The playful gist was that the Internationale would be the new national anthem played at baseball games.

Rag Blog author Steve Rossignol recently retired as an IBEW electric worker. He turned his attention to the rich vein of union and socialist history in Texas, Oklahoma and Louisiana to ensure that this earlier period of insurgency would be remembered. A century ago, both the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and the Socialist Party were active in Texas and adjoining states.

William Covington Hall, a Wobbly labor organizer who led the East Texas Lumber Workers in their strike at Grabow, Louisiana, in 1912, was a writer, poet, labor organizer, and socialist. Steve’s research came to our attention when Steve asked for help to place a marker on Covington Hall’s unmarked grave. We asked him to write something about the Wobblies and Socialists in Texas. He did and is still working on the Covington Hall article.

During the Seventies and Eighties in Austin and the Hill Country, our socialist meetings and encampments would sometimes be punctuated by the singing of those old socialist songs, especially the Internationale. Invariably at the conclusion of that venerable hymn of the proletariat, Travis would shout out, “Play ball!” — the playful gist of the comment implying that the Internationale would be the new national anthem played at baseball games.

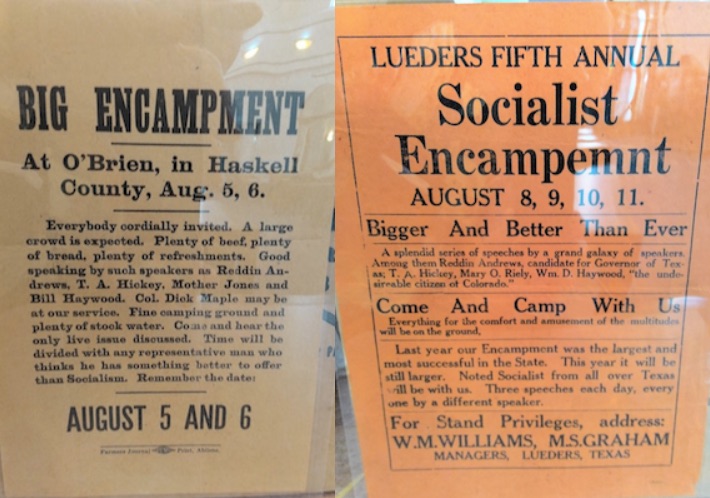

Quite possibly the closest time that ever happened in history was in Desdemona, Texas, in the Nineteen-Teens. The fate of Desdemona would change overnight on September 2, 1918.; in 1912 Socialist candidate Eugene Debs almost received more votes for President in the state than the Republican Party candidate. Dozens of Socialist candidates were elected to local offices statewide. Socialist encampments were held throughout the state — up to 25 or 30 a year — especially in the “Red Belt” counties of the Texas Big Country — Eastland, Comanche, Stonewall, Erath, Stephens, Haskell, and others.[i]

In Eastland County, Ellison Springs became one of the major socialist encampment draws in the area. Settled by James Madison Ellison and his family in the 1850s, the religious camp meetings there of an earlier era evolved into the Populist camp meetings of the 1890s and thence into a yearly socialist event in the Nineteen-Teens featuring major socialist speakers, carnival-like events, and baseball games.

Soon the informal socialist baseball games grew into an established baseball team.

