacLaine, director Richard Linklater paid homage to Pennell and the late character actor, Lou Perryman. As the closing credits crept up the screen in boldface font, those moviegoers who chose to remain in their theater seats until the very end of the movie were treated to the following message: In remembrance of Lou Perryman and Eagle Pennell — you guys were with us on this one.

Find more articles by Ivan Koop Kuper on The Rag Blog.

[Ivan Koop Kuper is a freelance writer, real estate broker, and professional drummer in Houston. He can be reached for comment at kuperi@stthom.edu.]

Great stuff, Koop. I gotta admit that Eagle mooched a few drinks off me at the Hole in the Wall. He could definitely spin an entertaining story for the price of a shot.