The underground press was everywhere you looked: on campus and off, in urban, suburban, rural, ghetto, barrio, in every state of the Union.

[This is the third of a three-part series written for The Rag Blog by underground press historian Ken Wachsberger. Part I was about the 50th reunion of the Berkeley Barb and Part II featured a similar event honoring Detroit’s Fifth Estate.]

What was the countercultural underground press?

In the first two parts of this series I have referred to the “countercultural” underground press as opposed to just the more commonly known “underground press.” The term isn’t meant to disparage the storyline that begins with Art Kunkin founding the Los Angeles Free Press in 1964, followed by the East Village Other, the Berkeley Barb, The Paper, and the Fifth Estate in 1965; The Rag, the San Francisco Oracle, Illustrated Paper, and Underground Press Syndicate in 1966; and then the explosion.

The Rag Blog’s Thorne Dreyer, who was a founding editor of The Rag in Austin and Space City! in Houston, is a proponent of this storyline:

In the early days, when papers exploded across the country, there was definitely and clearly an “underground press” that papers identified with and considered themselves a part of. And that common sense of identity and purpose was one of the reasons they grew so fast.

The underground papers, though they varied greatly, shared a general philosophy that grew out of the sixties psychedelic culture and New Left politics. (And an irreverence inspired by the likes of Paul Krassner’s Realist.) They had an often explicit commitment to common cause with the other papers, and were usually multi-issue, as opposed to the doctrinaire left papers and those, like the gay, women’s, and GI papers, that focused primarily on specific communities and causes. The original underground papers actually created a model for and often provided material assistance to the later publications

The distinctions blur, of course. They overlapped and were all part of a larger phenomenon. And my view is certainly open to debate!

I’m a proponent of this storyline, too. My roots are defined by it. It’s exciting — okay, a bit white, but it was what it was, never for evil intentions, and always with the noblest goals of forging alliances, bringing people together, and striving to live lives at a higher level of consciousness with more laughter and better music for dancing.

I was from day one seeing the broader definition of the underground press.

But being further removed from ground zero than Thorne, having not become part of the underground press myself until December 1970, I was from day one seeing the broader definition — the blurred line, perhaps — as including papers that by now represented the feminist, minority, LGBT, and other alternative voices that were by then becoming so well defined.

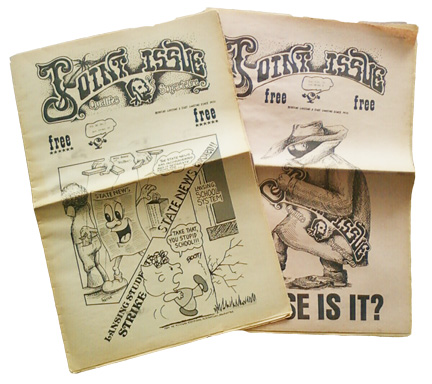

When the mail carrier brought copies of other UPS-member underground newspapers to the Joint Issue office, I read them all, cover to cover, including Fag Rag and Gay Liberator, representing the post-Stonewall gay voice; Akwesasne Notes, one of the most influential newspapers of the Native American radical community; off our backs, the first nationwide feminist newspaper to emerge on the east coast; and underground newspapers representing other voices that I never read in the mainstream, corporate newspapers.

I came to see that the underground press was everywhere you looked, far more extensive than any of us who were involved with it could imagine at the time: on campus and off, in urban, suburban, rural, ghetto, barrio, and other communities in every state of the Union and in countries around the world.

The papers represented the gay, lesbian, feminist, black, Native American, Chicano, Puerto Rican, Asian American, prisoners’ rights, military, New Age, socialist, anarchist, psychedelic, high school, disability rights, senior citizen, rank and file, Southern consciousness, and other alternative voices of the day. They were found in every branch of the military — over 900 GI underground papers. And therein law the power of the underground press.

