Joe Grant, the publisher of ‘Prisoners Digest International,’ was one of the unsung legends of the underground press.

It’s always jarring to receive Facebook birthday reminders for friends who you actually know and love when you know that they died within the past year. September began that way for me.

Joe Grant was one of the unsung legends of the underground press. He was a dear friend and a hero. He also was a thief, a scoundrel, a hustler, a counterfeiter, and a liar. But he was lovable. He had a warm heart, amazing energy, a sharp mind, talent as a gifted artist, and a progressive politics. I loved him.

They reported on prison conditions and other news that no corporate newspaper would touch.

Joe was the founder and publisher of Prisoners Digest International, the most important, by far, prisoners’ rights underground newspaper of the seventies — and possibly of all time. Although it was short-lived, it made its way into San Quentin, Joliet, Soledad, Leavenworth, and other prisons around the country and the world. There, inmate correspondents reported on prison conditions and other news that no corporate newspaper would touch or even think to be newsworthy.

Stop the Presses! I Want to Get Off! is Joe’s story of how he came to publish Prisoners’ Digest International, or Penal Digest International, as it was originally called.

It was my good fortune to work with Joe as his editor.

It Began with a woman

It began with a woman. I know that’s a cliché. It’s corny. It’s embarrassing. But there’s no other way to say it. I broke up with a woman, got depressed, fell into my “woe is me” state of mind, and did what I always did in the early seventies when I was depressed or restless: I hit the road. It was May 1972.

My first stop was Madison, Wisconsin, one of the Midwest countercultural hotbeds of the era; then Boulder, Colorado, home of my all-time oldest friend, who was going to school out there. I traveled by my usual mode of transportation, my thumb. And so on this particular afternoon I was hitching west on I-80 from Madison to Boulder and I got let off in Iowa City. Before I had time to recharge my thumb, a car pulled up alongside me. Two guys sat in the front seat. The guy sitting shotgun said, “Where ya headed?”

I said Boulder.

“Hungry?” he asked.

I was, although I didn’t pay much attention to hunger in those days. I fed off the exhilaration of being on the road, going whichever way the wind blew, waving the shopping bag that revealed my destination so seductively — while always giving direct eye contact — that drivers had no choice but to either stop and offer me a lift or, well, pass me anyhow, but if they passed me up they knew that I knew that they knew that I was standing there and so they felt guilty, and in the world of hitchhikers, that’s known as a consolidation prize.

And if all that didn’t satisfy my hunger, I always had a bag of raisins in my knapsack — they were inexpensive, they lasted forever, they never went bad, and you could squeeze them into any open bubble of space in your backpack.

The guy sitting shotgun opened the back door, I hopped in, and they drove me to 505 South Lucas, their office and home.

On the way to 505, as they called it, they explained to me that they were ex-cons and that they worked on a paper called Penal Digest International, or PDI. I had never heard of Penal Digest International because it wasn’t a member of Underground Press Syndicate, the first nationwide network of countercultural underground papers from the sixties and seventies, including Joint Issue, the paper I worked on in Lansing, Michigan.

I was intrigued by the idea of a paper published by ex-cons & whose reporters were all prisoners.

But I was intrigued by the idea of a paper that was published by ex-cons, and whose reporters were all prisoners covering their respective “beats” in Folsom, Leavenworth, Soledad, Attica, and other prisons all over the country. The two guys spoke excitedly about the paper but they became even more passionate as they described the birth of the newest member of their collective, a girl who had been born less than a month before in an in-home ceremony that featured music in the background and a hash pipe being passed around the room in the foreground.

I was greeted warmly by everyone at 505 and I shared a delicious vegetarian dinner. While I was waiting for the meal to begin, I noticed a light table in the back room. I figured that was the newspaper office so I went over to take a look. A partially laid-out page was on the table so I started to read it to get a preview of the upcoming issue. Wouldn’t you know it, I discovered a typographical error. Ever the compulsive anal retentive, I had no choice but to correct it.

