Called ‘kaleidoscopically gifted’ and ‘an American Balzac,’ John Updike died Tuesday, Jan. 27, of lung cancer at the age of 76. Many have tagged him the most important literary figure of our time.

By Thorne Dreyer / The Rag Blog / January 29, 2009

Includes commentary from a range of sources, some of John Updike’s own words, his essay on Ted Williams and a silly stoner video tribute.

An iconic American man of letters has left us. The prolific novelist, poet, critic and essayist John Updike has shuffled off this mortal coil to the tune of widespread fanfare.

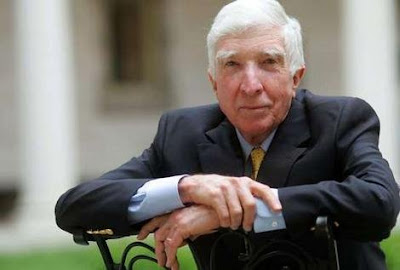

Called “kaleidoscopically gifted” by the New York Times and “an American Balzac” by the Guardian, John Updike died Tuesday, Jan. 27, of lung cancer at the age of 76. Many have tagged him the most important literary figure of our time.

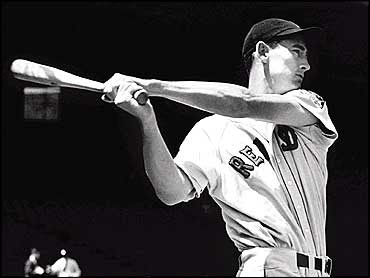

Best known for his “Rabbit” series of novels, and to sports buffs for his marvelous essay on slugger Ted Williams’ final at bat, Updike was also an acknowledged master of a sadly dying art form, the short story. His novel The Witches of Eastwick was made into a highly successful film starring Jack Nicholson and Susan Sarandon.

Though in general a critic’s darling, Updike also rubbed a few the wrong way, in matters both of content and style.

Christopher Lehmann-Haupt wrote in The New York Times:

The detail of his writing was so rich that it inspired two schools of thought on Mr. Updike’s fiction: those who responded to his descriptive prose as to a kind of poetry, a sensuous engagement with the world, and those who argued that it was more style than content.

And from Kelly McParland in the National Post:

As a writer, Updike was almost supernaturally talented. He was to prose what Wayne Gretzky was to hockey and what Tiger Woods is to golf. He had a painter’s eye for visual detail, a poet’s verbal range, a psychologist’s sense of emotional complexity, a dramatist’s feel for dialogue.

Updike drew criticism for his treatment of women in his fiction and some called his work misogynist.

Even John Updike’s appearance was an assemblage of contradiction: handsome in a beak-nosed kind of way.

This from Lehmann-Haupt:

He was a tall, handsome man with a prominent nose and a head of hair that Tom Wolfe once compared to “monkish thatch.” It eventually turned white, as did his bushy eyebrows, giving him a senatorial appearance. And though as a youth he suffered from both a stutter and psoriasis, he became a person of immense charm, unfailingly polite and gracious in public.

I have compiled a series of comments about – and by – John Updike, including an informative obit from the The Guardian and his legendary take on Ted Williams’ unforgettable farewell gift to his fans, a final at bat roundtripper.

Even threw in as an outro a video tribute to Updike by a couple of stoners with way too much time on their hands.

From John Updike’s contemporaries.

Novelist Philip Roth, quoted in the Times:

“John Updike is our time’s greatest man of letters, as brilliant a literary critic and essayist as he was a novelist and short story writer. He is and always will be no less a national treasure than his 19th-century precursor, Nathaniel Hawthorne.”

From novelist Joyce Carol Oates :

John Updike’s genius is best excited by the lyric possibilities of tragic events that, failing to justify themselves as tragedy, turn unaccountably into comedies.

Novelist Ian McEwan , quoted by BBC News:

He showed us, like 19th century writers, that it was possible to be a serious writer and a popular writer.

Many of his figures are men of the street – Rabbit’s quite a lowlife character, not an intellectual.

The great trick with Updike was to somehow give you the world through the fine mesh of a brilliant mind – ie Updike’s – but let the reader live all that through a rather uneducated man.