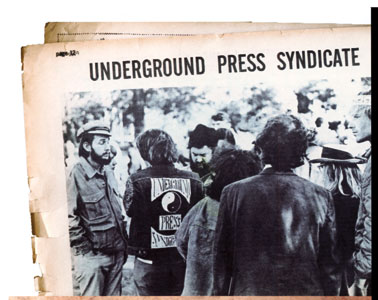

First meeting of the underground press at Stinson Beach, California, March 1967. At left is The Rag’s Thorne Dreyer.

To Thorne, the underground press was a genre within the larger category of alternative press:

I believe the “underground press” was a unique and definable phenomenon within the larger context of an explosion of alternative publications generated by the advent of the offset press and the social movements of the day.

I agree. But pressed tightly against that blurred line in 1970, I often couldn’t tell where one paper stopped being underground and started becoming alternative because they shared too many of our characteristics even if not all of them. So today my broader definition of “underground” includes qualifying descriptors, or genres: the feminist underground, the LGBT underground, the GI underground, the minority underground, and others.

While Thorne calls the underground press a subset of he broader alternative press, I call the countercultural underground press a subset of the broader underground/alternative press — what Thorne referred to as the “larger phenomenon.” Either way, it had its own unique, exciting, important story, one told so well in John McMillian’s Smoking Typewriters and without which the concept of “fiftieth anniversary” would be meaningless.

Which papers could wear the label and which couldn’t? When did it end? No one has adequately answered those questions yet. But clearly the countercultural underground press was part of this broader family of independent, noncorporate newspapers whose stories begin much earlier than 1964 and continue today, and which together led the way in ending the Vietnam War and raising the issues that brought the liberation movements into the mainstream.

For instance, the Stonewall Rebellion of 1969 inspired gays and lesbians all over the country to establish local Gay Liberation Front chapters, many of which had their own papers: Fag Rag in Boston, Gay Sunshine in San Francisco, and Gay Liberator in Detroit, to name just three. Certainly they were inspired by the Los Angeles Free Press storyline.

But by the end of the fifties, there already were two major gay papers (ONE and Mattachine Review) and one major lesbian paper (The Ladder) that also had a major influence on the GLF papers. In fact, the first GLBT paper of our era is generally considered to be Vice Versa, a short-lived mimeo’d newsletter (not a tabloid) founded in 1947 by Edythe Eyde, writing under the pen name Lisa Ben (wordsmiths can combine the two words and rearrange the letters to find her hidden message).

Important black papers also pre-dated the Free Press. The Student Voice, the paper of SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), began publishing in 1960. Freedomways, founded by W.E.B. Du Bois and others, began the next year. Paul Robeson founded his paper, Freedom, during the Korean War.

As we glorify the very real fiftieth anniversary of the countercultural underground press, it is important that we not limit our discussion in a way that fails to acknowledge these publications and others like them. Together they were more than a family of genres. They were a major force.

The underground papers of the Vietnam era spoke to their own unique audiences.

The underground papers of the Vietnam era spoke to their own unique audiences but they were all passionately united against the war and in favor of the emerging counterculture and its related liberation movements, though they all struggled to visualize and define their versions of an ideal society and the versions didn’t always agree. They were underground in attitude and in irreverence, and probably were influenced by psychedelics. They all used the tabloid format for their layout.

Every paper fit this description in part; few fit it completely.