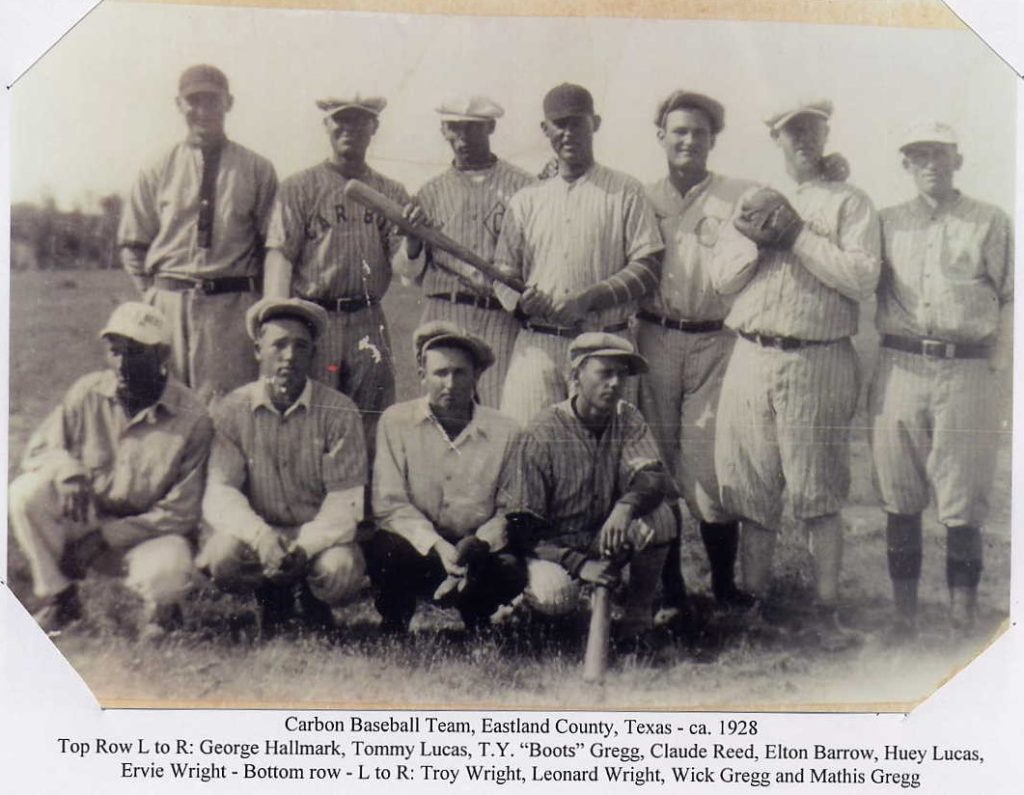

James “Uncle Jimmie” Ellison hosted the socialist event; Socialist Party of Texas organizer Thomas Aloysius Hickey was always a principal speaker. Soon the informal socialist baseball games of the Ellison Spring encampment had grown into an established baseball team, playing from the nearest community of Desdemona, six miles east-northeast of Ellison Springs. The Desdemona Socialists[ii] were soon playing other informal sand-lot teams from Gorman, De Leon, Comanche, and Stephenville.

The Desdemona Socialists staked out a home-made baseball diamond on a vacant field owned by Desdemona patriarch Dr. Samuel E. Snodgrass. Snodgrass, who moved to Eastland County in 1885, was a longtime resident of Old Hogtown, the name of Desdemona before it became Desdemona, and in addition to being a medical doctor was quite the local entrepreneur, establishing a dry goods store, selling real estate, selling chickens, banking, operating a cotton mill, and working in the cattle business. Snodgrass was also a hard-core Democrat.

The Desdemona Socialists maintained a very healthy batting average.

The Desdemona Socialists maintained a very healthy batting average; Tom Hickey reported on their glowing success: “our local baseball team [which] has cleaned up its rivals wherever it has played.” [iii] (Tom Hickey goes on to report in this article the appearance of a “peculiar visitor” who reportedly was an undercover United States Marshal[iv]; the implications of this encounter would become all too evident in the years to come.)

One of the rivals cleaned up by the socialist baseball team was their local adversaries, the Desdemona Democrats.

The Socialist team was a composite group of the Desdemona citizenry, a town reported to be almost exclusively socialist[v], made up of socialists and the sons of socialists. L. L. Steele, the one-armed school-teacher, was on the team, as was fellow school teacher John James W. Munday and local farmer William Richard Carruth played ball, along with Oliver Payne and John Hawkins. Uncle Jimmie Ellison is listed as having played on the team; in his seventies at the time it would have been quite a feat. [vii]

Dr. Snodgrass, the hard-core Democrat that he was, apparently was a little disturbed by the fact that his favored political baseball team was continuously being trounced by the upstart Reds. The baseball lot in Desdemona apparently sat adjacent to the Snodgrass homestead; Snodgrass’s daughter Inez would later report how she would have trouble viewing the Saturday games with “all those men in the way.”[viii]

Snodgrass decided that he had had enough of the Desdemona Socialists playing on his land. He told the team that they could no longer play baseball on his property.

Undaunted, the local socialists offered to buy the land where the baseball field was located.

