Nature bats last:

Notes on revolution and resistance,

revelation and redemption

By Robert Jensen / The Rag Blog / August 14, 2011

[An edited version of this essay was presented as a talk to the Veterans for Peace conference in Portland, Oregon, on August 4, 2011.]

My title is ambitious and ambiguous: revolution and resistance (which tend to be associated with left politics), revelation and redemption (typically associated with right-wing religion), all framed by a warning about ecological collapse. My goal is to connect these concepts to support an argument for a radical political theology — let me add to the ambiguity here — that can help us claim our power at the moment when we are more powerless than ever, and identify the sources of hope when there is no hope.

First, I realize that the term “radical political theology” may be annoying. Some people will dislike “radical” and prefer a more pragmatic approach. Others will argue that theology shouldn’t be political. Still others will want nothing to do with theology of any kind. At various times in my life, I would have offered all of those objections. Today, I think a politics without a theology is dangerous, a theology without a politics is irrelevant, and radical is realistic.

By politics, I don’t mean we need to pretend to have worked out a traditional political program that will lead us to the land of milk and honey; instead, I’m merely suggesting that we always foreground the basic struggle for power in whatever work we do at whatever level. By theology, I don’t mean that we need to believe in supernatural forces that will lead us to a land of milk and honey; instead, I’m merely pointing out that we all construct a worldview that is not reducible to evidence and logic.

In politics and theology, it’s important to be clear about what we know, and even more important to recognize what we don’t know, what we can’t know, what is instinct and emotion.

And all this needs to be radical — not in the self-indulgent “more radical than thou” style that crops up now and then on the left — but rather in the sense of an unflinching honesty about that unjust and unsustainable nature of the systems in which we live. Whatever pragmatic steps we may decide to take in the world, they should be based on radical analysis if they are to be realistic.

Revolution

I’m not interested in speculating about future revolutions, I don’t take seriously anyone who predicts a coming revolution in the United States, and I doubt that the traditional concept of a revolution is even relevant today — the dramatic changes that lie ahead likely won’t arrive that way. Rather than dream of revolutions to come, it’s more productive to think about the revolutions that brought us to this moment.

Ask an audience to name the three most important revolutions in human history, and the most common answers are the American, French, and Russian. But to understand our current situation, the better answer is the agricultural, industrial, and delusional revolutions. While those national revolutions had dramatic effects, not only on those nations but on the course of the history of the past two centuries, these other revolutions not only reshaped the lives of every human but remade the world in ways that may spell the end of human history as we know it. The agricultural, industrial, and delusional revolutions were — to use a current political cliché — real game-changers.

The agricultural revolution started about 10,000 years ago when a gathering-hunting species discovered how to cultivate plants for food and domesticate animals. Two crucial things resulted, one political and one ecological. Politically, the ability to stockpile food made possible concentrations of power and resulting hierarchies that were foreign to band-level gathering-hunting societies, which were highly egalitarian and based on cooperation.

This is not to say that humans were not capable of doing bad things to each other prior to agriculture, but only that large-scale institutionalized oppression has its roots in agriculture. We need not romanticize pre-agricultural life but simply recognize that it was organized in far more egalitarian fashion than what we call “civilization.”

Ecologically, the invention of agriculture kicked off an intensive human assault on natural systems. While gathering-hunting humans were capable of damaging a local ecosystem in limited ways, the large-scale destruction we cope with today has its origins in agriculture, in the way humans started exhausting the energy-rich carbon of the planet, first in soil.

Human agricultural practices have varied over time and place but have never been sustainable over the long term. There are better and worse farming practices, but soil erosion has been a consistent feature of agriculture, which makes it the first step in the entrenchment of an unsustainable human economy based on extraction.

We are trained to think that advances in technology constitute progress, but the post-World War II “advances” in oil-based industrial agriculture have accelerated the ecological destruction. Soil from large monoculture fields drenched in petrochemicals not only continues to erode but also threatens groundwater supplies and contributes to dead zones in oceans.

While it’s true that this industrial agriculture has produced tremendous yield increases during the last century, no one has come up with a sustainable system for perpetuating that kind of agricultural productivity. Those high yields mask what Wes Jackson has called “the failure of success”: Production remains high while the health of the soil continues to decline dramatically.[1]

That kind of “success” guarantees the inevitable collapse of the system. We have less soil that is more degraded, with no technological substitute for healthy soil; we are exhausting and contaminating groundwater; and we are dependent on an agriculture tied to a fuel source that is running out.

