Mass shootings of the innocent are commonplace now. But Charles Whitman, the Texas Tower sniper, shocked the nation’s psyche.

With introduction by Thorne Dreyer

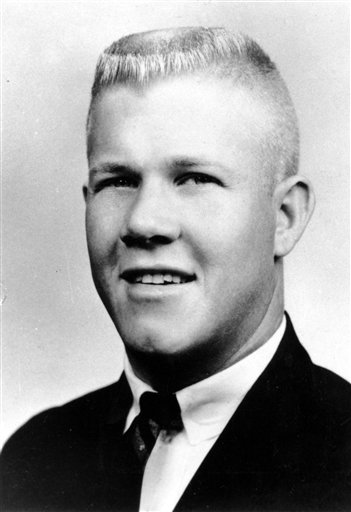

On August 1, 1966, 25-year-old engineering student, Eagle Scout, and former Marine sharpshooter Charles Whitman murdered his wife and mother and then took three rifles, two pistols, and a sawed-off shotgun to the observation deck atop the iconic Texas Tower at the UT-Austin administration building and for an hour and a half mowed down students and random pedestrians on the grounds below, killing 14 and wounding 32 others. Among those injured were our dear friends and colleagues Sandra Wilson and Claire Wilson (no relation), who lost her unborn child and her fiancé. Claire was saved by John Fox, Austin personality and musician now known as Artly Snuff, who, along with James Love, carried her to safety.

In her 2005 oral history of the shootings, Pamela Colloff wrote, “The crime scene spanned the length of five city blocks . . . and covered the nerve center of what was then a relatively small, quiet college town… Hundreds of students, professors, tourists, and store clerks witnessed the 96-minute killing spree as they crouched behind trees, hid under desks, took cover in stairwells, or, if they had been hit, played dead.” Coloff, as cited by Texas Monthly, wrote that Whitman “introduced the nation to the idea of mass murder in a public space.”

Keith Maitland’s Tower, which Variety calls “A tense, reflective and uniquely cinematic reconstruction of the 1966 sniper shootings that rocked a Texas university campus,” won two major awards at the 2016 SXSW Film Festival. Claire Wilson and Artly Snuff are prominently featured in the film.

The University of Texas has done little over the years to remember the victims of Charles Whitman but, thanks to the continuing efforts of survivors of the shootings, the university will dedicate a memorial to the tower victims on August 1, 2016, the 50th anniversary of that horrific summer day in Austin. It will be a large stone cut from Fredericksburg granite, with the names of all 16 victims etched into it. It should be noted that August 1 will also be the date that Texas’ campus carry law is set to go into effect. As Congressman Lloyd Doggett puts it, “There is cruel irony in our state authorizing guns on campus on the very anniversary of this tragedy.”

The article below, written by Jeff Shero (now Jeff Nightbyrd) was published by New York’s Village Voice on August 11, 1966. Jeff, who worked with the original Rag and edited RAT in New York and the Austin Sun, remembers: “I was there, much less heroic, keeping my head down. But I did write the following story that was once included in a list of the Ten Best in Village Voice history.”

— Thorne Dreyer, Editor, The Rag Blog

![]()

Vol. XI, No. 43 • New York, N. Y. • Thursday, August 11, 1966

Vol. XI, No. 43 • New York, N. Y. • Thursday, August 11, 1966

Deep in the Heart of Texas: The Guns of August

By Jeff Shero / The Village Voice / August 11, 1966

[Mass shootings of the innocent are commonplace now. But Charles Whitman, the Texas Tower sniper, shocked the nation’s psyche. He was the first killer in modern times to express his delusions by murdering those without fault. — Jeff Shero Nightbyrd, March 2016.]

