There’s hardly an important rebel who isn’t mentioned in the pages of Cottrell’s book.

SONOMA COUNTY, California — Robert C. Cottrell’s survey of radicalism in the U.S. in the twentieth century is a short, compact book that moves with great speed. It has to move swiftly to map the vast territory that it encompasses. From the Industrial Workers of the World, better known as the Wobblies — who organized men and women that other unions ignored — to Black Lives Matter and #MeToo is more than a hundred years.

That time period includes two world wars, the Great Depression of the 1930s, the rebellions of the Long Sixties that lasted from 1955 to 1975 and contemporary events like the Battle of Seattle in 1999 which ushered in a new age of protest for a new millennium.

Cottrell has made it his life’s work to study and chronicle the Sixties in books such as Sex, Drugs, and Rock ‘n’ Roll, though he hasn’t limited himself to any one decade.

A biographer as well as an historian, he has told riveting stories about the likes of I. F. Stone.

A biographer as well as an historian, he has told riveting stories about the likes of I. F. Stone, who edited and published I. F. Stone’s Weekly, a beacon of light in the dark days of Senator Joseph McCarthy and his chief counsel Roy Cohn, the subject of two recent documentaries.

He has also written about Roger Baldwin of the American Civil Liberties Union, who led the organization in the 1920s and 1930s when it fought censorship and blatant violations of the Bill of Rights during the trial of those two Italian-born anarchists, Sacco and Vanzetti, who became martyrs all over the world after their execution in 1927.

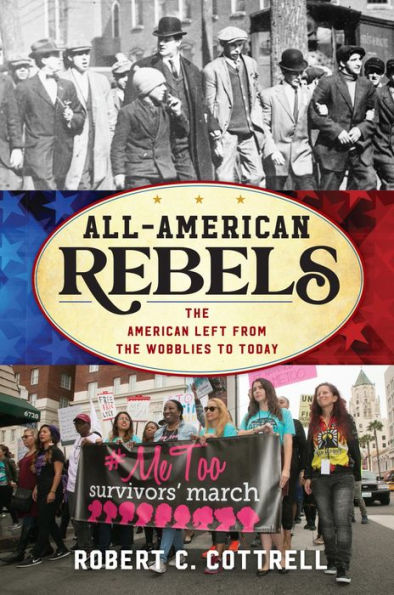

Many of the hundreds of historical figures who appear in All-American Rebels [Rowman & Littlefield, 2020, $36] were viewed as un-Americans by U.S. presidents, newspaper publishers and demagogues like Father Charles Coughlin who supported fascism and fascists on his popular radio show.

There’s hardly an important rebel who isn’t mentioned in passing in the pages of Cottrell’s book. Sometimes whole sentences are largely made up of names, as for example when he mentions more than a dozen supporters, including Gene Kelly, Arthur Miller, Helen Keller and Paul Robeson, of Henry Wallace who ran for president as the candidate of the Progressive Party in 1948.

Cottrell gives ample space to ‘The Rag’ and to radicals who appeared on Rag Radio.

Cottrell gives ample space to The Rag, The Rag Blog, Thorne Dreyer and to radicals who appeared on Rag Radio, including former SDSers — there’s another long list — such as Tom Hayden, Todd Gitlin, Bill Ayers, and Bernardne Dohrn.

The author also mentions little-known radicals such as the labor lawyer, socialist and suffragist, Inez Milholland Boissevain, who died at the age of 30, just four years before passage of the nineteenth amendment which guaranteed all women the right to vote.

What is both striking and predictable about Cottrell’s history is that it lambasts communists and the Communist Party of the United States for what the author calls “fealty” to the Soviet Union. No doubt about it, many American lefties (and not just Reds) were far too sanguine and far too uncritical about the U.S.S.R., especially under Stalin. What Cottrell doesn’t give enough credit to were the many rank-and-file CP members who were far more focused on what happened in Washington D.C. than in Moscow.

He also doesn’t sufficiently recognize that American CP members were more intensely opposed to racism and Jim Crow than members of any other significant lefty group in the U.S. in the 1930s and 1940s. Some of that was opportunist but not all of it. Reds like John Reed could also be idealistic.

Cotttrell faults the CPUSA for accepting ‘Moscow Gold.’

Cotttrell faults the CPUSA for accepting “Moscow Gold,” but doesn’t place that policy in the context of the Cold War, or mention in the same breath that the U.S. government funded right-wing groups and organizations around the world in the same time period. Why no mention of the role of the CIA in the cultural Cold War in Europe, which led Allen Ginsberg and others to cry “a plague on both your houses”?

The author seems too eager to tarnish people like the poet, Carl Sandburg, whom he calls a “courier” for “communist Russia,” and too determined to score points by parading public figures like Henry Luce who described Stalin as “Uncle Joe” at a time when the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. were allies in the war against fascism.

When he gets to Weatherman and the Weather Underground, Cottrell relies too heavily on the work of journalist Bryan Burrough, makes Bill Ayers the fall guy, and lets others off the hook who were equally responsible for glaring tactical and strategic errors.

He calls the Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm “brilliant” but insists that he “framed the communist world view… far too romantically.” One hundred or so pages further on, he uses the word “great” to describe the historian, E. P. Thompson, but doesn’t point out any of his flaws.

While he usually provides exhaustive lists of significant individuals, he neglects to mention Allen Young, a contributor to The Rag Blog, when he writes about the Gay Liberation Front, and he omits the name Huey Newton when he introduces the Black Panther Party which he writes was “headed by a couple of young men, Bobby Seale and Eldridge Cleaver.”

Cottrell is often too quick to bury movements and causes and write their epitaphs.

Cottrell is often too quick to bury movements and causes and write their epitaphs. The counterculture, he explains, had “fatal flaws.” Indeed, it did have flaws but many of them were not fatal. In significant ways, the counterculture of the Sixties, and the spirit of the theatrical, satirical Yippies, is still alive, albeit altered to fit the twenty-first century.

“The deaths of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy were simply crushing,” Cottrell insists, and doesn’t allow for rebounds and the resilience of civil rights activists who are still in the thick of the fight.

What saves the book again and again are the pithy quotations that the author unearths. So, he includes Jack A. Smith’s description of SDS as “more with Che than Fidel; more with Fidel than Mao; and certainly more with Mao, at least as a revolutionary figure, than Kosygin.” And there’s Frank Bardacke who noted of the radicals at Stop the Draft Week in Oakland in 1965, “we did not loot or shoot.”

There is much to learn from Cottrell’s book, including the author’s own inclination to demonize some and scapegoat others, which does no service to the historical record.

[Jonah Raskin is the author of For the Hell of It: The Life and Times of Abbie Hoffman just translated into French and published in France under the title, Pour le plaisir de faire la révolution.]

- Read articles by Jonah Raskin on The Rag Blog and listen to Thorne Dreyer’s Rag Radio interviews with Jonah.

Hmmmm . . . Maybe I will read it when it comes out in paperback, or to the library.

I appreciate your pointing out that “American CP members were more intensely opposed to racism and Jim Crow than members of any other significant lefty group in the U.S. in the 1930s and 1940s.” I’m not sure I can take yet another singling out of the CPUSA for its many flaws. It seems that the Cold War has never ended, and it’s still Russia vs. the good guys in the U.S.