Danny was involved in a precedent-setting landmark case before the U.S. Supreme Court.

With tributes from friends John R. Herrera and Roger Baker

In September 2015, our mutual friend Roger Baker brought Danny Schacht to the KOOP-FM studio in Austin where we were preparing to broadcast a live Rag Radio interview with Austin-based progressive pundit and troublemaker Jim Hightower. Danny sat in the studio with us and then took a terrific photo of Jim and me afterwards. It’s on my wall. It was the first time in many years I had been with my old compatriot and family friend from the ‘60s.

Then I saw Danny again during launch events for Exploring Space City!: Houston’s Historic Underground Newspaper, a book that the New Journalism Project released in 2021. It was a delight to see him; he was funny and smart and always had that twinkle in his eye! But that would be the last time I would see him. Longtime Houston activist Daniel Jay Schacht, known to his many friends in the movement and local community as Danny, passed away on December 22, 2022, at the age of 77.

Danny was involved in a precedent-setting landmark case before the U.S. Supreme Court after being arrested in September 1969, when he wore a military uniform as part of a street theater action at the Houston draft board. He was convicted for impersonating a military officer, but the Supreme Court reversed the case. We’ll discuss that case – and its significance — in more depth below.

Danny Schacht had been my close friend since the mid-‘60s. He worked in electronics with his father (who was an electrician by trade), and was an amateur inventor. Danny was also a leftist and anti-war activist. He took photographs for The Rag, a ‘60s-‘70s Austin-based underground newspaper that was also briefly published in Houston. Danny and friend Raymond Ellington later co-wrote a column on Texas labor history for Houston’s Space City! called “From the Other Side of the Bayou.” I was an editor of both papers. About the Space City! column, Sherwood Bishop wrote in the book Exploring Space City! that Danny and Raymond “described Texas labor history that wasn’t taught in the schools or labor halls.” “They reached back into buried Texas history,” he said.

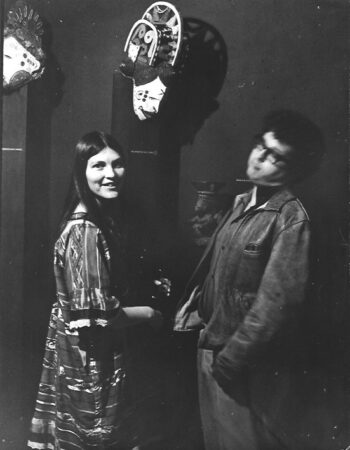

Danny’s parents, Ezra and Mona Schacht, were European Jews who came to Houston from New York. Themselves leftists with family roots in Left politics, they were well-known for being supportive of Danny’s friends and other young activists in Houston, often providing a home away from home. The Schachts were friends of my parents, artist Margaret Webb Dreyer and journalist Martin Dreyer, who owned an art gallery and who played a similar role nurturing young activists, artists, and intellectuals. I still have a photo, taken at Dreyer Galleries in the late ‘60s, of Danny and Scout Stormcloud Schacht, to whom he was briefly married. Scout, who wrote about music for Space City!, was one of many young people who assisted my mother at the gallery. Scout Stormcloud Hook is now an accomplished painter and photographer.

Danny was a leader of the Houston chapter of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and worked with other movement groups including the W.E.B. DuBois Clubs and anti-war organizations. In a story titled “Houston SDS under attack,” the May 1968 edition of The Movement newspaper reported that “three shotgun blasts ripped through two rooms of the family home of Daniel J. Schacht, an SDS war protestor, in the latest of a series of threats and violence attributed to the local KKK aimed at Houston’s anti-war movement.” Luckily, no one was home.

Danny calls cops ‘a disgrace to their uniforms.’

In July 1967, two years before the Supreme Court case in 1969, I wrote a cover article in The Rag called “Houston: While Cops Disappear, Marines Attack Peaceniks.” It was about a large “support our boys” parade that drew hundreds to Houston’s Hermann Park. The rally was organized by an ad hoc right wing group called Citizens United to Support our Armed Forces.

A group of about 40 local anti-war demonstrators and Black activists from SNCC (the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) attempted to join the march, carrying a banner saying “Support Our Boys; Bring Them Home Now.” As I wrote in the article, “a group of over 100 marine reserves, dressed in fatigues, moved in ahead of us. They allowed the rest of the parade to move out, while they remained immobile, blocking us….

“Suddenly the Marines stopped and the cops directed the rest of the parade around them and on down Main Street. We were trapped. We started to go around the Marines… but they moved in, yelling and pushing… The whole group sprang like a taut slingshot, suddenly released…

“As soon as I reached the other side, a Marine came up from behind me and his fist slammed against the side of my neck. I fell to the pavement, striking my collarbone on the concrete. I was very dizzy and could hardly stand up. At some point I was also kicked in the side of the face…

“The fighting had about subsided when two cops appeared, dragging Danny Schacht to a cop car.… [Danny] was taking pictures for The Rag and appeared on the scene while the fighting was going on….