Undaunted, the local socialists offered to buy the land where the baseball field was located. Equally adamant, and being the entrepreneurial businessman that he was, Snodgrass demanded the then exorbitant price of $50 for an acre-and-a-half of land. The socialists of Desdemona began putting their principles of collective ownership into action. They undertook to raise the money by selling individual $1 subscriptions to the property and soon had the funds needed to purchase the Snodgrass sandlot.

A high picket fence was erected between the baseball field and the Snodgrass home. Inez Heeter would begin watching the baseball games from the roof of the Snodgrass house; she would also report that the new owners didn’t like the Snodgrasses and that her father “should have taken the land back.”[ix]

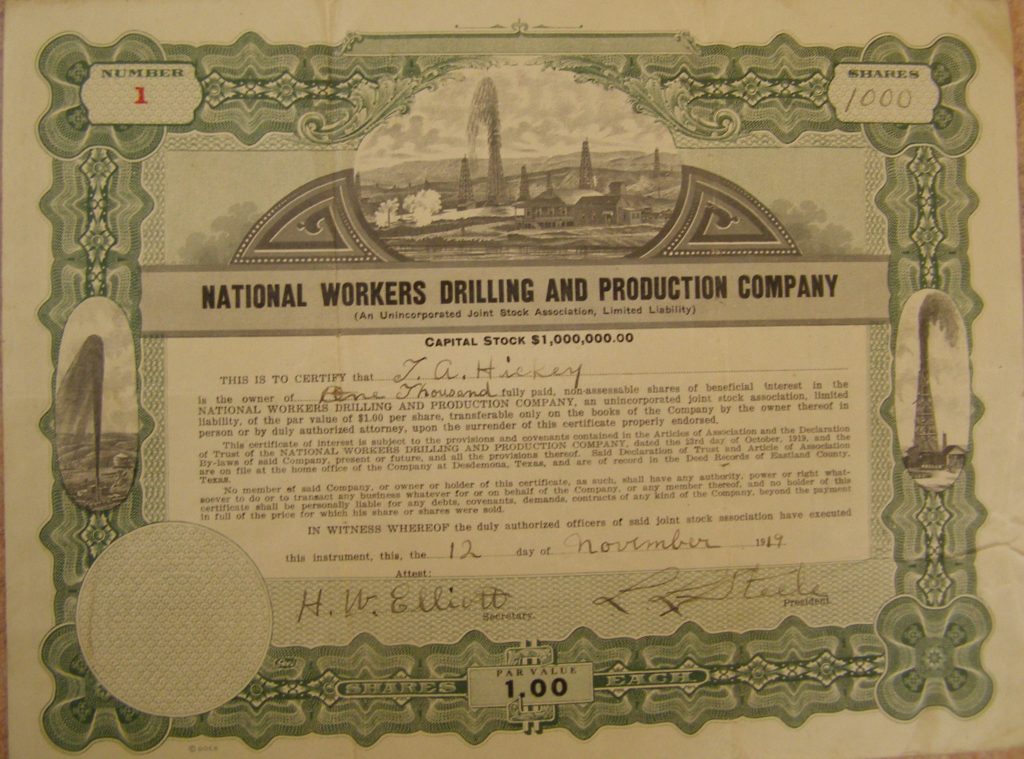

The cooperative buying of the baseball field was one of several attempts at collective ownership the socialists in Texas would undertake in the Nineteen-Teens. Among other examples, socialists in Paris, Texas, would build a collective slaughterhouse; Tom Hickey would sell socialist shares to finance The Rebel[x], and Desdemona barber John Walter “Shorty” Carruth (who may have been distantly related to Desdemona socialist William Richard Carruth) would solicit shares from the other socialist citizens of Desdemona for his new Hog Creek Oil Company.

In the midst of the enthusiastic baseball games, dark clouds approached.

But in the midst of the enthusiastic Desdemona baseball games, dark clouds were approaching. War fever was growing from the World War I conflict in Europe. Texas socialists were adamantly anti-war and did not hesitate to advocate against American entry into the conflict. The pages of The Rebel continued to rail against the war effort, and the Farmers’ and Laborers’ Protective Association, the cooperative association loosely affiliated with the Socialist Party and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), began speaking out against a probable military conscription.