That industrialization of agriculture was made possible, of course, by the larger industrial revolution that began in the last half of the 18th century in Great Britain, which intensified the magnitude of the human assault on ecosystems and humans assaults on each other.

This revolution unleashed the concentrated energy of coal, oil, and natural gas to run the new steam engine and machines in textile manufacturing that dramatically increased productivity. That energy — harnessed by the predatory capitalist economic system that was beginning to dominate the planet — not only eventually transformed all manufacturing, transportation, and communication, but disrupted social relations.

People were pushed off the land, out of communities, and into cities that grew rapidly, often without planning. Traditional ways of knowing and living were destroyed, by force or by the allure of affluence. World population soared from about 1 billion in 1800 to the current 7 billion, far beyond the long-term carrying capacity of the planet.

This move from a sun-powered and muscle-based world to a fossil fuel-powered and machine-based world has produced unparalleled material comfort for some. Whatever one thinks of the effect of such levels of comfort on human well-being — in my view, the effect has been mixed at best[2] — the processes that produce the comfort are destroying the capacity of the ecosystem to sustain human life as we know it into the future, and in the present those comforts are not distributed in a fashion that is consistent with any meaningful conception of justice.

In short, our world is unsustainable and unjust — the way we live is in direct conflict with common sense and the ethical principles on which we claim to base our lives. How is that possible? Enter the third revolution.

The delusional revolution is my term for the development of sophisticated propaganda techniques in the 20th century (especially a highly emotive, image-based advertising/marketing system) that have produced in the bulk of the population (especially in First World societies) a distinctly delusional state of being.

Although any person or group can employ these techniques, wealthy individuals and corporations — and their representatives in government — take advantage of their disproportionate share of resources to flood the culture with their stories that reinforce their dominance. Journalism and education, idealized as spaces for rationally based truth-telling, sometimes provide a counter to those propaganda systems, but just as often are co-opted by the powerful forces behind them.

Perhaps the most stunning example of this is that during the 2000s, as the evidence for human-caused climate disruption became more compelling, the percentage of the population that rejects that science increased.

Why would people who, in most every other aspect of life accept without question the results of peer-reviewed science, reject the overwhelming consensus of climate scientists in this case? Some have theological reasons, and for others perhaps it is simply easier to disbelieve than to face the implications. But it’s clear that the well-funded media campaigns using these propaganda techniques to create doubt have been effective.[3]

Even those of us who try to resist it often can’t help but be drawn into parts of the delusion; it’s difficult to keep track of, let alone understand, all of the fronts on which we are facing serious challenges to a just and sustainable future.

As a culture, these delusions leave us acting as if unsustainable systems can be sustained simply because we want them to be. Much of the culture’s story-telling — particularly that which comes through almost all of the mass media — remains committed to maintaining this delusional state. In such a culture, it becomes hard to extract oneself from that story.

Singer/songwriter Greg Brown captures the trajectory of this delusional revolution when he speculates that one day, “There’ll be one corporation selling one little box/it’ll do what you want and tell you what you want and cost whatever you got.”[4]

In summary: The agricultural revolution set us on a road to destruction. The industrial revolution ramped up our speed. The delusional revolution has prevented us from coming to terms with the reality of where we are and where we are heading.

Resistance

Even if a revolutionary program is not viable at the moment, strategies and tactics for resistance are crucial. To acknowledge that the social, economic, and political systems that have produced this death spiral can’t be overthrown from the revolutionary playbooks of the past does not mean there are no ways to affirm life.

We face planetary problems that seem to defy solutions, but the U.S. empire and predatory corporate capitalism remain immediate threats and should be resisted. An honest, radical assessment of our situation doesn’t mean giving up, but it requires us to be tough-minded. We need to understand which resistance strategies and tactics are likely to be most productive at this moment in history.

To advance that discussion, let’s think back to February 15, 2003. Many of us on that Saturday participated in actions in opposition to the planned U.S. invasion of Iraq. It was an exhilarating day, the largest coordinated political protest in the history of the world.

At least 10 million people participated across the globe, with a clear message for U.S. policymakers: The invasion being planned is illegal and immoral, and we reject not only this war but your right to use violence to achieve your political and economic goals. I was the emcee of the event in Austin, and I remember being amazed at the thousands who gathered at the Texas Capitol, stretching back so far that our loudspeakers couldn’t reach the entire crowd.

