The CPUSA was the only predominantly white organization to make anti-racism a major priority.

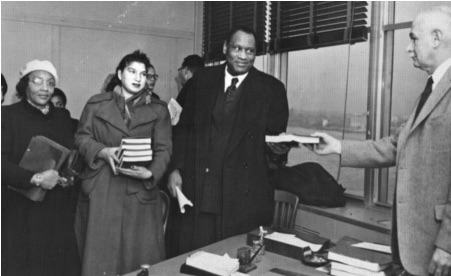

Paul Robeson presents “We Charge Genocide” by William Patterson to UN Secretariat in New York, December 17, 1951.

ROYALSTON, Mass. — When I read the news a few weeks ago that Philonise Floyd, the brother of George Floyd (the Black man killed by police in Minneapolis), went to the United Nations to call attention to racial injustice in the USA, a three-word memory from my childhood popped into my head: “We Charge Genocide.”

I was only 10 years old in 1951, when two Black men, William L. Patterson and Paul Robeson, presented a petition on the topic of racial injustice to the United Nations in both Paris and New York.

The petition was entitled “We Charge Genocide: The Crime of the Government Against the Negro People.” Patterson, credited as the author, was secretary of the Civil Rights Congress (CRC), and presented the petition in Paris on behalf of his organization, while Robeson brought it to the UN headquarters in New York City.

The language of the petition is chilling and powerful. Consider this paragraph:

Once the classic method of lynching was the rope. Now it is the policeman’s bullet. To many an American the police are the government, certainly its most visible representative. We submit that the evidence suggests that the killing of Negroes has become police policy in the United States and that police policy is the most practical expression of government policy.

The petition listed 152 incidents of killings and 344 other acts of violence.

The 78-page petition listed 152 incidents of killings and 344 other acts of violence — between 1945 and 1951 — that the CRC offered as evidence. The petition, signed by 94 individuals, sought to demonstrate that the government of the United States was in violation of the UN Genocide Convention. The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide had been adopted in 1948 in the aftermath of the Holocaust.

The University of Washington’s Mapping of American Social Movements Project has published a detailed article on this topic by Susan Glenn, entitling it “The 1951 Black Lives Matter Campaign.” Here is the link.

Patterson was a member of the Communist Party (CPUSA) and the CRC was associated with the Party, too. This helps explain why I, a white man, remember this moment in 1951. My parents, Rae and Louis Young, were also members of the CPUSA. Their bookshelves included many books published by International Publishers, affiliated with the CPUSA, and they subscribed to left-wing newspapers including the Party‘s Daily Worker and the independent but pro-Communist National Guardian. At 10, I was a good reader and my parents encouraged my interest in politics. There’s more about my childhood experience and its significance later in this article.

It was the policy of the Party to encourage Black people (called Negroes in those days) to join the party. Whites and Blacks worked together under the auspices of the Party to bring attention to racial justice issues, as well as to celebrate African-American culture. Regarding the word “Negro,” one thing I recall from those times is that the word was not capitalized in most newspapers and periodicals while the Communists were adamant about using and advocating for the upper case “N.” Use of this word has clearly become a thing of the past.

Remarkably, the CPUSA was the only predominantly white organization to make anti-racism a major priority in the 1930s and 1940s and into the 1950s, too. In fact, some Black leaders of the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s had been Party members or at least had contact with members.

Historians known to be members of the CPUSA were pioneers in the field of Black history.

Historians known to be members of the CPUSA, including Philip Foner, Herbert Aptheker and James S. Allen, were pioneers in the field of Black history. Pulitzer Prize winning historian Eric Foner (the nephew of Philip Foner) wrote about this in his book, The Story of American Freedom.

Some readers of this blog might be skeptical about the CPUSA promoting the issue of genocide when it comes to African-Americans in the USA, because of the Communists’ enduring admiration of Stalin. Historians have documented the killing of millions by Stalin’s regime, but the CPUSA would have none of it. The revelations by the Soviet Union’s Nikita Khrushchev did not come until 1956, three years after Stalin’s death and five years after “We Charge Genocide.”

I offer three reasons for this. First, the Communist rank-and-file, including my parents, accepted the idea that anything negative about the USSR was “bourgeois propaganda,” ironically, an attitude similar to the current “fake news” cry from the Trump camp. Second, Communists liked praising the Soviet Union as America’s war-time ally against Hitler, pointing out the deaths of millions of Russians and courage of more millions in the anti-Nazi effort. And third, Communists honored the USSR as “the world’s first socialist nation.”