On June 12, 1917, a grand jury in Dallas indicted 55 members of the FLPA and charged them with seditious conspiracy under the provisions of the Espionage Act, which made it a crime to speak out against the military draft. Among the allegations were that the members of the FLPA conspired to use force to oppose military conscription; that some had threatened to kill President Woodrow Wilson; and that they had conspired to destroy railroad tracks, bridges, and communication lines.[xi]

Other arrests occurred throughout the state.

Other arrests occurred throughout the state.[xii]-Ernest R. Fulcher, a FLPA member from the borders of Palo Pinto and Hood counties, while being sought by a posse from those counties on a “wife-beating charge,” was gunned down with 23 bullet wounds on June 4, 1917, after a stand-off with a shotgun that “missed-fire.” The large size of the posse was supposedly predetermined by Fulcher’s “threats” against conscription.[xiii]

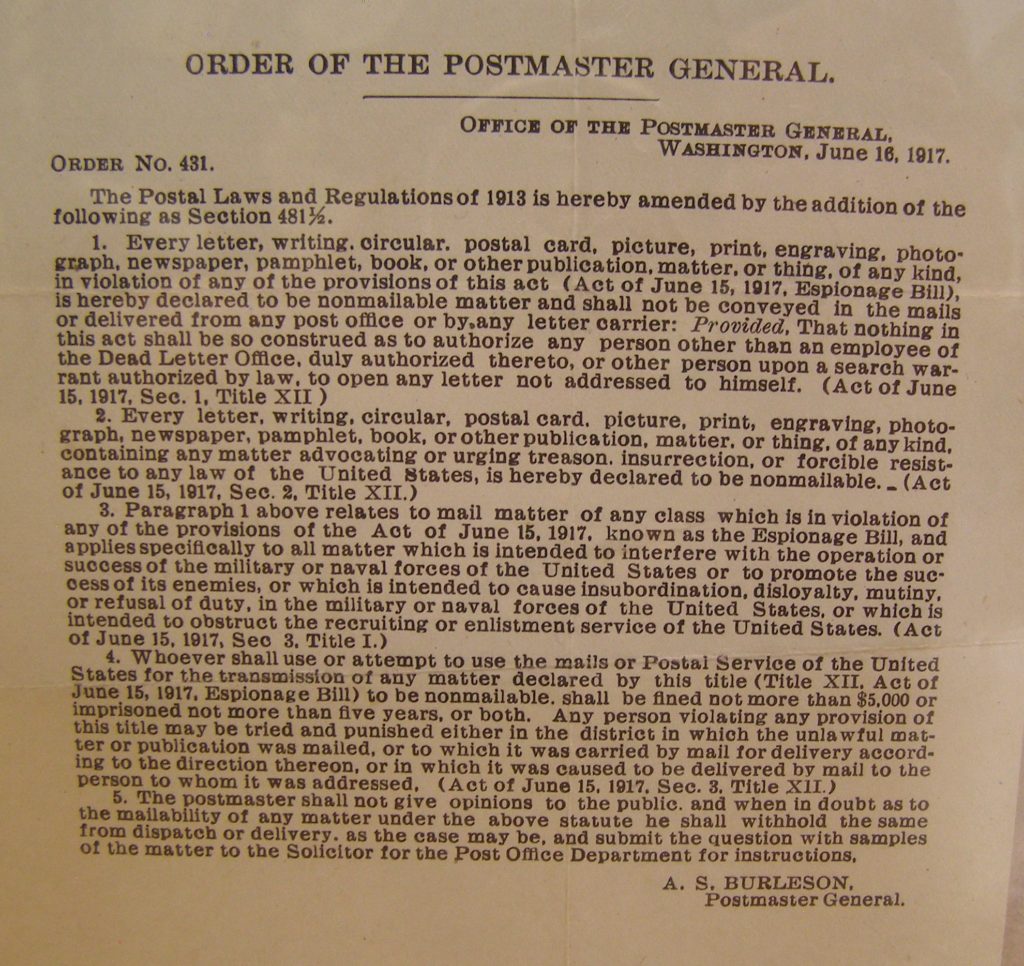

Some of the FLPA arrests had actually taken place earlier. FLPA Secretary Samuel J. Powell was arrested on the 26th of May. [xiv] Interestingly, the Espionage Act was not passed until June 15, 1917; all of the FLPA related arrests and indictments under the provisions of the Act were hence made even before the law was enacted.