“Danny told the cops that ‘they were a disgrace to their uniforms and had been negligent in their duties… Why didn’t you help the people being beaten?’ he asked. “He was told to move on and he refused. So they grabbed him and dragged him to the cop car…” And took him off to jail.

Landmark Supreme Court case

Danny was involved in a significant landmark case before the U.S. Supreme Court after being arrested in December 1967, when he wore a military uniform as part of a street theater action at the local draft board. He was charged with impersonating a military officer.

The following account was adapted from Wikipedia by The Rag Blog’s Mariann Wizard. We are running this in-depth report because we think it is pertinent in its entirety.

On December 4, 1967, Daniel Jay Schacht, Jarrett Vandon Smith, Jr., and a third person participated in a national protest of the Vietnam War by performing a skit in Houston, Texas, portraying the murder of Vietnamese civilians by the U.S. Military. Schacht was dressed in a military uniform and cap. Smith was wearing “military colored” coveralls. The third person was wearing “typical” Viet Cong apparel.

Schacht and Smith carried water pistols with which they would shoot the “Viet Cong.” The water guns contained a red liquid that, when it struck the victim, looked like blood. When the “enemy” fell down, the other two would walk up and exclaim, “My God, this is a pregnant woman!” Without noticeable variation this skit was reenacted several times during the demonstration.

That night, armed FBI agents cornered Danny’s car and arrested him as he left his father’s electronics plant. One of them bragged that he had spent the entire day trying to identify a federal crime they could use to arrest him. Schacht and Smith were charged with violating 18 U.S.C.A. 702, impersonating members of the armed forces. However, the statute had an exception: an actor in a theatrical or motion picture production could wear a military uniform if the portrayal did not discredit the military. Put another way, it was okay to wear an Army uniform so long as you spoke lovingly of the Army.

At Danny’s trial, the Assistant U.S. Attorney pointed to him and yelled, “If Schacht comes to my house and expresses himself like this he won’t be able to walk into this courtroom to stand trial!” Then, as he moved menacingly toward both defendants, “The only thing I gather from these defendants is that they are displeased with the government and the war. But I have a simple answer to that. There is a plane and boat [sic] leaving two or three times a day for other parts of the world. I can probably name you gentlemen the place to go. If you don’t like it, get out.”

Smith and Schacht were convicted by a jury. U.S. District Judge James Noel sentenced Vandon Smith to probation. Then, while punching holes in a piece of paper with a pencil, he glared at Danny and said, “Schacht’s express purpose was to discredit the United States… to leave the impression to all watching that the soldiers of the country were attacking innocent people who were being killed by shooting… In my opinion, the defendant acted heedlessly and he has not expressed the slightest bit of remorse.”

Noel sentenced Danny to the maximum possible term under the statute: $250 and six months in a federal penitentiary. Sixteen days later, on March 15, 1968, U.S. Army Lieutenant William Calley led his troops into the tiny village of Mai Lai, Vietnam, where they slaughtered at least 347 unarmed men, women, and children.

The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed Danny’s and Vandon’s convictions. Smith did not seek Supreme Court review. Schacht thought his ACLU lawyers had filed a petition for writ of certiorari seeking judicial review, but they had not, and soon after the time for filing the petition expired, a warrant was issued for his arrest. Danny surrendered to U.S. Marshals just after Labor Day, 1969, and was sent to the federal lockup in Seagoville, Texas. A few days earlier, Schacht’s father Ezra, a lifelong radical activist once arrested for displaying a sign in his yard supporting a Black candidate for Houston’s City Council, had retained attorney David Berg to help his son.

Berg and his partner, Stuart Nelkin, filed a petition for writ 101 days late. The Supreme Court makes its own rules, They relaxed the rule setting deadlines for filing an appeal. On December 15, 1969, the Court granted certiorari with three judges dissenting. Judge Noel, aware that the decision signaled a likely reversal, released Schacht on bail pending the outcome.

On March 31, 1970, Berg, then 28 years old, argued the case before the Supreme Court against Solicitor General and former Dean of Harvard Law School Erwin Griswold. On May 25, 1970, the Court unanimously reversed Schacht’s conviction, striking that portion of the statute prohibiting portrayals of the military in a manner that tends to discredit the armed forces as a violation of free speech. Vandon Smith’s conviction was vacated in later proceedings in the district court.

The Schacht decision legitimized what was called “guerrilla theater” and set a precedent allowing late-filed cases to proceed to SCOTUS if warranted by the circumstances.”

A remembrance of Danny Schacht by his friend John Herrera:

When I heard of Danny’s passing, I was sitting in my car, just having gotten out of physical therapy. A longtime friend texted me the news. For about 10 minutes, I just sat there in shock and disbelief. Even though I had not seen or talked to Danny in a while, it was still hard to absorb the news.

I met Danny in 1965-‘66, through his younger brother Larry, when I was a senior in high school and just starting to get active in the Vietnam anti-war movement and the growing student movement. Danny, a couple of years older than me, was already hooked into SDS and the W.E.B. DuBois clubs. He gave me a copy of Insurgent magazine, published by the DuBois clubs. I guess in some ways I was sort of star-struck. I had finally met someone who could answer a lot of my questions, and maybe even offer some political direction.

