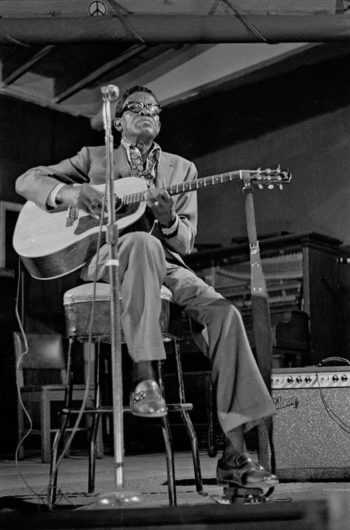

His appearance on Austin City Limits was a highlight

of Lightnin’s career.

HOUSTON — Texas blues legend Samuel “Lightnin’” Hopkins was 66 years of age in 1978, when he was booked by television producer Terry Lickona, to be included in the fourth season of the nationally syndicated PBS TV program,” Austin City Limits.” The idea to have Hopkins perform was pitched to Lickona by Ron R. Wilson, Hopkins’ bassist who, at age 23, was elected to the Texas State Legislature the prior year. Also, inconspicuously on board for the taping to fill out the rhythm section was Austin drumming luminary, William G. “Bill” Gossett.

“That was the year we began to branch out from the show’s roots of ‘Texas Progressive Country’,” said Lickona from his office in Austin. “When I was promoted from assistant producer to producer, I just wanted to stir things up a little bit. Lightnin’ was a Texan, but not quite like the other musicians that had been previously booked on the show in its early days.”

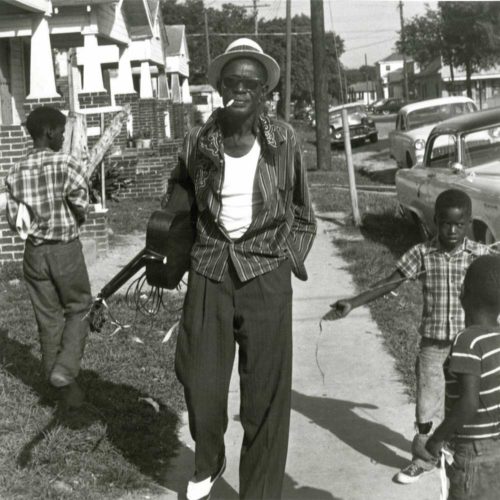

The engagement would be one of the highlights of Hopkins’ career; a career that spanned more than 35 years beginning in 1946, when he moved away from his hometown of Centerville, Texas, to the segregated inner-city Houston neighborhood of Third Ward. Once considered to be the epicenter of African-American business, politics, and culture, it was where Hopkins now called home and where he was celebrated by his friends and neighbors as the cultural icon he had become.

Houston’s Third Ward is where Hopkins

performed regularly.

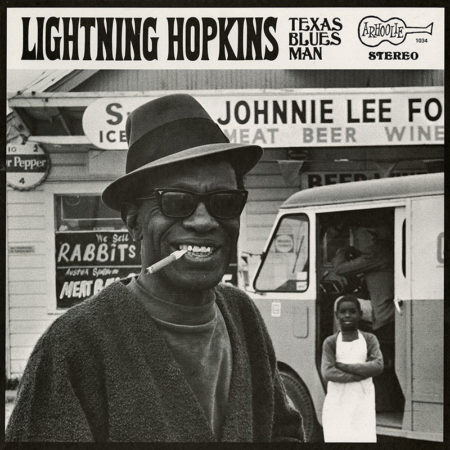

Third Ward is where Hopkins performed regularly at Irene’s Bar, the Showboat Lounge, and the Sputnik Café; where he held court in front of Johnnie Lee’s Chinese Grocery; where he shot dice with his cronies in the back of Shorty Calloway’s Auto Shop; and where he drove through the streets in his black 1977 Cadillac Coup de Ville, to and from the Chateau Orleans Apartments located at 3124 Gray Street.

“I had been dealing with Ron Wilson for this booking; he was my contact,” Lickona recalled, “and I think he was just as keen to make that show happen so he could also be on stage in front of the TV cameras himself, in addition to getting Lightnin’ up there. He was sort of the liaison between Lightnin’ and the show.” Lickona confided that being from Poughkeepsie, New York, he had never seen Hopkins perform and if it was not for Wilson, the engagement would never have happened. “I believe that playing behind Lightnin’ on ACL was one of the proudest moments of Ron’s career,” Lickona added.

Hopkins was from the generation of post-WWII African-American country blues musicians who came of age in the height the Jim Crow era in the American South. He was the son of a cotton farmer who was raised in a part of the world — rural Northeast Texas to be exact — where time had stood still since Reconstruction. This was the pre-Civil Rights era when southern Blacks were marginalized with limited educational, employment, and fair housing opportunities; an era of systemic segregation and rampant racism; of voter suppression and poll taxes, and an overall inability to get ahead in the white man’s world.

Hopkins would remain suspicious of the ‘white man’ throughout his lifetime.