There was a desk next to the light table, and a typewriter on the desk, and a piece of paper in the typewriter, so I typed the word correctly. I cut it out with a scissors, leaving as little white space around the word as possible. Then I picked up the correctly spelled word with a tweezers, lightly daubed the back of it with Glue Stick, and carefully positioned it over the incorrectly spelled word, using the light that shined through the page from the light table to line it up correctly with the other words on the line. That was it, but I felt a lot better.

I can’t remember if I spent the night at 505 or had them take me back to the highway right away. What I do remember is that the visit left a major impression on me. I sent a letter back to the folks at Joint Issue that they published.

Sixteen years later

Sixteen years later, when I was conceptualizing what would become the first edition of Voices from the Underground: Insider Histories of the Vietnam Era Underground Press, I knew I wanted PDI to be included. I was fortunate that the Special Collections library at Michigan State University had copies of PDI, and the general library upstairs had an impressive phone book collection that included Iowa City. I perused the staff boxes and compiled a list of complete names — not just first names, nicknames, or pseudonyms. I looked them up in the Iowa City phone book hoping to find a match. I did. So I called her and asked her if she had written for Penal Digest International in the early seventies.

When she said she had, I described my project, and said I was looking for an insider to write a comprehensive history of the paper. Then, to burnish my PDI credentials, I told her about hitching west on I-80 and the two ex-cons and the baby being born and the hash pipe celebration.

Unfortunately, she said, she was not the right person to write an authoritative history of the paper. I asked who I had to talk to. She said Joe Grant. I said, “Can I have his phone number?” She said no.

But, she said, “If you give me your phone number, I’ll tell him to call you.” So I mustered up all the enthusiasm I could muster up and said, “Great,” and I gave her my phone number. But as I hung up the phone, I said to myself, “Well, you can kiss that one goodbye” — because, honestly, how many people, when they say they’ll call you back, actually call you back.

‘You were the only person, ever, to work on the paper, voluntarily, without being asked.’

Two weeks later, Joe called me back! As it turns out, Joe had been out of town the day I visited the paper. But apparently I had made such a memorable impression on those who were there that they told him about me when he returned. “Ken,” he said, “a lot of people stopped by 505 in those days. They drank our booze, ate our food, smoked our dope, partied with us, and slept with us. But you were the only person, ever, to work on the paper, voluntarily, without being asked.”

He said many writers and scholars over the years had asked him to tell his story but he had always said no. To me, he said yes. All because I had corrected a typo. So there’s a lesson for you anal retentives out there: Put that on your résumé. There’s a job waiting for you.

Over the next year and a half we formed a precious bond and a close friendship that continued to the end as he dove into writing his story and I dove into editing his story. By the time we were finished, it was one of the two longest stories in the first edition. I knew then that it should have been its own book. With publication of my updated, expanded, revised four-volume Voices from the Underground Series, that vision was realized as Joe’s story became all of volume four.

Hell holes, spirit of rebellion, and the story of PDI

And what a great story Joe tells. Joe had a few years on most of the rest of us who contributed to the Voices from the Underground Series. We were coming of age during the Vietnam era. Joe’s story begins in 1953 when many of us were in pre-school and Joe was in pre-Revolutionary Cuba serving in the U.S. Navy and he met and befriended a group of revolutionaries. It takes us through his years as publisher of a rank-and-file newspaper, then into Leavenworth where he did time in the mid-sixties for counterfeiting.

“Back then,” Joe writes, the feds “used Leavenworth for the truly incorrigible.”

Leavenworth was where they sent the prisoners when they closed Alcatraz.

Stepping into that prison and becoming part of it reminded me of the opening paragraph of Tale of Two Cities. It was the best and the worst place to do time. The best place to be if you wanted to serve your prison sentence and not be bothered by anyone — prisoner or guard. The worst place to be if you were hoping to make parole. The best place for quiet in the cell blocks. The worst place for informers. The best place for food. The worst place for library books. The best place if you could learn by observing and be silent until spoken to. The worst place if you had a big mouth.