“Strong socialist” James Munday, the baseball-playing, Desdemona socialist blacksmith, was among those arrested in the FLPA raids[xv]. Munday, whose wife had died previously, apparently lost his land and moved with his four daughters to a “camp” along the banks of Hog Creek.[xvi]

Tom Hickey, who had no direct affiliation with the FLPA, was arrested without a warrant on May 17t at his wife’s farm in Stonewall County, apparently in an attempt to connect him with the FLPA.[xvii] He was held incommunicado for two days before his wife Clara could find him. Even his attorneys could not make sense of the frivolous charges against him.[xviii]

The socialists in Texas were under surveillance and infiltration.

Tom Hickey’s apprehension of the “peculiar visitor” at one of the baseball games appears to have been well-founded. There is considerable documentation to indicate that the socialists in Texas were under surveillance and infiltration well before the FLPA arrests; there is also evidence noting that the charges against the FLPA were in large part due to the information provided by an undercover operative jointly employed by the government Bureau of Investigation and the James McCane Detective Agency.[xix]

The June 2, 1917 number of The Rebel was the last issue of the paper to be mailed. On June 7, U.S. Postmaster General A. S. Burleson denied the second-class mailing permit of The Rebel under the provisions of the same Espionage Act.[xx] Again, the suppression of the paper on June 7 was before the official enactment of the Espionage Act on June 15, and even before the Postmaster General’s own directive. The Rebel was the first newspaper in the United States shut down by the government for its anti-war activities.

The Socialist Party in Texas had been dealt a crippling blow.

Back in Desdemona, the Desdemona Socialists continued playing baseball.

The team probably never went professional, although some of the players may have gone on to play in the Texas Oil Belt League. There is a Desdemona team listed there in 1919[xxi], which played other local teams in that league from Thurber, Eastland, Ranger, Cisco, Breckinridge, and Abilene — all areas with a considerable socialist presence at that time.

They may have also been morphed into the Eastland Judges team (there was a second-baseman Dillard Payne on the Judges team, who may have been related to the Desdemona Socialist Oliver Payne[xxii]), which played in the West Texas League in 1920. Breckinridge took over the Eastland club franchise in 1921, further diluting any possible Desdemona club membership.[xxiii] In 1924 a later incarnation of the Desdemona team replaced Ranger in the Oil Belt League, which forfeited its participation in the West Texas League.[xxiv]

The fate of Desdemona would change overnight on September 2, 1918.

Oil had previously been discovered and explored in the neighboring communities of Ranger and Thurber; Desdemona barber Shorty Carruth had entertained the notion that there might be oil in and about Desdemona as well. As early as February 2, 1914, he had established the Hog Creek Oil Company and sold shares to his neighbors in Hogtown[xxiv] at $100 a whack; but early drilling efforts had not proven conclusive, investors dropped out, and Shorty pretty much became a local laughingstock.[xxv]

But on September 2, “Shorty’s Hunch”[xxvi] paid off. Working on an oil lease on socialist hard-scrabble farmer Joe Duke’s land in cooperation with Tom Dees, an exploratory drilling hit a gusher and the Desdemona Oil Boom was on.[xxvii] The 109 remaining investors from Shorty Carruth’s Hog Creek Oil Company were called in to ratify the deal and received their first dividend check of $150,000 — a 250% return on their investment.[xxviii]

Dick Carruth, Shorty’s possible relative, struck oil and natural gas on his land and began receiving $1,000 a day in royalties while still advocating for the Non-Partisan League[xxix]. Oliver Payne also hit oil and gas on his property. Uncle Jimmie Ellison struck it big also, and continued his Non-Partisan League membership.[xxx] Dr. Snodgrass got into the act. And the baseball diamond purchased from Dr. Snodgrass by the 50 socialists who wanted a place to play ball became a field of oil derricks and producing wells.