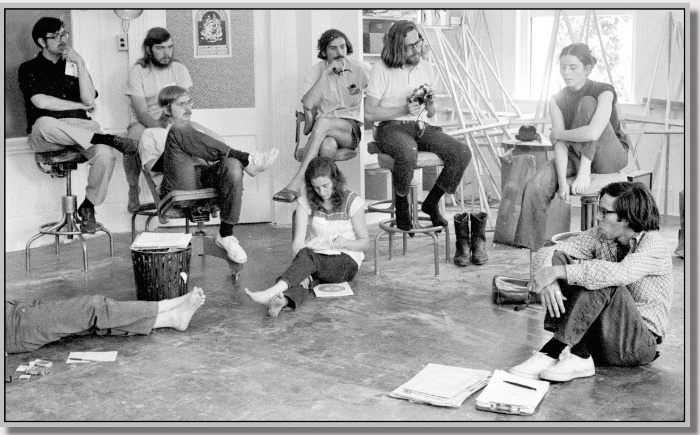

In the summer of 1973, a conference was held in Boulder, Colorado, hosted by the local underground newspaper Straight Creek Journal. The 150 attendees represented over 50 underground papers, including many from UPS. Each was financed in its own unique way. One staff I remember financed their paper by selling pot, but never heroin or speed. Other papers guilt-tripped rich liberals into supporting them or found rock groups to hold fundraising concerts.

Some papers, like Lansing’s Joint Issue, Madison’s Free For All, and Columbus, Ohio’s Columbus Free Press, had a strong enough community base that they could finance publication in part or in whole through ad sales to progressive businesses and then give away the paper for free. Others, like Fifth Estate, prided themselves on being reader-supported.

One way or the other, they got the money because the papers were more than labors of love. They were mission-oriented, and that mission was politically, economically, artistically, spiritually, and culturally anti- the officially sanctioned viewpoint of the corporate press. And that was what had made them underground.

But by 1973, increasing numbers of Americans had come around to our antiwar arguments, and the government was being forced to wind down the war. Ideas that had appeared first in the underground press were everywhere on the pages of the corporate press, which, of course, were claiming the stories as their own. For instance, release of The Pentagon Papers by Daniel Ellsberg nearly scandalized the government and inspired charges of “treason” because of the supposed sensitivity of the information; in fact, the substance of those revelations had long been known by readers of the underground press.

Our ideas were no longer underground in

even a romantic sense.

What we discussed at the conference was that our ideas were no longer underground in even a romantic sense. A vote was taken and it was agreed to change the name of Underground Press Syndicate to Alternative Press Syndicate. The underground press of the Vietnam era in name ceased to exist.

By this time some papers that looked like undergrounds already had started using the term “alternative” to describe themselves, often as part of their emerging campaigns to go legitimate, achieve stability, attract the attention of potential advertisers, plan for the long haul, take themselves seriously, make money.

These papers led the way in toning down their look and feel from the raw grittiness of the founding papers. Content was more likely to be liberal, a demeaning term that came to mean it appeared to be headed toward a radical conclusion but then pulled its punches at the last minute so as to not offend advertisers — as liberal politicians did to not offend wealthy donors. Photos were more likely to be square and rectangular. Text was less likely to be running up and down the margins shouting slogans of solidarity and inspiration, like

- Free Huey

- Boycott Grapes and Lettuce and All Wines from Modesto

- Smash the State

- Pick Up Hitchhikers

- Sisters Pick Up Sisters

- Tip the Dishwasher

- Chop Down Cars

While our ideas had gone mainstream, not everybody liked them. The period divided and traumatized our country like no period since the Civil War. By the time the period came to an end, roughly the time the war ended, activists of the antiwar movement had turned inward and embraced the Me Decade.

Meanwhile, the country swung dramatically to the right. Vietnam was “disappeared” from history. Even today, high school and college history courses gloss over it while ignoring the role of the antiwar movement in bringing it to an end. Journalism classes ignore or downplay the place of the underground press in the history of journalism. Political blogs have taken up the tradition that we carried on in the fifties through the eighties but most young bloggers have no idea of their political roots.

When the first edition of my Voices from the Underground Series was coming out in the early nineties, Art Levin, who was the general manager of Michigan State University’s State News during the time I wrote for Joint Issue, wrote:

The period of the late sixties and early seventies was a high water mark for American journalism. For the first time in American history, the vision of Justices Holmes and Brandeis blossomed and bore fruit. A multitude of voices, the essence of democracy, resounded through the land providing a compelling alternative against the stifling banality of the establishment press. What this nation had during the Vietnam War was exactly what the founding fathers understood the press to be all about when they wrote the First Amendment.