Prisons in those days were hell holes, but there was a spirit of rebellion & reformation in the air.

Prisons in those days were hell holes — but there was a spirit of rebellion and reformation in the air. A certain segment of society believed that the purpose of prison was to rehabilitate prisoners, not punish them, so that when they were released they could return to society as well-adjusted citizens. So there were efforts to provide vocational classes; modernize libraries; expand visiting hours; improve medical care and food quality; recognize religious freedom; not censor mail.

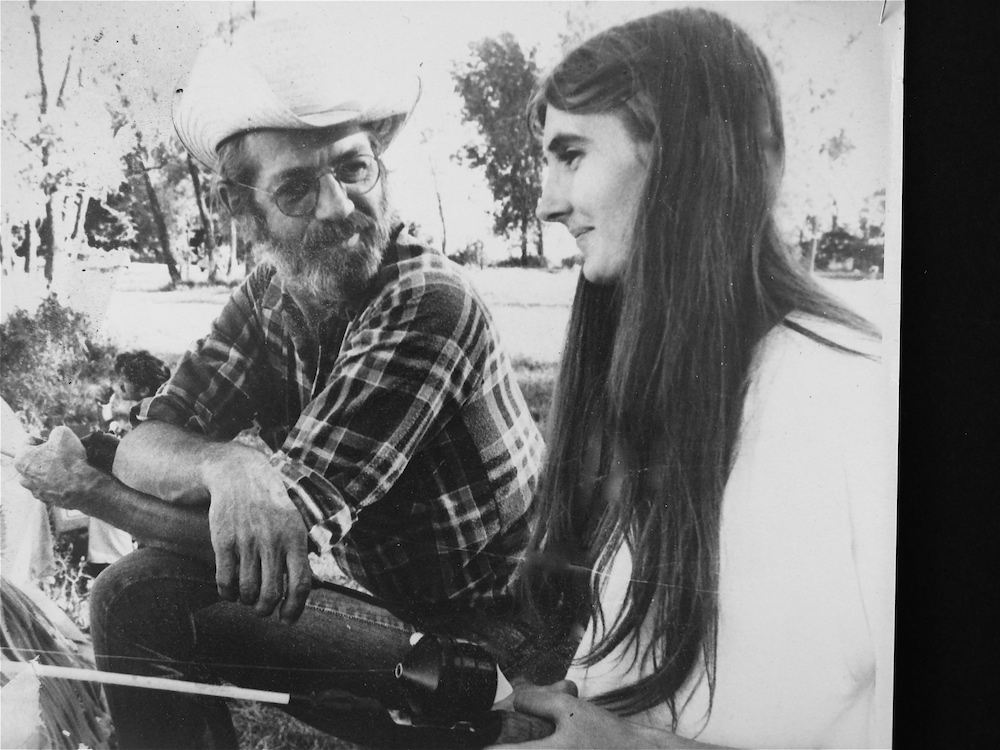

Joe and Shar Grant, final days of Prisoners’ Digest International, Bulger’s Hollow, Iowa, 1973. Image from PDI Archives / Azenphony Press.

Prisoners were catching the spirit of rebellion that was happening in the streets and becoming politically aware. They were overcoming differences that separated them from each other by race and religion and uniting around common causes, including with inmates from other prisons.

It was in this atmosphere that Joe’s idea began to take shape for Prisoners’ Digest International, a newspaper with two purposes: to provide prisoners with a voice that prison authorities could not silence and to establish lines of communication between prisoners and people in the free world.