The three Parmer brothers were now worth well over a million dollars each.[xxxi] The Desdemona Socialists had become socialist millionaires.[xxxii] James Munday was among those who became rich; presumably he was able to move away from his camp on Hog Creek.[xxxiii] Old Joe Duke, on whose property the boom started, continued to haul hay and repair his own fences.[xxxiv] There was now the problem of trying to locate all the 50 co-owners of that baseball field to distribute their dividends[xxxv]; many had gone off to war or gone on towards greener pastures before that pasture actually did turn green.

Dr. Snodgrass was unfazed. He still believed he had made a good deal on the sale of that acre and a half.[xxxvi]

Uncle Jimmie Ellison was plagued with his new found success. He found himself besieged by speculators who kept increasing their bids for prospective oil leases on his “flea-bitten sandy” farm in Ellison Springs.[xxxvii]Suspicious, Ellison approached his old comrade Tom Hickey for advice on how to proceed.

Hickey had eventually been released from his unwarranted detention by state and federal authorities in relation to the government detention of the FLPA, even while three FLPA officials — George T. Bryant, Samuel L. Powell, and Zeph L. Risely — had been sentenced to several years imprisonment at Leavenworth. Hickey had made a few attempts to get The Rebel back up and running after its forcible governmental shutdown, but the efforts did not bear fruit. The Socialist Party of Texas was in disarray, still suffering from its war-time persecutions and new internal divisions over the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia. Hickey turned his political attention to organizing for the Texas Non-Partisan League.

Hickey offered to become the general manager of Uncle Jimmie Ellison’s farm, directed the sale of leases on the Ellison property, and almost by default found himself in a new profession. “I carefully aligned myself with the most honest outfit I could find, and thus became vice president of a million dollar oil corporation,” Hickey reported.[xxxviii]

That “most honest outfit” that Hickey could find was the National Workers Drilling and Production Company, which Hickey organized with other socialists in October of 1919: L.L Steele, the one-armed Desdemona socialist school teacher, became President of the new company; W. H. Flowers, an early socialist from Smith County, was named First Vice-President; Hickey became Second Vice-President; and H. W. “Harry” Elliott, the editor of the Desdemona Oil News and elected as the socialist mayor of Desdemona (Tom Hickey was his campaign manager),[xxxix] would become Secretary-Treasurer.

(The one-armed Leslie Lisle Steele holds the distinction of being a fourth-generation socialist in Texas. His great-grandfather, Alfonso Steele, was a member of the Socialist Party of Texas and the last surviving member of the Battle of San Jacinto. Alfonso’s son Hampton was a Socialist Party speaker and organizer during the heyday of the SP in Texas, and L.L. Steele’s father, Leslie Chisum Steele, was the Socialist candidate for county judge in Erath County in 1914. All four are buried in the Mexia City Cemetery)[xl]

In addition to managing the leases of the other new socialist oil operators in the Desdemona area, especially those involved in thecollective ownership of the baseball field, the NWDP soon found itself actuallybecoming a bona fide oil production company. To their credit, they maintained the spirit of collective ownership embraced by their socialist principles and continued to build cooperative stock-holder ownership; Hickey declared this intent with a solicitation to the Non-Partisan League.[xli]

Photo by the author.

The success of the Hickey’s oil company lasted about as long as the Desdemona oil boom. Operating problems emerged as a result of bad management on the part of Elliott and Flowers[xlii]and Hickey resigned in disgust from his position at the company in June of 1920.[xliii]. The company paid off its investors and was sold to the Texas Petroleum Company in September of 1922.[xliv]

And the Desdemona Socialist baseball team faded away as well. A field full of derricks and pumps did not make it conducive to the pursuit of home runs.

The oil bust was not kind to Shorty Carruth. In June of 1923 he was sentenced to a year in federal prison for selling fraudulent oil leases, using a Ponzi scheme to pay >dividends from the sales of unproven leases. He returned to the oil business after he was released and died in Fort Worth in 1931. W.H Flowers also stayed in the oil business, returning to his home in Smith County, where he died in< 1925.

L. L. Steele was another socialist who stayed in the oil business after the NWDP job. He did not go back into teaching, but rather went to law school. Later in life he was named to the Texas Tech University Board of Regents and then to the Texas Highway Commission by progressive governor James Allred. He died in Mexia in 1969.

Hickey continued in the newspaper business, writing for over 14 different newspapers until his death from throat cancer in 1925.