Novelist Martin Amis painted a telling portrait of John Updike in The Times Book Review from 1991:

Preparing his cup of Sanka over the singing kettle, he wears his usual expression: that of a man beset by an embarrassment of delicious drolleries. The telephone starts ringing. A science magazine wants something pithy on the philosophy of subatomic thermodynamics; a fashion magazine wants 10,000 words on his favorite color. No problem — but can they hang on? Mr. Updike has to go upstairs again and blurt out a novel.

A taste of Updike artistry. Just a tease.

John Updike, from an early short story, “A Sense of Shelter, quoted in the Times :

Snow fell against the high school all day, wet big-flake snow that did not accumulate well. Sharpening two pencils, William looked down on a parking lot that was a blackboard in reverse; car tires had cut smooth arcs of black into the white, and wherever a school bus had backed around, it had left an autocratic signature of two V’s.

An interesting piece on his passing.

An American Balzac by Nicolaus Mills in the Jan. 28, 2009, Guardian (UK):

“My subject is the American Protestant small town middle class,” John Updike once told an interviewer. He was being, as usual, modest. Updike’s subject was just about everything under the sun, and to that end, he turned out so much poetry, fiction and art criticism that it ended up filling 61 books.

Updike’s death from cancer at the age of 76 is hard to imagine. Even when he wrote about old age, he seemed young. His focus on crafting and recrafting his sentences until all that remained was elegance made one think of a prodigy bent on surprising his elders.

But Updike was no mere wordsmith. In his belief that people are a reflection of where they live and what they own, he was an American Balzac. Nobody worked harder than Updike to put a character in place, and in the future, social historians wanting to know how America made its transition from the Eisenhower 1950s to the Clinton 1990s will find Updike’s Rabbit novels required reading.

In 1960, readers first encountered Rabbit Angstrom in Rabbit Run, when after a hard day’s work he stopped to play a pickup game of basketball with neighbourhood kids. How pathetic Rabbit seemed at that first meeting. The kids didn’t want him spoiling their game, and he didn’t seem to notice. But then came Updike’s description of Rabbit shooting a basketball.

“The ball seems to ride up the right lapel of his coat and comes off his shoulder as his knees dip down. … It drops into the circle of the rim, whipping the net with a ladylike whisper. ‘Hey!’ he shouts in pride.” And we realise there is no taking Rabbit or Updike for granted. Rabbit may be a loser, but there is poetry in what he does. He is, we realise, as bent on living the dream of his youth as F Scott Fitzgerald’s Jay Gatsby ever was.

The Rabbit series would grow over the years, and Updike would fill his books with not only the families of eastern Pennsylvania, his birthplace, but the people of Ipswich, Massachusetts, and New York City, where he spent much of his adult life. Updike would even be at Fenway Park in Boston, when baseball great Ted Williams, in the last at bat of his career, hit a home run, and there, too, Updike’s prose made the moment magical. [See his essay on Williams below.]

“Like a feather caught in a vortex, Williams ran around the square of bases at the centre of our beseeching screaming. He ran as he always ran out home runs – hurriedly, unsmiling head down,” Updike wrote. “The papers said that the other players, and even the umpires on the field, begged him to come out and acknowledge us in some way, but he refused. Gods do not answer letters.”

Updike, a tall, thin man with an angular face, never saw himself having the physical grace of a Rabbit Angstrom or a Ted Williams. In a long autobiographical essay, “At war with my skin”, he once wrote with agonising candour about his psoriasis, and the difficulty it had caused him both as a child and an adult. But on paper Updike had no problems with being graceful. Long before his death, he brought to its peak a style of introspective writing that had its modern American roots in the short stories of John Cheever and JD Salinger, and its 19th century roots in the novels of Henry James.

Updike’s central character, not unlike himself, and his artful description of ordinary things.

Kelly McParland , about the development of his prototypical character:

In his 24 novels and nearly 200 short stories, John Updike, the great writer who died on Tuesday, created countless characters of all stripes and shapes ranging from a randy Toyota salesman to an African dictator to a coven of modern witches to a domestic terrorist. Yet there was one particular character-type who showed up recurringly in Updike’s fiction under various names and guises.