It was about then that Danny was arrested at an anti-war demonstration in front of the local draft board. He was wearing a military officer’s jacket for his role in a guerrilla theater skit. He eventually won his case before the Supreme Court. At the time, I didn’t realize there were so many layers to this guy.

Little did I realize how much Danny and his whole family would change my life. At the time, my family was not supportive or understanding of who I was or of my growing radical left ideas. The Schachts were a huge influence on a generation of young Houston radicals. Their home was always open to young people in search of new directions.

I vividly remember sitting around their dining room table for hours. Discussions with Ezra, Danny’s dad, and Mona, his mom, veteran activists themselves, were moments I looked forward to, sustaining my growth on the Left. Ezra and Mona each had a mountain of stories of their activism in their younger days in New York City. I recently told a friend, you weren’t just friends with one of the Schachts, you got to know the whole family.

Although Danny did not maintain his youthful level of activism, he never stopped caring or being a friend. As we got older we still saw each other and continued to have long, interesting conversations, especially about politics and current events.

I appreciate the time I spent with Danny and consider myself lucky to have known him. I was honored that he felt he could confide in me as his various family issues arose.

I’ll always remember those times at the Schacht residence, and the happiness they brought to a youngster searching for answers. Rest in peace, my friend.

And finally, some words from Roger Baker, who remained close friends with Danny up until his death.

I met Danny as one of a group of young Houston political activists. Danny came from a European Jewish heritage but neither he nor his parents were observant. They were, however, decidedly on the Left. His father Ezra, whom I got to know well and worked for briefly, had been close to or possibly a member of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, a group of U.S. citizens who fought against the fascists in the Spanish Civil War.

The facts were obscure due to anti-Communist laws that made the Brigade, and many other organizations, illegal even in retrospect. “Are you now or have you ever been?…” was a defining question in almost every area of life. Danny’s mother, Mona, was a left-wing political organizer whose youthful affiliations remained unspecified in the 1960s and 1970s because of these misbegotten laws.

In 1967, before we met, Danny had been arrested and imprisoned for protesting the Vietnam War while wearing parts of a military uniform. He eventually won a Supreme Court case that ruled wearing military dress while protesting was a legitimate form of free speech. I think he may have decided then that being a political activist was not a great career choice.

Although Danny was not as political as I was, he was part of a small circle of interesting Houston iconoclasts like the late Lynn Clarkson and the late Frank Lurie, rumored to have been the basis for the character Freewheelin’ Franklin of Gilbert Shelton’s Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers comix.

My common interest with Danny was mostly in technology since I was a committed home scientist and inventor as he was, too. His dad had an electronics company, and Danny’s home was a workshop full of interesting electronics and books. We often conferred and worked on solving technical problems together. Both Ezra and Danny acted as patent agents to help others get patents. Danny sold miniature radiation detectors that he designed himself at one point.

Well-read, full of opinions, and always interesting to talk with, Danny Schacht was my friend for over 50 years.

For many of us who came of age in the ‘60s and ‘70s, our friendships would last the rest of our lives, even if we rarely saw each other in the later years – as was the case with me and Danny. He was a special person and I shall miss him dearly.

[Thorne Dreyer, is an Austin-based writer, editor, broadcaster, and activist. He was a founding editor of the original Rag in 1966 Austin and Space City! in Houston. He was a programmer at and general manager of KPFT-FM, Houston’s Pacifica radio station and he now edits The Rag Blog, hosts Rag Radio at KOOP 91.7-FM in Austin, and is a director of the New Journalism Project. His book Making Waves: The Rag Radio Interviews, was published by the Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas and can be found at this link. Contact Dreyer at editor@theragblog.com.]

Thanks to Thorne and others for this detailed remembrance of a valued friend. I understand the sense of loss, and send sincere sympathy wishes. I’m glad I got to know something about Daniel by reading this. Best wishes to all. Here is an additional thought: as rock music fans are dealing with losses (Jeff Beck and David Crosby most recently), we on the left are also dealing with losses as time relentlessly marches on.

Thank you, Thorne, for all that you have done and continue to do, including keeping these important histories alive — and the people who lived them.

I lived across the street from Danny for 17 years. We had long talks at the grocery store when I’d see him. He repaired my old tube system power module and we had

many common friends. He was home often and I was welcome but did not stop in and regret that. I saw a pile of debris outside the house and wondered what happened…and now he’s gone. Thorne ..thank you for getting this out.

I too was a friend of Danny’s, and we were both members of the Young Peoples Socialist League for a while … improbably, this group had 15 members in Houston in the early 60s. We had our political differences, which I won’t go into because they’re irrelevant now. As others have noted, Danny had a wry sense of humor. I recall a comment he made in the late 1990’s, as Russia was suffering from its abrupt transition to capitalism, with shortened life spans, falling birth rates and gangsters taking over the economy: “Those darned Russians … first they discredit socialism, now they’re discrediting capitalism.” RIP Danny.