AUSTIN, Texas — On the observation deck of the 27-story University of Texas Tower Cheryl Botts and Don Walden talked about their plans for the fall and about their panoramic view of all Austin. About 15 minutes before noon, they decided to leave and entered the receptionist’s room. The receptionist was gone. Cheryl nudged Don and, indicating a dark stain on the floor, said, “Don’t step on the ‘stuff.’” Don stepped over it, but his attention was focused on a man leaning over a couch on the other side of the room. The man picked up two rifles, turned, and stared at the pair. Don and Cheryl said “Hullo,” and he returned a hearty “Hi, how are you.” They continued through the room to the stairs.

Outside, students emerged from classroom buildings talking of grades and dates, most heading for the Student Union for lunch. The searing Texas sun reinforced the easy summer lethargy that the air-conditioned buildings and professors had tried to dispel. The heat shimmering from the concrete walks gave off a pleasant warmth in contrast to the overly chilled classrooms.

A girl crumpled on the University Tower steps. Most paid little attention, but a professor wondering if it was a psychological experiment testing people’s recall in emotional settings, hurried over to see if she was all right. In a pleading voice she begged, “Help me. Help me.”

To the west on the “drag,” the business street bordering the campus, students strolling in and out of stores began to fall. Several went down in front of the University Co-Op and Shefftal’s Jewelry, two more dropped 75 yards south at the YMCA, and, incredibly, a boy lurched from his bicycle more than 350 yards from the observation deck of the Tower.

Couldn’t Correlate

On the walks south and west of the Tower students began reacting to the clap of rifle shots reverberating off the buildings. There were moments of confusion as some clutched their wounds and fell to the pavement, while others dashed for the nearest cover and yelled to those who did not yet understand what was happening. Many knew the sound of a rifle report, but couldn’t correlate it with the people collapsing around them.

Trudy Minkoff stood in the English building screaming at people to come inside, that someone was shooting from the top of the Tower. People looked around, slowly comprehended what was taking place, and ran to the building. Some students who had dodged behind buildings and walls dashed out into the open to grab others who had collapsed. In the first few minutes many of those who instinctively attempted to rescue fallen students were coolly shot down themselves.

Shortly after noon, silence, save the sound of rifle shots, blanketed the campus. Both Trudy and a professor of English described the unrealness of standing impotently behind windows in the air-conditioned English building watching exposed people being shot on what was a main campus thoroughfare. Trudy said, “It’s funny, but I just didn’t see any blood. I just watched people being shot, and I never saw any blood even after they had lain there a long while. I guess I repressed it. It was like watching people killed on television.” The professor commented, “If it had been happening in Vietnam it would have been real death. But on the campus, it didn’t fit into any sense of reality. The window framed it like a picture, even though you knew it was actually happening.”

25 Square Blocks

Charles Whitman, the sniper, was God to the people below. He decided who lived and who died. All normal activity stopped. All attention was focused on him. No vehicles moved on streets that had been crowded with cars and motorcycles before. No person walked in the open. Charles Whitman controlled 25 square blocks. A man who strived all his life to be a success was in almost absolute control.

A wounded student lying on a walk moved, possibly toward cover, possibly in agony. Charles Whitman sent the additional shots that ended his life. An ambulance driver darted from the University Co-Op to rescue a suffering coed. A bullet from the Tower 150 yards away stopped him.

After almost a half hour police officers, students, and townspeople began shooting back at the sniper. Guns are common possessions in Texas. Students got them from their rooms, businessmen out of their stores. A student and policeman returned fire from the undergraduate library; three students shot from the Business-Economics building. An employee of the Great Western Smokehouse three blocks away unslung his deer rifle and fired at the Tower. When a policeman arrived he explained that he was a good shot and might be of help. Both continued firing.

Clouds of limestone continually burst from the sides of the Tower as a hail of fire was directed at the sniper. The sniper’s return fire was so rapid and from such differing directions that police speculated there might be two snipers. The siege of the Tower was ineffective. Whitman, instead of shooting over the thick stone wall, shot out of the drain slots and was virtually unreachable. The fire from the ground could serve only as a harassment.

