‘The book is a valuable resource, offering readers an excellent…overview of what the 1960s counter-culture and political movements…were all about.’

This article was first published in The Sixties: A Journal of History, Politics and Culture, Vol 9, No 2, and was published on The Rag Blog, April 28, 2017.

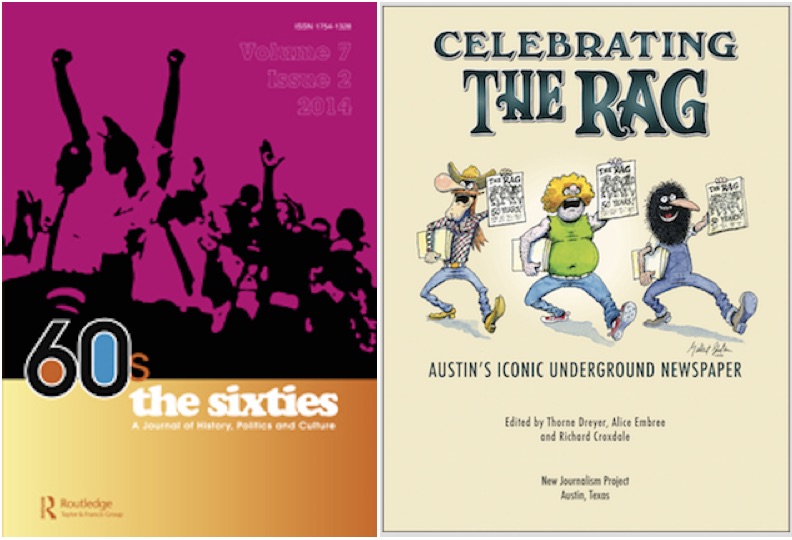

Celebrating The Rag: Austin’s Iconic Underground Newspaper, edited by Thorne Webb Dreyer, Alice Embree and Richard Croxdale, designed by Carlos Lowry, Austin, TX, Lulu, 2016, 316 pages, US$25.00 (paperback), ISBN-10-1365390543

Here are some of the words and phrases used by veteran radical journalist Thorne Webb Dreyer, to describe the underground press of the 1960s: “raggedy upstart newspapers,” legendary, trailblazer, freaky, raving, irreverent, revolutionary and more (4).

“And one uppity little tabloid way down yonder in Austin, Texas, would be a very influential player in the rich if relatively short-lived odyssey of the underground press,” Dreyer proclaimed in the first chapter of Celebrating the Rag. (4)

In October of 2016, I traveled to Austin to attend the 50th anniversary celebration of The Rag, published from 1966–1977. The reunion included the release of an impressive 8 ½ by 11 inch, 300-page book entitled Celebrating the Rag: Austin’s Iconic Underground Newspaper. The book is a valuable resource, offering readers an excellent and complete overview of what the 1960s counter-culture and political movements of the era were all about, while also providing unique insights into the life and people of Austin, a relatively small city. Now a growing metropolis, Austin served then and still is the state capital, the home of the University of Texas, and a regional cultural mecca.

I learned long ago, when I attended national meetings of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), not to stereotype the south and especially Texas. Here, where I live in Massachusetts, unfortunately, the stereotype of “Texas rednecks” remains as strong as the stereotype in Texas of “Massachusetts liberals.” This book is enlightening for those who perpetuate stereotyping.

The Rag! I can readily imagine the founders laughing, perhaps stoned from smoking marijuana, when that name was chosen! The name alone is indicative of the counter-culture sensibility that distinguished the underground press from both the establishment press and Old Left periodicals such as the Daily Worker and New Masses. It also hints at the role of humor and the lack of self-aggrandizement.

How appropriate then, that the book cover features the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers celebrating “The Rag…50 Years!” These are the iconic cartoon characters created by Gilbert Shelton and launched on the pages of The Rag in 1968. True fans of the brothers know all three of them by name — Freewheelin’ Franklin Freek, Phineas Phreak and Fat Freddy Freekowtski — each with his own characteristics. (The brothers have their own Wikipedia page, if you want to know more.) Here is one of the most enduring lines from Freewheelin’ Frank: “Dope [pot] will get you through times of no money better than money will get you through times of no dope.” This was Rag cover art Oct. 18, 1971, and appears on 107 of the book.