Sometimes he’s called Allen Dow, sometimes David Kern, sometime he’s nameless. Despite his different appellations, the lives of this character-type always follow roughly the same trajectory: He’s always a Pennsylvania boy, an only child born in the Depression, raised in a small town or farm by loving but embarrassingly dowdy parents and grandparents, a boy who dreams from a young age of flight from the constraints of his narrow upbringing.

As he matures, the boy gets to go to a good university, he marries young and fathers a large family but starts to feel stifled by domestic life. Again dreaming of escape, he starts having love affairs, but the pull of domestic life often thwarts these romances, as he’s torn between his children and his mistress. Even divorce and remarriage only complicate his family life, adding rather than subtracting to his web of emotional obligations. After his parents die, he takes another look at his Pennsylvania roots, visits the old haunts of his youth and realizes that the life he tried to run away from was the source of all his particularity and individuality.

The character-type I’ve been describing is, of course, a very close stand-in for Updike himself, since his life followed exactly the same arc. Much, although not all, of Updike’s art was autobiographical, so many of the intimate details of the writer’s life will be familiar to readers of his work.

From “John Updike celebrated the ordinary American” by Steven Winn in the San Francisco Chronicle:

A new Updike book – there were more than 50 – was always a deliciously anticipated pleasure. I felt it, coming of age as a reader, when each of the four “Rabbit” books arrived at the beginning of a decade from 1960-90. An Updike short story or poem in the New Yorker’s table of contents created the same heightened air of expectation. Even through his often personal late-career meditations on mortality’s dimming bulb, the Updike faithful never quite imagined it going out for good.

[….}

For half a century, those books spoke to one generation after another and are likely to speak to many more. In his glittering and multifaceted body of work, Updike deployed the finest prose of his generation with painterly precision, psychological acuity and heart-stopping emotional sweep, transforming the adulterous capers of suburban couples, a Pennsylvania car dealer’s private and family woes and the vacation travels of aging widows into a singular and incandescent art of the ordinary. He gave the sometimes discredited style of fictional realism both a lapidary sheen and an inner tensile strength.Updike saw and heard what anyone might – in the air-conditioned aisle of a supermarket in summer, an unfamiliar hotel room at night, the shadow-shrouded bedroom of someone else’s spouse, even in his own psoriasis – and often revealed something enduringly, even profoundly essential beneath the exquisitely rendered surface. The surpassing beauty of his prose merged with the preciousness of experience and existence itself.

The question of misogyny: the sexually active anti-hero and Updike’s treatment of women in his work.

From ‘Updike and Women, The Witches, The Widows, and the ambiguous bliss of misogyny,’ by AP obit by Emily Nussbaum in New York Magazine:

Updike has spent much of his long career perfecting a certain breed of anti-hero: the hyperobservant, resentful, libidinous fifties-era male who uses sex as a ballast against his diminishing status. It’s a theme he shares with Philip Roth and Norman Mailer (not to mention Woody Allen and Hugh Hefner), and yet Updike’s elegant prose set him apart. For many decades, he was the American bard of infidelity, a Puritan dirty-book writer whose beaky handsomeness was everywhere—the Wasp schnoz; the thatch of white hair; the curious, amused features. His worlds were stained with Christian guilt, his tone lyrical rather than pugilistic. On the cover of Time in 1968 for Couples, he hovered in that heavenly spot between literary genius and mass-market phenomenon, an avatar for the national struggle to reconcile stability and freedom.

The Witches of Eastwick marked Updike’s first attempt to delve deeply into female psychology. Like his peers, Updike had been taken to task for sexism. But unlike them, he “rose to the bait” over the years, he tells me with a certain satirical opacity. “People of my age are raised to be, sort of, chauvinists. To expect women to do the laundry and—it’s terrible! I’m making you cry, almost! But I’m eager to correct that as a writer, more than as a person. As a person, we always have chauvinistic assumptions. But a writer is supposed to be open to the world, and wise, and generous.”