Provided Time

The harassment did provide time to drag to safety many of the wounded. Teams of students would dash on to the malls, grab a victim, and scurry for safety. Later, one neatly dressed boy with glasses who had risked his life to bring in others explained in his rather high-pitched and Southern voice, “Those people were just lying out there and bleeding to death. I couldn’t just watch them. I had to do something.”

Like in the western movies, girls tore their slips for bandages for the wounded. But most of the rescued in the main campus area could not be gotten to ambulances. The ambulances, restricted to the streets where buildings provided cover, could not draw close enough to reach the victims.

Finally an hour and a half after it had begun, three policemen reached the top of the Tower and ended Charles Whitman’s life. The wounded, many who hadn’t gone into shock because of the hot sun, were gathered and hurried away on stretchers.

The battle was over. But people were not yet stunned by the carnage. Instead, with adrenaline-spurred curiosity, they surrounded the Tower to watch the stretchers with victims and hopefully the sniper carried out. For most, even the witnesses of death that noon, death wasn’t real. Crowding closer, watching the dying and dead brought out offered a better comprehension of the tragedy. Later in the Student Union people acted normally, sitting around tables discussing where they had been when the first shots were fired. The gruesome impact of 13 dead and 36 wounded did not set firmly until the following day.

Most Critical

The city hospital was like a battlefield station. Stretcher after stretcher was pushed into the building, filling corridors and spare rooms throughout the hospital. Doctors went searching among bullet-shattered debris to rush the most critical cases to the third floor operating rooms. A pregnant girl, Claire Wilson, wounded in the abdomen, was found in the first floor X-ray room and rushed to the third floor. Another girl shot in the chest died twice on the operating table, but was brought back each time. People with more minor wounds like Sandra Wilson who had been shot in the chest and had a deflated lung were given emergency treatment and held to that evening for operations. Soon, in the hall between the operating rooms and the intensive care unit, grieving parents pleaded with hurrying nurses to know the condition of their offspring.

The question which plagued every thinking person after the slaying was, Who is Charles Whitman? What motivated him to murder his wife, mother, and the many within rifle shot of the Tower during his hour and a half reign of terror? After casting about for excuses such as brain tumors, drugs, and extremist political leanings, it was admitted that Charles Whitman, community pillar, Eagle Scout at 12, Marine, honor student, and Scoutmaster, had mentally collapsed.

Psychiatrists analyzed him as schizoid, as an “anti-social psychopath” and talked in psychological terms about his love for his mother and hatred for his father. Others explained he had repressed his hostilities until he lost control and had to turn to functional normative systems to guide his behavior. Beginning with state officials’ observations and concluding with the Austin Grand Jury’s statement, the public was assured that “this could have taken place anywhere.”

Some Explanation

Yet one uncomfortably remembers the same “irrational man” explanation for the Kennedy assassination.

Undoubtedly mass murders can take place anywhere. But the fact remains that this mass murder took place in Austin, Texas, not Madison, Wisconsin, and that Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, not Cincinnati or Seattle. It is also true that America has the highest per capita violent crime rate in the world, and that Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio are among the leaders of major American cities in homicides.

America and its social scientists tend to deal with social aberrations such as alienation, homosexuality, or psychopathic murders as individual malfunctioning, European social science tends to deal more with social and historical causation. The American public is reassured that Charles Whitman and Lee Harvey Oswald (et al?) are deficient elements, but that nothing is amiss with Austin or Dallas or America.

It’s a most comforting viewpoint.

But even a superficial view tells us something is amiss. Clearly American males indulge in a fantasy world of violence which establishes masculinity and power over competitors. It’s not just that James Bond seduces lovely girls, but that his charm comes from his work — killing. Look at the recruiting brochures of the Green Berets if that sounds implausible. They headline over a display of exotic weaponry, “Be a Real Man.”

