Sex, Corruption and the Kool-Aid Massacre

By Paul Krassner / The Rag Blog / November 23, 2011

November 18th marked the 33rd anniversary of the Jonestown massacre.

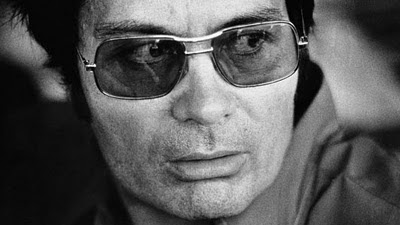

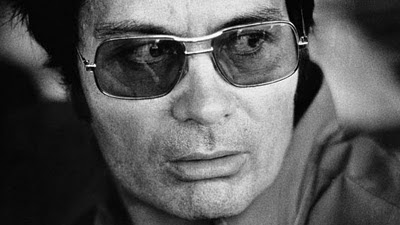

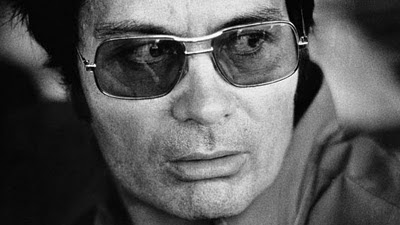

Jim Jones, founder of the 8,000-member People’s Temple in San Francisco, once asked Margo St. James, founder of the prostitutes’ rights group, COYOTE (Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics), how he could obtain political power.

She answered, sardonically, “Arrange for some of your women to have sex with the bigwigs.”

Jones in turn offered to supply busloads of his congregation for any protest demonstration that COYOTE organized, but Margo declined his offer.

“I never liked him,” she told me. “I never saw his eyes. Even in the dimmest light, he never removed his shades. He was hiding something. I figured it was his real feelings. I thought he was a slimy creep.”

Margo’s instincts were correct.

Potential recruits for People’s Temple were checked out in advance by Jones’ representatives, who would rummage through their garbage and report to him on their findings -– discarded letters, food preferences and other clues. Temple members would visit their homes, and while one would initiate conversation, the other would use the bathroom, copying names of doctors and types of medicine.

They would also phone relatives of a recruit in the guise of conducting a survey and gather other information that would all be taped to the inside of Jones’ podium, from which he would proceed to demonstrate his magical powers at a lecture by “sensing the presence” of an individual, mentioning specific details.

When People’s Temple moved to Guyana and became Jonestown, Jim Jones would publicly humiliate his followers. For example, he required them to remove their clothing and participate in boxing matches, pitting an elderly person against a young one. He forced one man to participate in a homosexual act in the presence of his girlfriend. There were paddle beatings and compulsory practice-suicide sessions called “White Nights.”

On November 18, 1978, Congressman Leo Ryan, who had been investigating Jonestown, was slain at the Guyana airport, along with three newspeople and several disillusioned members of the cult. Jones then orchestrated the mass suicide-murder of 900 men, women and children, mostly black.

Jones: “What’s going to happen here in a matter of a few minutes is that one of a few on that plane is gonna –- gonna shoot the pilot. I know that. I didn’t plan it, but I know it’s gonna happen. They’re gonna shoot that pilot and down comes the plane into the jungle. And we had better not have any of our children left when it’s over ’cause they’ll parachute in here on us. So my opinion is that we’d be kind to children and be kind to seniors and take over quietly, because we are not committing suicide. It’s a revolutionary act.”

Christine Miller: “I feel like that as long as there’s life, there’s hope. There’s hope. That’s my feeling.”

Jones: “Well, someday everybody dies. Someplace that hope runs out ’cause everybody dies.”

Miller: “But, uh, I look at all the babies and I think they deserve to live . . .”

Jones: “But also they deserve much more. They deserve peace.”

Unidentified man: “It’s over, sister, it’s over. We’ve made that day. We made a beautiful day. And let’s make it a beautiful day.”

Unidentified woman: [Sobbing] “We’re all ready to go. If you tell us we have to give our lives now, we’re ready . . .”

Jones: “The congressman has been murdered –- the congressman’s dead. Please get us some medication. It’s simple. It’s simple, there’s no convulsions with it, it’s just simple. Just please get it before it’s too late. The GDF [Guyanese army] will be here. I tell you, get moving, get moving, get moving. How many are dead? Aw, God almighty, God almighty — it’s too late, the congressman’s dead. The congressman’s aide’s dead. Many of our traitors are dead. They’re all layin’ out there dead.”

Nurse: “You have to move, and the people that are standing there in the aisle, go stay in the radio-room yard. So everybody get behind the table and back this way, okay? There’s nothing to worry about. So everybody keep calm, and try to keep your children calm. And the older children are to help lead the little children and reassure them. They aren’t crying from pain. It’s just a little bitter tasting, but that’s — they’re not crying out of any pain.”

Unidentified woman: “I just wanna say something to everyone that I see that is standing around and, uh, crying. This is nothing to cry about. This is something we could all rejoice about. We could be happy about this.”