And more on this subject from Historiann :

I was never a huge fan of his, since all of the male protagonists in his short stories were very clearly based on Updike: they all seemed to be men who were from lower middle-class families in industrial Pennsylvania who managed to go to Harvard and live lives with bigger houses, better cars, and prettier wives and paramours than their fathers had. That story got old, fast, as did the creepy obsession with comparing the girlfriend’s or second wife’s body with the first wife’s body, or sex with the girlfriend or second wife to sex with the first wife. Women in Updike’s short stories, and in many of his novels, function like the cars and houses of the protagonists–they were merely reflections of the protagonist’s status.

Updike’s attitude towards the world around him: social movements, politics and the Great Depression.

This is from an AP obit by Hillel Italie:

He captured, and sometimes embodied, a generation’s confusion over the civil rights and women’s movements, and opposition to the Vietnam War. Updike was called a misogynist, a racist and an apologist for the establishment. His characters, complained one younger author — David Foster Wallace — had no passion but for themselves.

“The very world around them, as beautifully as they see and describe it, seems to exist for them only insofar as it evokes impressions and associations and emotions inside the self,” Wallace wrote in 1997. “Though usually family men, they never really love anybody — and, though always heterosexual to the point of satyriasis, they especially don’t love women.”

On purely literary grounds, he was attacked by Norman Mailer as the kind of author appreciated by readers who knew nothing about writing.

John Updike, speaking on politics and the depression, from Updike: Unpublished Thoughts on the Great Depression and Barack Obama by Nick Catucci in New York Magazine:

But the economic terror was very real. My father was a minister’s son and a responsible man who was out of work and had no idea how to get work. And he never forgot that. Never stopped voting Democratic, too. My secret hope is that if it is a [new] depression, everyone will start voting Democratic again!”

[….]

Being the child of Depression Democrats, I’ve never had a great love for Republicans, although some of my best friends, etc., are Republicans. I’ve lived my adult life mostly under Republican administrations, mostly after LBJ — there was just Clinton and Carter. And this deification of Reagan, you mention Reagan, somehow the waves will part! I remember when people thought it was incredible that he’d be elected — as incredible as it is for Sarah Palin to become V.P., it was incredible for him to become president. He was charming, though, in a way. And he sort of convinced you — my mother once asked, how does he convince everyone that they’re rich?I don’t know if we’re on the eve of a depression. It sort of showed us America at its best. The movies that came out of the Depression, they’re wonderful in a way. The rich are rich! And nobody blames them for it. Houses in Long Island, and flighty daughters, and limousines — figures of gentle fun. It’s funny to watch them, because they don’t have the anger you’d think it would have called forth. But America is a place where everyone could become rich.

John Updike the essayist: on art and baseball.

Updike wrote about pop artist Andy Warhol in Rolling Stone:

In 2003, Updike wrote a meditation on the life and career of Andy Warhol for Rolling Stone that ran in Issue 922. Updike begins the piece, “In becoming an icon, it is useful to die young, and Andy Warhol managed this in the nick of time, at the age of fifty-eight, with the help of lifelong frailty and some negligent postoperative care at New York Hospital.”

Read John Updike’s essay on Andy Warhol in Rolling Stone here.

And two from sportswriters, on John Updike, baseball and the famous Ted Williams essay. First, from Joe Posnanski in KansasCity.com:

He used to say that when he wrote he was aiming for “a vague little spot a little to the east of Kansas.” He became famous for his breathtaking descriptions, which could make anything — toilets, mudholes, worn carpet — seem oddly beautiful. In one of his short stories, he found God in a pigeon feather. There’s no telling what he could have done with Super Bowl media day.

But Updike has a different meaning for me. Some 48 years ago — when he was a relatively unknown 28-year-old writer — he wrote one of my favorite sports stories. It was called “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu,” and it first appeared in The New Yorker. I read it for the first time when I was in college — a professor pointed it out. By the time I was out of college, I must have read it another hundred times, at least. And every year since, at least twice every year, I read it still.