Fifth Estate’s Peter Werbe is critical but cautiously pleased when he assesses the value of the underground press today:

I don’t care that the mainstream media picked up on the youth culture or started running unjustified copy that ran around graphics, or that they looked to us for story leads. They still are boring and run constant lies about everything that matters. That hasn’t changed a bit. I think the ‘60s underground press has little significance for today since there has been a disconnect of several decades between what we published and current efforts, although when people, young and old, see our exhibits, it seems to give them profound joy to know there was such resistance to a murderous war and a paper that, as the FBI report said in 1970, “supports the cause of revolution everywhere.” And we still do.

Diana Stephens is more positive:

We stressed the similarities between the underground press in the sixties and today’s Internet. When you really start to examine those old headlines and stories, you can see that the issues of importance back then are still being discussed in the media today. Matters of equality, the war machine, police brutality, the environment, individual rights v. government and societal controls, etc. Fifty years later we are still struggling with many of the same issues; these aren’t new and people need a better understanding of the times.

It is an inspirational, empowering history that needs to be brought to the attention of current and future generations so that they may feel, as Peter says, “profound joy” at the possibility of resistance. May the reunions be only the beginning of a new renaissance of awareness and possibility.

The Rag, Austin’s pioneering underground newspaper founded in 1966, is having a public celebration and staff reunion (“50 Years and Still Raising Hell!”) on Oct. 14-16, 2016, in Austin, that will include exhibits, concerts, panel discussions and presentations, the premiere showing of a documentary film about the paper’s history, and the unveiling of a book with art and articles from the original Rag, as well as substantial new material. Details and venues are to be announced.

The Rag, Austin’s pioneering underground newspaper founded in 1966, is having a public celebration and staff reunion (“50 Years and Still Raising Hell!”) on Oct. 14-16, 2016, in Austin, that will include exhibits, concerts, panel discussions and presentations, the premiere showing of a documentary film about the paper’s history, and the unveiling of a book with art and articles from the original Rag, as well as substantial new material. Details and venues are to be announced.

Find more articles about the underground press on The Rag Blog and interviews about the underground press on Rag Radio.

Find articles by and about Ken Wachsberger on The Rag Blog.

[Ken Wachsberger is a long-time writer, editor, political activist, and member of the National Writers Union. He is the editor of the four-volume Voices from the Underground Series and a driving force behind Independent Voices, Reveal Digital’s underground press digital project.]

One difference between then and now for me was the solidarity of working together on actual machinery. I worked for SDS Liberation Press and for a long time we had an old Chief 10 Press and a Multilyth. There was a camera and a darkroom, a folder and hand collating. We worked long hours especially during the 68 convention when we put out the wall poster “the handwriting on the wall.” Part of the Chicago surrealist group, I worked on wall poster “surrealist insurrection.” Urban renewal left plenty of places to post these things so they were in the face of the general public. We had a public presence. New Left Notes was mailed everywhere in stacks. Our Solidarity Bookshop on Armitage Avenue carried all the underground papers including Black Panther and Situationist mags from Paris. We published “Rebel Worker” and came up with the slogan “make love, not war.” Splendid times, only wish we had made that revolution then and avoided this endless round of racism and war.

Very glad we still have The Rag and Fifth Estate.

Interesting that the experiences of the left generation of the 30s was largely lost to the “New Left” of the 60s.

This is an artifact, most historians say ,of the Red Scare repression and the post-Stalin regrets of the US old left.

Now, as this article says, much the same act of memory repression has occurred with legacies of 60s leftism, even without an overt legally repressive counter-movement, like McCarthyism, to launch fresh purges

We all forgot, to a great extent, just what happened when and why.

Forgetting on the mass level may serve as some kind of necessary function to stabilize a society after such a intense, disruptive period.

I think the pervasiveness of the various papers indicates that solidarity doesn’t have to be based on a specific text like Das Capital, even though such blueprints help, but its a feeling in the air that is contagious and captures everybody.

I did a whole lot of artwork for the Joint Issue… plus designed the masthead.