In the back of the book, where each contributor has a paragraph, Shelton is described as “A Houston native who, with Robert Crumb, was arguably the most famous underground comix artist of the ’60s and ’70s. The Freak Brothers strip which was reprinted in underground and alternative publications around the world, still has an international following, has been translated into multiple languages, and has now reached tens of millions of readers.”

(There was no pot at the reunion I attended, by the way, just lively old folks’ chit-chat mixed with serious politics.)

After all, serious politics, not pot or acid, was the foundation of The Rag, as evidenced throughout the book. Rag staffers personified the saying “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy,” but despite the comics and the fooling around, this book clearly indicates how much hard work went into chronicling the struggles for social justice and political changes in the 1960s. The Rag was published, its staffers claimed, apparently quite accurately, as a “miracle of functioning anarchy.”

I have used the terms activist journalism or advocacy journalism, and even propaganda, “in the good sense of the word — to propagate good ideas” to describe my own evolution as a writer. My personal link to The Rag began in 1967 when I quit a coveted job as a Washington Post reporter to join Liberation News Service (LNS), which sent material to the hundreds of so-called underground papers that sprang up around the USA.

These papers were popular with college students, hippies, open-minded intellectuals and others, and their focus may have included the absurdity of the laws prohibiting marijuana, but mostly these papers were about opposition to the Vietnam War, racism, lack of free speech and other timely issues. We at LNS always enjoyed looking at The Rag when it came to our office, as it was creatively edited and often used our material, a fact mentioned in the book.

The articles in this volume, reprinted from The Rag, cover an array of topics, including local high school and college controversies, abortion rights, legalization of prostitution, labor strikes, farm workers, gay liberation, South African apartheid, environmental politics including nuclear pollution and organic farming, a free health clinic, musical bands and GI opposition to the war. Fort Hood, located 75 miles from Austin in Killeen, Texas, was a focal point for antiwar activity. Articles cover the persecution of antiwar soldiers and the work of the Oleo Strut coffee house, part of a national network of similar coffee houses reaching out to GIs with an antiwar message.

While The Rag reported on black civil rights issues, including police brutality and the rise of the Black Panther Party, the paper apparently avoided two words from the Black Panther lexicon—“pigs” and “Amerikkka”—that were used excessively by others. This vocabulary usage is a subject I am exploring myself in an autobiography I am currently writing.

In a similar vein, reflecting my concern about dogmatism and excessive zeal, I appreciated Rag articles that allowed varied points of view in the same paper. There was one well-reasoned piece on a split between two Hispanic candidates, Democrat Gonzalo Barrientos and Armando Gutierrez of the radical Raza Unida. Another pair of articles on the intrinsic worth of electoral politics was a “yea” essay (by Gavan Duffy and Mariann Wizard) and a “nay” commentary (by Jim Simons).

People looking back at the 1960s will benefit from analytical pieces in this book, including Harvey Stone on demonstrations at the 1968 Democratic convention, Gary Thiher on the 1969 Woodstock music festival in New York State, and Sharon Shelton-Colangelo on The Rag and women’s liberation — to cite just a few. Rag staffers praise themselves on their early “embrace of feminism,” (97) and the book includes a piece by Bea Durden (June 30, 1969), which is essentially an introduction to women’s liberation for those who needed it (most readers back in that day, probably).