Most areas of the country lack the violent frontier traditions and the easy supply of weaponry so that fewer opportunities exist elsewhere to act out fantasies in violent ways. Texas, 40 years from its range days, lives with a thin veneer of urbanity. Here in Texas, guns are forbidden in university dormitories. One professor of sociology quizzed his class and found that three-fourths had guns in their rooms. Before President Johnson was to give a commencement address on the campus, the Secret Service took special precautions. In one dormitory several hundred hunting rifles were found. Charles Whitman carried to the observation deck of the Tower a 6mm Remington magnum rifle, a 35mm Remington rifle, a .30 caliber carbine, a sawed off shotgun, a 1.357 magnum pistol, a 9mm Lugar, and a small hand gun. The local Austin paper discussing these weapons headlined the article “Arsenal Ordinary in Texas.” Austin Police Chief Miles when asked about the number of guns is quoted as saying that the number Whitman owned is not unusual: “The only unusual thing is that he took them to the top of the tower.”

Contained Hostility

The accounts of Whitman’s personal life stress his striving for achievement and perfection, and his repression of hostility. His father notes how he strained to achieve a high grade point average. This we learn is not so much in a desire for knowledge, but to bring him closer to his goal – “to make money.” We can logically surmise that contained his hostility to be well thought of by his associates and professors.

The hostility that the psychiatrists and his friends describe was undirected. He did not have a world view with which he could conclude his troubles lay with the “Communists,” the “ruling elite,” or a university which enforced an educational system which alienated him. Unlike the Negro who has “the Man” on his back, or the peasant whose problems are derived from the “landlord” or “Imperialists,” Charles Whitman had no devil. With no precise enemies, his indiscriminate hostilities were nurtured.

Pressures Built

As the mental pressures built within him and led to a breakdown of normal processes, his surroundings shaped an outlet. In Texas, with the availability of guns and a Tower, that outlet was not knifing someone in the subway, rolling drunks, throwing Molotov cocktails at the police, or napalming the Viet Cong. It was to ascend the Tower and God-like snuff the life from the tiny moving beings below.

In the Student Union coffee shop a group of intellectually oriented students were sitting around a table discussing the events. They ranged from liberal Democrats to civil rights and peace activists to hallucinatory drug users. One fellow observed, “I’ve been up on the Tower, watched the people walking below, and imagined myself with a gun. It seemed so easy to plink people off. It gave me a peculiar sense of power.” There was a silence and after a short while he asked us if we had similar feelings while on the Tower. Of nin of us, all familiar with firearms, seven admitted to having imagined themselves with a gun.

The thought which dominates this massacre by Charles Whitman is that it is a too understandable development within Texas society. Instead of the act of indiscriminate murder being an extraordinary event, one must be surprised it doesn’t happen more often.

Read more Rag Blog articles by and Rag Radio interviews with Jeff Shero Nightbyrd.

[Jeff Shero Nightbyrd, who lives in Austin, was a leading figure in the ’60s New Left. He was national vice president of SDS and later was active with the Yippies. Jeff helped start Austin’s historic underground newspaper, The Rag, and was publisher and editor of RAT in New York and the Austin Sun. In recent years Jeff has run a major talent agency. He is currently working on a book featuring cartoons, photographs, and articles from RAT.]

Four years earlier, in 1962, a writer named Ford Clark in Iowa authored a book novel called “The Open Square.” It is about a guy who went up to a university tower and started shhoting people. He was interviewed by the Statesman during the week after Whitman’s rampage. No one knows whether Whitman read the book. But there are some awesome similarities. Used copies of the book are available online and I am reading it now.

What’s amazing about the article, and so sad, is its relevance in current times. How is it that we have learned nothing from the all the mass shootings, which continue to this day at fevered pace? This beautifully written article could have been written yesterday…or tomorrow.

Jeff’s piece passes the test of time.

Sad that a well-educated person like Jeff in 1966 could pretty much touch the bases that get touched every time the incident repeats 50 years later.

I suggest one reason for that is the NRA’s success in getting federal funding cut off for gun research. Can’t let those fuzzy thinking professors crunch those liberal-biased numbers, right? No telling what they might discover.

(That’s why we call it “research.”)