As a result of his generational disenfranchisement, Hopkins would remain cautious, suspicious, and generally untrusting of the “white man” throughout his lifetime — especially when it came to the business of music. This suspicion and distrust became more than apparent the afternoon before Hopkins was scheduled to tape his ACL segment in front of a live studio audience. This is when Lickona received a visit from bassist Wilson, informing him that in addition to a bottle of his favorite beverage, Hopkins requested to be paid in cash before the show or he would not go on that evening.

“I distinctly remember that October 9th was a Sunday and all the banks were closed,” Lickona reminisced. “We planned on writing him a check that he could cash on the following Monday,” referring to an era before the advent of ATMs. “I literally took a collection from our staff and crew to come up with the money [$400] that Lightnin’ requested and we also managed to find him a bottle of Jack Daniels. But from what I remember and in spite of everything that went down,” recalled Lickonka who is now at the helm of ACL and holds the title of executive producer, “Lightnin’ put on a great show that night.” Austin City Limits is currently celebrating its 45th season on the air making it the longest-running music series in the history of American television.

When Hopkins finally arrived at the KLRU studios for his performance, he was ready to shine for the occasion — and shine he did. He was decked out in his 1970s finery that included a cobalt blue polyester leisure suit adorned with sequin letters “L” and “H” affixed to each side of his chest. He was also sporting a light gray felt fedora that he wore cocked to one side of his head and he was wearing amber sunglasses.

For this auspicious occasion, Hopkins left his customary Gibson J-50 acoustic guitar at home and brought his brand new black, solid body Fender Stratocaster. To the delight of the audience, when Hopkins smiled after each song he performed, he revealed a front row of gold teeth that reflected the key lights that hung from the lighting grid in the original studio 6A, in the rusty communications building, on the campus of the University of Texas.

A shameless self-promoter, Hopkins was fond of creating his own mythology.

By the time the ACL program aired for broadcast in 1979, Hopkins could boast that he had performed in Canada, Japan, Mexico, in most of Europe, at the Fillmore Auditorium in San Francisco, and twice at Carnegie Hall in New York City. A shameless self-promoter, Hopkins was fond of creating his own mythology about his life and musical career, and was known — on occasion — to share the story of when he allegedly performed for the royal family: “When I played a command performance for the Queen of England, I said, ‘Queen Lady, I’m sure glad to meet you and if you just sit down over there, you’ll hear something you ain’t never heard before.’ And so I backed up and sat down on a stool and hit that first note so hard — you could hear it clean across the water.”

Hopkins was at the top of his game the evening of the ACL taping and was filled with confidence in addition to his favorite bottled spirits. After receiving an enthusiastic reception for one of the standards he always included in his repertoire, he proudly exclaimed, “Ladies and Gentlemen, it’s just really sweet to be here tonight. And you know, where you come from — well, that’s your name. And tonight, my name is Centerville, Texas — that’s where I come from.” Hopkins was in a nostalgic mood that evening and he wanted the audience to know exactly where he began his life’s journey.

Halfway through his ACL performance and to the surprise of the KLRU staff, Hopkins stopped the music and addressed the studio audience. “Thank you ladies and gentlemen. Alright, I’ve got something to tell you,” he said. “See, this here is the roots. You know — this is the roots.” Hopkins then went into an unscheduled commentary that at times could be construed as almost mystical bordering on the supernatural.

Hopkins attempted to explain and give meaning to the origin of the blues.

Hopkins attempted to explain and give meaning to the origin of the blues; he also spoke about his sister Alice and the visions she had of a past she never knew. Hopkins shared with the studio audience the fact that his grandfather was a slave, and how his father, Abe Hopkins, was murdered in Leon County, Texas, in a gambling-related incident, and how his murder was wantonly made to look like a suicide.

“I visibly remember that digression,” Likona recalled, “and in the control room, we were all wondering where he was going. But what he was saying just went right over all our heads. The whiskey definitely helped loosen him up and he was definitely in a chatty mood that night. It was one of the rare opportunities to hear Lightnin’ speak historically about his life and his family.”

Unrehearsed and seemingly unintelligible at times, Hopkins concluded by revealing to the mostly white Hippie audience members, “But the reason I’m tellin’ it is because I’m here on this television tonight and may not never get another chance to speak this word again — and I’m telling the truth.” Needless to say, the spontaneous and rambling tirade from Hopkins in the middle of his performance never made it to the final cut for broadcast, and to this day it still remains in the ACL archives.

Not long after Hopkins’ appearance on ACL, then-mayor of Houston, Jim Mc Conn, issued a proclamation declaring June 20, 1979, “Lightnin’ Hopkins Day.” This event transpired the day after Houston’s annual Juneteenth celebration which commemorates the day Union soldiers landed in Galveston, on June 19, 1865, with news of the end of the Civil War and with news of the emancipation of Texas slaves — two and a half years after the fact.

He was invited to headline Houston’s

Juneteenth celebration.

