Jonah reviews Chellis Glendinning’s memoir about her friends, lovers, and comrades.

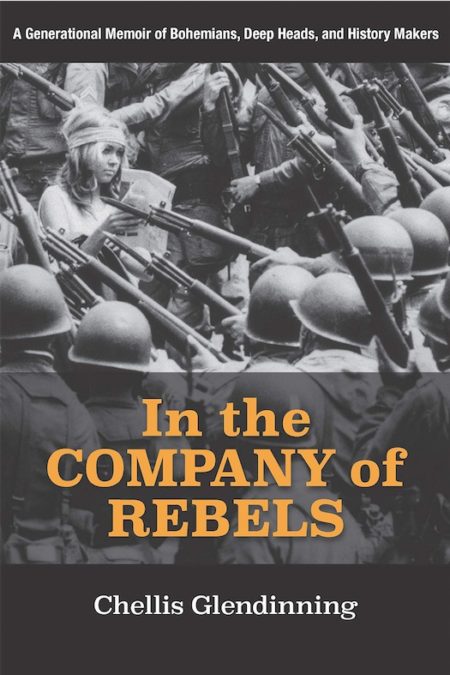

At the very start of her new heartfelt book — In the Company of Rebels: A Generational Memoir of Bohemians, Deep Heads, and History Makers ($24.95, New Village Press) — about her friends, lovers, and comrades, Chellis Glendinning asks why one should bother to learn about “other generations’ attempts to bring justice, peace and beauty into this tattered world.”

Her answer a few paragraphs later is expressed in two words, “History rocks,” which might satisfy the needs of rock ‘n’ rollers and their ilk but probably won’t appeal to historians and scholars.

Imbued with the idea that her contemporaries — the rebels of the last 50 or so years — “have been sturdy, creative, courageous catalysts” Glendinning recounts some of the key movements of contemporary history and offers compact and compelling biographies of 46 individuals, some of them household names in lefty homes and others hardly known at all, or mostly forgotten.

Enthusiasm informs every page and a sense of solidarity infuses all the chapters.

Each individual comes with a tagline, a phrase, or a slogan. Susan Griffin is “The Ardent Intellectual.” John Zerzan is “The Green Anarchist.” Peter Barnes is “The Pretend Banker.” Tom Hayden is “The Political Animal.” Pat Cody is “In the Center of It All.”

Glendinning connects people to places — like Berkeley and Vermont — the personal to the political and the lives of public figures such as Daniel Ellsberg to causes including feminism, anarchism, environmentalism, and pacifism.

In The Company of Rebels is a kind of Who Was Who in radical circles, from the 1960s to the present day. Most of the rebels in the book are still alive. Many are still kicking.

Enthusiasm informs every page and a sense of solidarity infuses all the chapters. In the preface, Glendinning writes that “the forces-that-be have forged a renewed form of colonialism” and that “the most recent subjects are all of us.”

No hierarchy of the exploited and the oppressed for the author.

No hierarchy of the exploited and the oppressed for the author, but rather a gathering of “fine folk” who have all tried in their own ways to make the world less noxious and more habitable for humans, animals, and all living things.

There isn’t a lot about the twenty-first century and much of what there is doesn’t go very deep. The “assault” on the Twin Towers and the Pentagon in 2001 is an example, the author writes, of “what the CIA refers to as ‘blowback.’” Glendinning doesn’t employ those much abused words, “terrorism” and “terrorists.”

She writes about the “debilitating malaise” that followed the initial euphoria that accompanied Obama’s election to the White House,” and she describes the “alarming shadow of U.S. racist, right-wing populist movements and a loudmouth, emotionally unbalanced president.”

She doesn’t have to say his name. We’ve all heard it ad infinitum and ad nauseam. We’ve also heard words like “fascism” used repeatedly and don’t need to hear them again and again.

Glendinning chooses her words carefully. For her, the problem isn’t capitalism, imperialism, or the patriarchy, as it is for some feminists, but rather civilization itself — more specifically “Western civilization.”

After all, she’s the author of My Name is Chellis and I’m in Recovery from Western Civilization.

Some of Glendinning’s intriguing ideas are presented without much discussion.

Some of Glendinning’s intriguing ideas are presented without much discussion or elaboration, as for example the idea that in the colonial world trauma is contained in the “conscious mind” while trauma in the belly of the beast is “holed up in reticent, unconscious fragments.”

Perhaps so! But what about colonized subjects who identify with their oppressors, and members of the privileged classes who join guerilla movements? And how to understand the global shift to dictatorship and authoritarian rule in Brazil, Turkey, Russia, Egypt, and Hungary?

Glendinning doesn’t try to explain how we as a species have arrived at the present situation with dissenters and rebels in prisons all around the world. She tends to be blindsided by history in part because she’s so enthralled with a sense of human goodness.

She might have been less shocked than she was by the digital revolution, for example, had she listened to writers like Huxley, Orwell and Doris Lessing who warned of dystopia.

But probably if you listen to gloom and doom thinkers you wouldn’t go into the streets to do battle against the empire for half a century.

At least Glendinning doesn’t fall for the gospel of hope, nor does she forget that what counts, isn’t hope, but fight.

If you want to find the Yippies in his book you will look in vain. Same for Black Panthers, Young Lords, trade unionists, and working class organizers who slogged it out with bosses and cops in factories and on picket lines. And there aren’t enough folks from Kansas, Nebraska, and Texas.

‘In The Company of Rebels’ is an honorable act of remembering and sharing.

In The Company of Rebels is for fighters. It’s for people who want to look at the past with a sense of pride and achievement.

A hundred or so pages from the end, Glendinning offers a quotation from Jeanette Armstrong, who belongs to the Okanagan in British Columbia, and who says, “Our challenge is to remember who we are — despite all the brokenness, despite all the paradoxes, despite all the ways we cannot remember or haven’t been told.”

In The Company of Rebels is an honorable act of remembering and sharing. Sometimes it’s funny. At other times it exudes a sense of wonder and magic.

It will introduce readers to underappreciated souls such as Shepherd Bliss and Suzan Harjo and it will encourage movement veterans to salvage their own memories and stitch together narratives that make sense of the past and enable us to continue on a journey that we have undertaken together and can’t abandon now.

In her next book, Glendinning might describe how and why she moved to Chuquisaca, Bolivia, and whether or not we should join her there.

[Jonah Raskin, is the author of For The Hell of It: The Life and Times of Abbie Hoffman, the editor of The Radical Jack London: Writings on War and Revolution and a longtime contributor to The Rag Blog.]

- Read articles by Jonah Raskin on The Rag Blog and listen to Thorne Dreyer’s Rag Radio interviews with Jonah.