As I read the 1951 petition, I perceived a connection to lists we’ve been seeing recently of Blacks who were victims of racist violence. The #SayTheirNames campaign encourages publications and social media users to not just identify victims of police brutality by the incidents that killed them but to focus on their individual humanity and use their names. The hashtag is often accompanied by lists of names of Black men and women killed in recent years, including Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Philando Castile, Breonna Taylor and many others. The 1951 “We Charge Genocide” petition to the UN terminated with these three name-filled paragraphs:

We want the General Assembly to know of Willie McGee, framed on perjured testimony and murdered in Mississippi because the Supreme Court of the United States refused even to examine vital new evidence proving his innocence. But we also want it to know of the two Negro children, James Lewis, Jr., fourteen years old, and Charles Trudell, fifteen, of Natchez, Mississippi who were electrocuted in 1947, after the Supreme Court of the United States refused to intervene.

We want the General Assembly to know of the martyred Martinsville Seven, who died in Virginia’s electric chair for a rape they never committed, in a state that has never executed a white man for that offense. But we want it to know, too, of the eight Negro prisoners who were shot down and murdered on July 11, 1947, at Brunswick, Georgia, because they refused to work in a snake-infested swamp without boots.

We shall inform the Assembly of the Trenton Six, of Paul Washington, the Daniels cousins, Jerry Newsom, Wesley Robert Wells, of Rosalee Ingram, of John Derrick, of Lieutenant Gilbert, of the Columbia, Tennessee, destruction, the Freeport slaughter, the Monroe killings — all important cases in which Negroes have been framed on capital charges or have actually been killed. But we want it also to know of the typical and less known — of William Brown, Louisiana farmer, shot in the back and killed when he was out hunting on July 19, 1947, by a white game warden who casually announced his unprovoked crime by saying, “I just shot a n—r. Let his folks know.” The game warden, one Charles Ventrill, was not even charged with the crime.

In considering the consistent and admirable anti-racist stance of the CPUSA, the case of the Scottsboro Boys, two decades prior to “We Charge Genocide,” is relevant. Wikipedia’s summary of the case is a good place to start:

The Scottsboro Boys were nine African American teenagers, ages 13 to 19, falsely accused in Alabama of raping two white women on a train in 1931. The landmark set of legal cases from this incident dealt with racism and the right to a fair trial. The cases included a lynch mob before the suspects had been indicted, all-white juries, rushed trials, and disruptive mobs. It is commonly cited as an example of a miscarriage of justice in the United States legal system.

Following the trial of the Scottsboro boys, an appeal (with mixed results) was filed with the support of the CPUSA and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

I recommend an excellent documentary video entitled Strange Fruit.

Early in my youth, I learned about the Scottsboro Boys, and I’m sure other red diaper babies had the same knowledge. It was during my childhood that I learned names like Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, Nat Turner, Sojourner Truth, and Langston Hughes. I learned about lynching, and I heard the song Strange Fruit, written in 1937 by a Jewish communist and teachers’ union member, Abel Meeropol (pen name Lewis Allan). Abel and his wife Anne adopted the orphaned sons of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. I recommend an excellent documentary video entitled Strange Fruit. Listen to Billie Holiday sing the song at this site.

On the topic of lynching, I want to bring up another moment in history which I learned about recently while reading the biography of Eleanor Roosevelt by Blanche Wiesen Cook. In the mid-1930s, when Franklin D. Roosevelt was president of the USA, the NAACP endeavored to have Congress pass a Federal anti-lynching law, as these crimes were happening often and the perpetrators were never charged. The NAACP won the support of Eleanor Roosevelt, the First Lady at the time, but she could not get her husband to take a stand. He claimed he could not afford to lose the support of Southern Democrats. Communists, of course, supported the effort.

Regarding our experience as the children of Party members, my college friend and fellow Rag Blogger Jonah Raskin, offered this comment:

As the son of Communist Party members, I grew up in the 1940s and 1950s knowing a great deal about slavery, the resistance to it, along with Jim Crow laws and the civil right movement. Had I been born to parents not in the CP, I am sure that I would not have learned the same historical record. Other sons and daughters with CP parents had the same or similar experiences. I prefer not to use the phrase, ‘red diaper baby’ to describe us. To me it’s demeaning.

As a teen, I read books by authors who were in the CP or were close to it, including Howard Fast, before he became a sell-out. My parents welcomed blues singers into our home. My college roommate, Eric Foner, had lefty parents, and grew up knowing about African-American scholars such as W. E. B. DuBois and African-American artists like Charles White. So I received a double whammy so to speak, from my parents and from Eric’s parents who welcomed me into their home and treated me like one of the family. That was another benefit of the culture of the Old Left. The door was always open. A place always set at the table.

Those of us with Communist and other leftist backgrounds felt a special bond.