After taking part in a parade down Dowling Street (now Emancipation Avenue) in his beloved Third Ward, Hopkins performed at the annual Juneteenth Blues Festival at Miller Theater, in Houston’s Hermann Park. He was invited to headline Houston’s Juneteenth celebration the following year with other local music notables, including jazz tenor saxophonist Arnett Cobb and blues guitarist Rocky Hill.

Ron Wilson was introduced to Hopkins by his political mentor, the late United States Congressman and humanitarian, Mickey Leland. Leland represented Texas’ 18th District, a congressional seat held previously by Houston’s Barbara Jordan. When Wilson was still an undergraduate at the University of Texas, he was an intern for then-State Representative Leland, before his run for Congress. It was at Leland’s insistence in 1976, that Wilson pursue a soon-to-be vacant seat representing Houston’s 131st district in the Texas House of Representatives.

Wilson represented his predominately Black and Hispanic constituents in the Texas Legislature from 1977 until he was unseated in 2004. While he served in the Texas House of Representatives, Wilson continued to perform and tour with Hopkins, until the time when Hopkins was forced to take a respite from his live music activity in late 1981, due to ill health. Wilson still resides in Houston where he practices criminal and entertainment law.

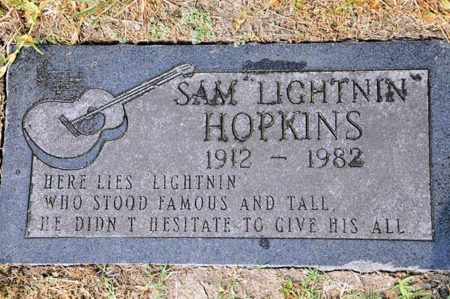

Upwards of 1,000 mourners filed past the open casket.

An assortment of family, friends, fans, musicians, and politicians attended Hopkins’ memorial service, held three days after his death on January 30, 1982, from pneumonia in his last stage of esophageal cancer. Marty Racine of the Houston Chronicle reported: “Upwards of 1,000 mourners formed a line around the block at Johnson’s Funeral Chapel in Third Ward in order to file past the open casket and pay their final respects to the Houston country blues singer-songwriter.”

Guitarist Rocky Hill even brought a resonator guitar and gave Hopkins his own personal sendoff with a slow, bottleneck version of “Amazing Grace.” This impromptu musical performance was met both favorably and with disdain from some of the attendees at what was described by Racine as a “quiet and low-keyed event.” Hopkins was known to tell young guitarists who attended his performances in an attempt to learn his technique and absorb some of his “mojo,” “When I’m gone, you’ll only have my records to teach you how to play the blues.” Hopkins was laid to rest at Forest Park Lawndale Cemetery in East Houston.

Fast forward 21 years after Hopkins’ death to the evening of February 13, 2013. It was there at the Staples Center in Los Angeles, California, during the broadcast of the 55th Grammy Awards, that Samuel “Lightnin’” Hopkins posthumously received a “Lifetime Achievement Award” from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. According to NARAS, a 501(c)(3) non-profit, “this award is presented to performers who, during their lifetimes, have made creative contributions of outstanding artistic significance to the field of recording.”

One could only speculate that, had Hopkins been alive to accept his award, he would have stepped up to the microphone and with a big grin exposing his front row of gold teeth, he would have confidently said to the Los Angeles music industry moguls and Hollywood sophisticates in the audience, “Ladies and Gentlemen, it’s just really sweet to be here tonight. And you know, where you come from — well, that’s what your name is. And tonight, my name is Centerville, Texas. That’s where I come from.”

[Ivan Koop Kuper is a freelance writer, real estate broker, professional drummer, podcaster, and an frequent contributor to The Rag Blog. Visit him online on Twitter and Instagram: @koopkuper.]

- Read articles by Ivan Kuper about Huey P. Meaux, Michael Condray, Eagle Pennell, Stacy Sutherland and Bunni Bunnell, Don Sanders — and more — on The Rag Blog.

Back in 1975 I went to see Lightnin’ Hopkins at the Armadillo. As usual, parking was sparse at the AWQ; we pulled into an adjoining dirt parking lot which specifically said there was no parking for the Dillo. I parked next to an older sedan; there was a guy sitting in the front passenger seat sipping on a pint bottle. Holy Moley, it was Lightnin’ Hopkins! “You’re Lightnin’ Hopkins!”, I exclaimed.

“I’m about to be,” he replied. Made my decade.

This piece reminds me of another reason why it was such a privilege to live in Austin: the Blues. From Janis on down, Austin has been full of white folks who understand the blues and learned to play well. How did they get so good besides technical mastery of their instruments? Freddie King, Albert King, B.B. King, Mance Lipscomb, Sonny Terry, Brownie McGhee—all of these folks played the hippie venues in Austin, and many is the lick that got stolen but mostly what happened was good-natured sharing. (Mance Lipscomb’s guitar got stolen, too, but that is another story I’ll let go beyond mentioning that Austin musicians put on a benefit to buy a fine new guitar for a fine old bluesman.)

How did those old guys learn the blues? By drinking the same water (and whiskey) as Huddie Ledbetter had.