Jones: “Please, for God’s sake, let’s get on with it. We’ve lived –- let’s just be done with it, let’s be done with the agony of it. [There is noise, confusion and applause.] Let’s get calm, let’s get calm. [There are screams in the background.] I don’t know who fired the shot, I don’t know who killed the congressman, but as far as I’m concerned, I killed him. You understand what I’m saying? I killed him. He had no business coming. I told him not to come. Die with respect. Die with a degree of dignity. Don’t lay down with tears and agony. Stop this hysterics. This is not the way for people who are socialistic communists to die. No way for us to die. We must die with some dignity.

“Children, it’s just something to put you to rest. Oh, God! [Crying in the background] I tell you, I don’t care how many screams you hear, I don’t care how many anguished cries, death is a million times preferable to ten more days of this life. It you’ll quit telling them they’re dying, if you adults will stop this nonsense -– I call on you to quit exciting your children when all they’re doing is going to a quiet rest. All they’re doing is taking a drink they take to go to sleep. That’s what death is, sleep. Take our life from us. We laid it down. We got tired. We didn’t commit suicide. We committed an act of revolutionary suicide, protesting the conditions of an inhuman world…”

Those who refused to drink the grape-flavored punch laced with potassium cyanide were either shot or killed by injections in their armpits. Jim Jones either shot himself or was murdered.

The Black Panther newspaper editorialized: “It is quite possible that the neutron bomb was used at Jonestown.”

* * *

When San Francisco District Attorney Joe Freitas learned of the killings, he was in Washington, D.C., conferring with the State Department about the mass suicide-murder in Jonestown. He immediately assumed that Moscone and Milk had been assassinated by a People’s Temple hit squad. After all, George Moscone was number one on their hit list.

Freitas had been a close friend of Jim Jones. After the massacre in Guyana, he released a previously “confidential” report, which stated that his office had uncovered evidence to support charges of homicide, child abduction, extortion, arson, battery, drug use, diversion of welfare funds, kidnapping, and sexual abuse against members of the sect. The purported investigation had not begun until after Jones left San Francisco. No charges were ever filed, and the People’s Temple case was put on “inactive status.”

Busloads of illegally registered People’s Temple members had voted in the 1975 San Francisco election, as well as in the runoff that put George Moscone in office. Freitas appointed lawyer Tim Stoen to look into possible voter fraud. At the time, Stoen was serving as Jim Jones’ chief legal adviser. Freitas later piously accused him of short-circuiting the investigation, but after Stoen left the case, the D.A.’s office assured the registrar that there was no need to retain the voting rosters, and they were destroyed.

Several former members of People’s Temple had heard about this fraudulent voting, but the eyewitnesses all died at Jonestown. In addition, the San Francisco Examiner reported that Mayor Moscone had called off a police investigation of gun-running by the Temple, which had arranged to ship explosives, weapons, and large amounts of cash to South America via Canada.

George Moscone’s body was buried. Harvey Milk’s body was cremated. His ashes were placed in a box, which was wrapped in Doonesbury comic strips, then scattered at sea. The ashes had been mixed with the contents of two packets of grape Kool-Aid, forming a purple patch on the Pacific. Harvey would’ve liked that touch.

* * *

It was well known around City Hall that Moscone had a predilection for black women. Police almost arrested him once with a black prostitute in a car at a supermarket parking lot.

Soon after the Dan White trial, I got a phone call from Lee Cole, an ex-Scientologist I had met in Chicago while researching the Charles Manson case. He wanted to visit me, but I said no.

“Suppose I just come over?” he said.

“You don’t know where I live.”

“I can find out.”

“If you find out, and you tell me how you did it, you can come over.”

I wanted to determine how carefully I had covered my tracks, or see which friend would give out my address. A little while later, Lee Cole called again and told me my address — he said that he had obtained it from the voter registration files — so I told him to come over.

He took me to see Lowell Streiker, author of The Cults Are Coming! and a deprogrammer who had counseled one-third of the Jonestown survivors. In the course of our conversation, I mentioned my theory that Jim Jones had served as a pimp at City Hall and maintained power by implied blackmail.

Dr. Streiker told me of his friend — a member of Jones’ planning commission — who had told him about the technique that People’s Temple had used on Mayor Moscone. They sent a young black female member to service him, as a gift, then called the next week about a serious problem — she had lied, said she was 18, when in fact she was underage, but don’t worry, we have it under control — just the way J. Edgar Hoover used to manipulate top politicians with his juicy FBI files.

So Jim Jones had taken Margo St. James’ sardonic advice after all, on how to achieve political power: “Arrange for some of your women to have sex with the bigwigs.” And he had taken it all the way to a mass suicide-murder — which occurred simultaneously with a mass demonstration by the women’s movement in San Francisco, called “Take Back the Night!”

They completely shut down traffic on Broadway. But there was not a word about that event in any of the media. It was knocked totally out of the news by the massacre in Jonestown.

Jonestown and Kool-Aid continue to serve as occasional joke references for stand-up comedians and metaphors for politicians and pundits alike.

[Paul Krassner edited The Realist, America’s premier satirical rag. He was also a founder of the Yippies. Find Paul’s autobiography, Confessions of a Raving Unconfined Nut: Misadventures in the Counterculture at paulkrassner.com. Paul Krassner’s dialogue with Andrew Breitbart appears in the December issue of Playboy. Read more articles by Paul Krassner on The Rag Blog.]

Source /

The Rag Blog