My experience was similar. In many ways, those of us with Communist and other leftist backgrounds felt a special bond. I wrote about this in my 2018 autobiography, Left, Gay & Green: A Writer’s Life. In the book, I tell a story which is relevant to this article, one that many readers find quite amusing, so I’m inserting it here:

I remember once, at age ten or eleven, hiding behind a hedge along Riverside Drive in New York City with Michael Lessac. We were usually good boys, but this time, to entertain ourselves, we had water pistols and were squirting people who walked by. But when a Black woman walked by, neither of us squirted. Later, we had a discussion about which was the right thing to do: show our belief in equality by squirting the Black woman the same way we squirted white people or refrain from squirting because we knew she was a victim of racism. You could say our decision not to squirt was an early version of affirmative action.

Getting back to “We Charge Genocide,” it got a lot of attention in Europe but did not result in any helpful action for African-Americans, largely due to the predominant Cold War and Red Scare environment. Even the NAACP shied away from endorsement. The UN did not acknowledge receiving the petition. Patterson had his passport seized by the government and was later jailed under the anti-Communist Smith Act. Here’s more from Wikipedia:

We Charge Genocide was ignored by much of the mainstream American press, but the Chicago Tribune, which called it “shameful lies” (and evidence against the value of the Genocide Convention itself). I. F. Stone was the only white American journalist to write favorably of the document. The CRC had communist affiliations, and the document attracted international attention through the worldwide communist movement. Raphael Lemkin, who invented the term “genocide’”and advocated for the Genocide Convention, disagreed with the petition because the African-American population was increasing in size. He accused its authors of wishing to distract attention from the alleged ‘genocide’ in the Soviet Union, which had resulted in millions of deaths, because of their communist sympathies. Lemkin accused Patterson and Robeson of serving foreign powers. He published an op-ed in the New York Times arguing that Blacks did not experience the “destruction, death, annihilation” that would qualify their treatment as genocide.

I began this article with reference to George Floyd’s brother going to the UN. According to a report in Politico, Philonise Floyd “addressed a special meeting of the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva, Switzerland via video address, telling the assembled diplomats “my brother tortured and murdered on camera is the way Black people are treated by police in America.”

“I am my brother’s keeper” Floyd continued. “You in the United Nations are our brothers’ and sisters’ keepers. I am asking you to help me get justice.”

The Politico article reports that during the Council gathering, many nations blasted the racism of the U.S., while others spoke of racism as a global issue. The U.S. itself was not present because President Donald Trump had our nation pull out of the Human Rights Council in 2018. You can read the Politico report here.

I conclude with a personal comment. I am not claiming that my childhood experiences mean I’m fully enlightened on the issue of racism. It’s an ongoing effort, and it’s encouraging to see that growing numbers of white people are becoming more involved in this movement. I remember when I first heard the term “white skin privilege.” It was in the late 1960s at a gathering of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). The concept made me feel a little uncomfortable, but it was food for thought, and I learned from the ensuing discussion. I continue to learn and am aware of the varied ways racism infects all white people and doesn’t magically go away because we attend a march, read a book or write for a blog.

[Allen Young has lived in rural North Central Massachusetts since 1973 and is an active member of several local environmental organizations. Young worked for Liberation News Service in Washington, D.C., and New York City, from 1967 to 1970. He has been an activist-writer in the New Left and gay liberation movements, including several items published in The Rag Blog. Retired since 1999, he was a reporter and assistant editor of the Athol (Mass.) Daily News, and director of community relations for the Athol Memorial Hospital. He is author or editor of 15 books, including his 2018 autobiography, Left, Gay & Green; A Writer’s Life — and a review of this book can be found in The Rag Blog archives.]

- Read more articles by and about Allen Young on The Rag Blog.

That all said, one small note on Fred Douglass, per the new, as of 18 months ago or so, bio of him.

He thought, like whites of his time, that American Indians needed to all become good white farmers, and also good “Americans” socially, or die off.

It is wonderful to see my dear friend Allen Young’s piece on WE CHARGE GENOCIDE. I was just like him, Jonah and Eric (and many others) who were exposed to black history at an early age. One of the books that was most educational for me was Howard Fast’s FREEDOM ROAD which inoculated me to the racist interpretation of Reconstruction after the Civil War — the interpretation that dominated the study and teaching of American History till almost the end of the 1960s. I was too young to read DuBois’ BLACK RECONSTRUCTION but the novelist’s treatment by Fast gave me enough information about the short period of “true democracy” in the American South when the 14th and 15th Amendments were actually made effective by the Federal Government. For most Americans, the historical understanding that us “red diaper babies” experienced, had to wait till well into the 1970s.