The first PDI came out in spring 1971. During the paper’s brief history, Joe and the collective did more than just publish stories and poems from prisoners. As with the best of the era’s underground newspapers, they made news — and then reported on it. They stopped the extradition of an Arkansas escapee, ended an innocent Indian boy’s six years in prison, exposed behavior-modification experiments on prisoners through insider stories of surviving inmates, shared victories and defeats of jailhouse lawyers, stood up for prisoners outside Attica before the guards stormed the prison, and much more.

Joe was a natural story teller. In Stop the Presses!, he tells us

- about the first and only underground newspaper produced inside the walls of Leavenworth, naturally under Joe’s leadership;

- about the financial support he received from labor legend Jimmy Hoffa and from Playboy magazine;

- about the devoted collective of ex-cons, community folks, neighbor kids, and out-of-town visitors he attracted, including Jerry Samuels, who, under the name Napoleon XIV, wrote and sang “They’re Coming to Take Me Away, Ha Ha”; and

- the touching testimonial to his beloved mother that includes the never-before-told story about how singing legend Peggy Lee got her name.

Police harassment played a role in its ending,

and so did burnout.

The last PDI came out in spring of 1974. Not surprisingly, police harassment played a role in its ending, and so did burnout. Today, prison conditions are worse than they were then. Rehabilitation has been replaced by punishment and for-profit privatization as the guiding forces behind prison management. Fortunately prisons do still have some independent voices, including Prison Legal News. Joe and I were honored that publisher Paul Wright, himself an ex-con, wrote the afterword to Joe’s story.

And the most famous political prisoner in the world, former Black Panther Mumia Abu-Jamal, wrote the foreword. Personally connecting to anyone on death row requires persistence, creativity, serious networking ability, and good fortune. Whatever it was, I connected with him while he was on Pennsylvania’s death row, and he loved Joe’s story. Not long after that, he was released from death row and sent back to the general prison population for the first time in 29 years. Still, his treatment by the justice system is continued testament to Pennsylvania’s desire to silence him because he is a powerful voice of truth about prison conditions today.

Joe moves on to his next adventure

The last time I saw Joe was one week after I received copies of his book from our publisher’s distributor for my resale inventory. The timing was impeccable. It was August 2012. Emily and I were driving to Las Vegas with our daughter, Carrie, who was about to begin her three-year doctoral program in vocal performance at University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV).

It didn’t take much revising of the shortest route possible to bring us through Kansas, where Joe was living with his beloved wife Shar, ironically not far from Leavenworth Prison. I had visions of visiting Leavenworth with Joe and trying to deliver a copy of his book to the prison library. Naturally they would refuse our entry while the TV cameras rolled and the reporters took notes. Joe passed on the opportunity, not wanting to upset Shar, who was favoring a quieter life since their PDI adventure.

On April 19 of this year, I received a call from Joe’s daughter Charity, who had taken it upon herself to deliver the news of Joe’s passing to his network of friends. She told me that he had died on March 27 from natural causes: “He was part of the circle until the very end.” Ironically — or karmically, as is my preference — that day I was delivering a keynote talk on the underground press at a conference on radicalism in the electronic world at Michigan State, where my story had begun. Naturally, I mentioned my adventures with Prisoners’ Digest International. I choose to believe that Joe was at the talk with me and that, when he heard my PDI reference, he decided it was time to move on to his next adventure.

Joe was a legend. For all of his faults he was, as far as I knew him, a kind man, a generous man, a funny man, and — not to press the double meanings but never one to pass one up — a man of conviction. He is missed.

Find articles by and about Ken Wachsberger on The Rag Blog.

[Ken Wachsberger is a long-time writer, editor, political activist, and member of the National Writers Union. He is the editor of the four-volume Voices from the Underground Series and a driving force behind Independent Voices, Reveal Digital’s underground press digital project.]

Met Joe while in prison in Iowa & Wisc. Worked on prison newspaper. We corrasponded a lot. Now I’m out. Sorry about Joes passing. It was 1973 when I last heard from him. I was just 20 yrs. old, doing big time at Anamosa & Fort Madison, he helped me so much. Mike Brown