Photographs of 1960s cultural and political icons, all reproduced from Rag pages, can be found throughout the book. They include Bob Dylan, Janis Joplin, Frank Zappa, Allen Ginsberg, Jane Fonda, Pete Seeger, Stokely Carmichael and others. I also learned about individuals I had never heard of before. Lee Otis was a local black student leader who was sentenced in 1968 to 30 years in prison for passing a marijuana cigarette to an undercover officer. Judy Smith, a Rag staffer and feminist who died in 2013 and who is the subject of a few remembrances, founded the Austin Women’s Center and had a significant role in the case of Roe v. Wade. Larry Caroline was a philosophy professor, outspoken against the Vietnam War and fired by then University of Texas dean John Silber. Silber’s name popped out of the page, because I knew him later on as the nasty authoritarian president of Boston University and Democratic candidate for governor of Massachusetts. Silber lost that election in 1990 because thousands of liberals and leftists, including me, voted instead for the moderate Republican William Weld.

The introduction to the book calls attention to the art that “sizzled and entertained” (1). Some of it is quite beautiful, especially the intricate armadillo drawings of Jim Franklin, but some seem messy, perhaps due to the size reduction required by the book size compared to the tabloid size of The Rag. Carlos Lowry, the husband of coeditor Alice Embree, did a nice job of designing the book. (Just a personal touch: The couple met as fellow activists in the struggle against the Augusto Pinochet dictatorship in Chile.)

I appreciated a reference to the street vendors who sold The Rag. These vendors are an oft-forgotten piece of the underground press story. Some people actually made a living doing this, and street sales were important to the success of the papers. Also vital was advertising, and some Rag ads are reproduced. One advertisement especially amused me, for a business called “grok books…a good place to hang around” (239). Curious, I Googled “grok books” and learned it was founded in 1970 and later was sold and the name changed to Book People, which is still in business. Of course, The Rag, Liberation News Service and hundreds of underground papers were produced in the pre-computer, pre-internet, pre-Google era. Technology was a factor, nonetheless — for example, IBM Selectric and Executive typewriters and offset printing presses.

Also reproduced in the book are several letters to “the funnel,” as the editor was called (“funnella” when the editor was a woman). I will end this review with two of them:

From Norm Potter in San Francisco:

Funnel, I just found a copy of the Rag on my kitchen table one-half hour ago. It’s super-splendid. The art-work and layout are great, much better than the Psychodelphic Oracle here in S.F. (and that’s supposed to be a paper by and for hippies); like it’s not only pretty and well drawn, it’s highly imaginative, in good taste, and human. Maybe that’s what’s so good about your Rag; it’s human. I don’t feel that I’m reading about someone’s hollow posturing… (183)

And this one, unsigned: “You’re all a bunch of dirty, chicken, commie beatnik bastard queers and I bet you haven’t got the guts to print this” (192).

Allen Young

Allenyoung355@gmail.com

© 2017 Allen Young

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17541328.2017.1312091

[Allen Young was a reporter for the Washington Post but resigned in late 1967 to become a writer and editor at Liberation News Service (LNS) in New York. After the Stonewall Rebellion in 1969, Young became heavily involved in the Gay Liberation movement. He moved to rural Massachusetts, where he is an environmental activist and writes a weekly column at the Athol Daily News. Allen attended the 50th Rag Reunion and Celebration in October 2016 in Austin and has reviewed Celebrating The Rag for The Sixties: A Journal of History, Politics and Culture.]

Also see:

- “My Trip to the Rag Reunion” by Allen Young / The Rag Blog

- The Rag Book Page / The Rag Blog

- “Celebrating The Rag is a marvelous compendium that captures the paper’s unique spirit” by Thomas Zigal / The Rag Blog

Find Celebrating The Rag in Austin at BookPeople, BookWoman, Antone’s Records, and all Oat Willie’s and Planet K stores. Also in Houston at Brazos Bookstore, where there will be a presentation and booksigning Thursday, May 18, 2017, at 7 p.m. Get the book online at Lulu.com, Amazon.com, Barnes & Noble, and through Ingram.

Find Celebrating The Rag in Austin at BookPeople, BookWoman, Antone’s Records, and all Oat Willie’s and Planet K stores. Also in Houston at Brazos Bookstore, where there will be a presentation and booksigning Thursday, May 18, 2017, at 7 p.m. Get the book online at Lulu.com, Amazon.com, Barnes & Noble, and through Ingram.