The essay is about Ted Williams’ last game in the major leagues. And it is written from the seats on the third base side of Fenway Park. Updike did not have a press pass that day. He did not interview Ted Williams after the game; as far as I know, Updike never spoke with Ted Williams. He did not quote any of Williams’ teammates. He did not talk to any of the pitchers who faced Williams. He simply wrote what he saw and what he felt, both as a baseball fan and a Ted Williams fan.

Goodbye to a writing hero, John Updike.

And this from Grahame L. Jones , in the Los Angeles Times sports blog:

Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist John Updike, who died Tuesday, was a baseball fan pure and simple. Anyone doubting the depth of his feelings for the game need only refer to a New Yorker magazine piece he penned in 1960 on Red Sox legend Ted Williams.

It was a 5,880-word essay, each sentence perfectly crafted. Here are just a few of them about watching the home run that Williams hit in his final at-bat.

Williams was 42 at the time. Updike was 28.

The ball climbed on a diagonal line into the vast volume of air over center field. From my angle, behind third base, the ball seemed less an object in flight than the tip of a towering motionless construct, like the Eiffel Tower or the Tappan Zee Bridge. It was in the books while it was still in the sky. …

Like a feather caught in a vortex, Williams ran around the square of bases at the center of our beseeching screaming. He ran as he always ran out home runs—hurriedly, unsmiling, head down, as if our praise were a storm of rain to get out of. He didn’t tip his cap. Though we thumped, wept, and chanted, ‘We want Ted’ for minutes after he hid in the dugout, he did not come back.

One man could hit. The other could write.

Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu by John Updike, from the Oct. 22, 1960 issue of the New Yorker:

Fenway Park, in Boston, is a lyric little bandbox of a ballpark. Everything is painted green and seems in curiously sharp focus, like the inside of an old-fashioned peeping-type Easter egg. It was built in 1912 and rebuilt in 1934, and offers, as do most Boston artifacts, a compromise between Man’s Euclidean determinations and Nature’s beguiling irregularities. Its right field is one of the deepest in the American League, while its left field is the shortest; the high left-field wall, three hundred and fifteen feet from home plate along the foul line, virtually thrusts its surface at right-handed hitters. On the afternoon of Wednesday, September 28th, as I took a seat behind third base, a uniformed groundkeeper was treading the top of this wall, picking batting-practice home runs out of the screen, like a mushroom gatherer seen in Wordsworthian perspective on the verge of a cliff. The day was overcast, chill, and uninspirational. The Boston team was the worst in twenty-seven seasons. A jangling medley of incompetent youth and aging competence, the Red Sox were finishing in seventh place only because the Kansas City Athletics had locked them out of the cellar. They were scheduled to play the Baltimore Orioles, a much nimbler blend of May and December, who had been dumped from pennant contention a week before by the insatiable Yankees. I, and 10,453 others, had shown up primarily because this was the Red Sox’s last home game of the season, and therefore the last time in all eternity that their regular left fielder, known to the headlines as TED, KID, SPLINTER, THUMPER, TW, and, most cloyingly, MISTER WONDERFUL, would play in Boston. “WHAT WILL WE DO WITHOUT TED? HUB FANS ASK” ran the headline on a newspaper being read by a bulb-nosed cigar smoker a few rows away. Williams’ retirement had been announced, doubted (he had been threatening retirement for years), confirmed by Tom Yawkey, the Red Sex owner, and at last widely accepted as the sad but probable truth. He was forty-two and had redeemed his abysmal season of 1959 with a—considering his advanced age—fine one. He had been giving away his gloves and bats and had grudgingly consented to a sentimental ceremony today. This was not necessarily his last game; the Red Sox were scheduled to travel to New York and wind up the season with three games there.

Read all of John Updike’s essay on Ted Williams here.

And now for something completely different: in case you’ve forgotten about whom we’re talking, here’s a hip hop reminder from Gabe at Videogum . Gabe calls the following video “an incredible homage to the man’s legacy.”

Gabe’s final words:

Perfect. These guys really nailed it…

R.I.P. John Updike. You’re up in heaven now, sleeping around on the angels.

Wouldn’t even try to follow that. Run, Rabbit, run

John Updike’s passing is sad, but he left a ton of awesome work. “Immortality is nontransferrable” he said appropriately.