Today Desdemona, like Texas socialism, is a lot quieter than in its boom years.

Footnotes:

[i] For details on the number of encampments and the number of elected officials, see the collected issues of The Rebel 1911-1917 and the Biennial Reports of the Texas Secretary of State.

[ii] The team name appears in “Texas Trails: The past of Desdemona”, Country Worlds on-Line, November 28, 2011; and in “Desdemona”, Clay Coppedge, January 27, 2012, http://www.texasescapes.com/ClayCoppedge/Desdemona.htm

[iii] The Rebel, July 5, 1913

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Boyce House, Were You In Ranger?, Ranger Historical Preservation Society, 1999, p. 61

[vi] Oral History Interview by Richard Mason with Inez Heeter, October 30, 1981, SWCAV0671 and SWCAV0672, Southwest Collection, Texas Tech University

[vii] West Texas Socialists Now Millionaires Oil Well Owners”, Silliman Evans, Fort Worth Star Telegram, August 11, 1919

[viii] Heeter Interview

[ix] Ibid.

[x] The Rebel, May 23, 1914, p.2

[xi] Seminole Sentinel, June 14, 1917, p.6

[xii] See for example the letter of Carl Rosson to Tom Hickey, June 5, 1917, in the Tom Hickey Papers, Southwest Collection, Texas Tech University.

[xiii] “Texas Anti-Conscriptionist…Shot to Death,” Ft. Worth Star Telegram, June 5, 1917

[xiv] Abilene Semi-Weekly Reporter, May 29, 1917, p. 5

[xv] The Farmers’ and Laborers’ Protective Association of America, Robert Wilson, Master’s Thesis, Baylor University, August 1973, p. 88

[xvi] Heeter Interview

[xvii] The Rebel, May 26th, 1917

[xviii] Clarence Nugent to Clara Hickey, July 25, 1917, in the Tom Hickey Papers

[xix] Jeanette Keith, Rich Man’s War, Poor Man’s Fight, University of North Carolina Press, 2004, p. 91, p.220

[xx] Order of the Postmaster General, Order Number 431, June 16, 1917

[xxi] http://baseball.wikia.com/wiki/Oil_Belt_League

[xxii] https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=payne-001dee

[xxiii] The Dublin Progress and Telephone, December 24, 1920

[xxiv] “Glimpses of the Desdemona Oil Boom”, John D. Palmer, West Texas Historical Association Year Book, Vol. 15, October 1939, p.48. The author of this article was a member of the Desdemona Socialists baseball team.

[xxv] El Campo Citizen, August 19, 1919, p.6

[xxvi] Ibid.

[xxvii] Dublin Progress and Telephone, April 18. 1919, p.6, House, Were You in Ranger? p.7

[xxviii] House, Ibid. p.70.

[xxix] Tom Hickey to the Non-Partisan League, n.d., in the Tom Hickey papers.

[xxx] Ibid.

[xxxi] House, p. 70.

[xxxii] “Silliman Evans, “West Texas Socialists Now Millionaires Oil Well Owners,” Fort Worth Star Telegram, August 11, 1919

[xxxiii] Ibid.

[xxxiv] House, p 77

[xxxv] House, p.79

[xxxvi] Ibid

[xxxvii] Frank H. Bartholomew, “Big Fortune Made,” Altoona Mirror (Pennsylvania), November 18, 1922

[xxxviii] Ibid.

[xxxix] Tom Hickey to Clara Hickey, March 15, 1920, in the Tom Hickey papers.

[xl] The activities of the Steele family are documented in the various pages of The Rebel.

[xli] Tom Hickey to the Members of the Non-Partisan League, n.d., in the Tom Hickey papers.

[xlii] “Statement of Facts in the Case of T A Hickey v. the National Workers Drilling and Production Company”, n.d., in the Tom Hickey Papers, Southwest Collection, Texas Tech University.

[xliii] Tom Hickey to W.H. Flowers and H.W. Elliott, June 15, 1920, in the Tom Hickey Papers.

[xliv] Letter to Stockholders of the National Workers Drilling and Production Company, September 26, 1922, in the Tom Hickey papers.

[Steve Rossignol is a retired member of IBEW Local 520 in Austin. He serves as archivist for the Socialist Party USA.]

Another Wob baseball game

The Wobblies’ “March over the Siskiyous” of 1911 began in Portland when local Wobblies joined with the Socialist party to organize over 100 radicals to join a “free speech” fight then going on in Fresno, California. Portland railroad workers in the Brooklyn yards welcomed them to empty box cars on a south-bound Southern Pacific train and friendly city officials and crowds greeted them in Albany, Junction City, Eugene and Roseburg.

But when railroad bulls stopped them in Ashland, the Wobs set out on foot over the Siskiyous range and the California state line in the February snow up to six feet deep and walked almost all of the 150 miles to Red Bluff. In Dunsmuir, CA they challenged the local baseball team and played a friendly game. Finally arriving in Fresno, the Wobs learned the Fresno free speech fight was over and went back to Portland.

In 2010, the Ashland Peace and Justice group launched a campaign for a monument to honor the Wobbly “march.”

More at the late Jay Mullen’s paper delivered at the NW Labor History Assn Annual Meeting

http://www.michaelmunk.com

Correction: The baseball game was in Kennett, CA, a town drowned in the building of the Shasta Dam in the 1930s. The Wobblies played the Kennett baseball team and lost 2-1.

Thanks for posting this, Michael. Very cool little tidbit. We have more history out there than we know!

Steve

Great stuff – keep them coming!

I got a big kick out of this, Steve! It fits right in with the stories in “Grass-Roots Socialism: Radical Movements in the Southwest 1895-1943” by James R. Green (1978). Of course some of the names (e.g., Tom Hickey and “The Rebel” newspaper) are familiar. In the Green book, I was fascinated to read about socialist encampments in Grand Saline (in Van Zandt County)–especially since all I had previously known about Grand Saline was that it (so sadly) became one of the “sundown towns” of East Texas.

If you have more along these lines, please keep it coming, Steve!

Great article. I thought I’d look you up. My name is Terry Harris. I met you working at ThunderCloud subs on Lavaca way back in the late 70’s. You were living in an old house near Dobie Mall. We were in the DSOC together. You left to join and work for the Socialist Party and I lost touch with you.

I still have a house in Austin but presently renting in Santa Fe.

I’ll be returning to Austin mid-June 2020 for a couple of weeks. It would be great to see you again. Always admired your devotion to the cause. HMU if you’d like to visit.

Fascinating stuff. Sorry, did not read this top to bottom, but got the idea. Was researching Thomas A. Hickey who founded the American Association of Professional Baseball Clubs in 1902 and was the league’s president for two extended terms. He died in 1956, so not the same guy, but very cool to know there were TWO Tom Hickeys who were pioneers in the development of the game of baseball on various levels. Also, very interested in knowing more about your organization. In college I wrote about the Populist movement with William Jennings Bryan being one proponent and am now chagrined to hear the word Populist being used to describe the alt-right.

I am trying to connect with Steve Rossignol and hope he will respond via this blog. I study the Boeer/Wolfe family and their fellow German freidenker/socialists who were neighbors of my grandparents in my home community. I volunteer at TX Tech’s Southwest Collection which is posting selected letters from Maria Boeer’s voluminous correspondence with fellow German radicals of the WWI era. Well-known in the socialist movement across the U.S. and in Germany, she exchanged letters with Clara Zetkin, a co-founder of the German Communist Party with Luxemburg and Liebknecht, and also Johan Most’s widow, among many others. I shared with Peter Buckingham Wolfe-related material for his bio of Hickey who presented for me over Hickey and the Boeer/Wolfe family at a conference of the German-Texan Heritage Society. I also shared photos of the Brandenburg, Stonewall Co., Socialists with Tom Alter for his upcoming book about the Meitzens, colleagues of Debs, as was Hickey, who was arrested w/out warrant at his wife’s home in Brandenburg in the 1917 FLPA raid. In the “Red Belt” an indication of the strength of the Party in that German community was that among those buried there is one named after Eugene Debs. In any case, I have a great deal of material I would like Mr. Rossignol to be aware of in particular the posted letters. If anyone has his email please ask him to contact me via LinkedIn or respond in this blog.

Does Steve Rossignol stllllive in Blanco, TX?