We had a compelling message, rooted in international law, political principles, and moral values. We had huge numbers of people. We had an international presence. And none of it mattered; the war came.

Why could U.S. policymakers ignore us without consequence? First, those elites knew that a large segment of the public either actively supported the war or would passively support almost any war that was out of sight/out of mind. Second, they knew that when that day of protest was over, most of the people in the streets would go home, satisfied with their public statement and unlikely to go beyond that polite expression of dissent.

Political movements are most potent when people are willing to take risks; without a large number of such people, the powerful know they can wait out protests.

For most people, attending an anti-war rally posed no risk. Immigrants and people in targeted groups (Arabs, South Asians, Muslims) had reason to feel threatened, but people who look like me — with only rare exceptions — don’t face serious repression in the United States today for engaging in peaceful political activity, though that can change quickly.

What were most of us willing to do beyond attending a rally in opposition to a war being planned? A month later, when the war came, we got a partial answer. The crowd for the standing call to come to the Capitol when the bombs fell was at best one-fourth of the pre-war rally. Most of the people who came on February 15 weren’t willing to come out in public once the nation was at war; even that trivial a risk was too much.

I could be cocky and say that in 2003 I was willing to risk my job, my physical safety, even my life to stop the war. It might be true; I certainly felt the urgency of the moment. But the question is moot, because at that time there was no strategy for taking such risks. These decisions about risk are made by individuals but in the context of options developed collectively, and the movement I was part of had not discussed such options.

So, when certain resistance tactics don’t work as part of a strategy that’s not clearly articulated, it’s time to rethink. I have no grand strategy to offer, and I am skeptical about anyone who claims they have worked out such a strategy. But I am reasonably confident that this is not a mass-movement moment, not a time in which large numbers of Americans are likely to engage in political activity that challenges basic systems of power and wealth.

I believe we are in a period in which the most important work is creating the organizations and networks that will be important in the future, when the political conditions change, for better or worse. Whatever is coming, we need sharper analysis, stronger vehicles for action, and more resilient connections among people. In short, this is a cadre-building moment.

Although for some people the phrase “cadre-building” may invoke the worst of the left’s revolutionary dogmatism, I have something different in mind. For me, “cadre” doesn’t mean “vanguard” or “self-appointed bearers of truth.” It signals commitment, but with an openness to rethinking theory and practice.

I see this kind of organizing in some groups in Austin, TX, where I live. Not surprisingly, they are groups led by younger people who are drawing on longstanding radical ideas, updating as needed to fit a changing world. These organizers don’t have all the answers, and I don’t agree with some of the answers they do have, but I am drawn to them because they recognize the need to dig in.

Revelation

Most discussions of revelation and apocalypse in contemporary America focus on the Book of Revelation, also known as The Apocalypse of John, the final book of the Christian New Testament. The two terms are synonymous in their original meaning — “revelation” from Latin and “apocalypse” from Greek both mean a lifting of the veil, a disclosure of something hidden from most people, a coming to clarity. What is the nature of this unveiling today? What is being revealed to us?

A reactionary end-times theology turns that particular book of the Bible into the handbook for a death cult, fantasizing about an easy way out. That isn’t the direction I will be heading. Rather than thinking of revelation as divine delivery of a clear message about some fantastic future above, we can think of it as a process that requires tremendous effort on our part about our very real struggles on this planet.

That notion of revelation doesn’t offer a one-way ticket to a better place, but reminds us that there are no tickets available to any other place; we humans live and die on this planet, and we have a lot of work to do if, as a species, we want to keep living.

That process begins with an honest analysis of where we stand. There is a growing realization that we have disrupted natural forces in ways we cannot control and do not fully understand. We need not adopt an end-times theology to recognize that on our current trajectory, there will come a point when the ecosphere cannot sustain human life as we know it.

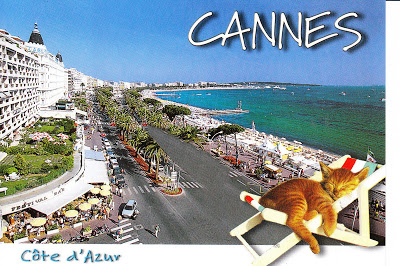

As Bill McKibben puts it, “The world hasn’t ended, but the world as we know it has — even if we don’t quite know it yet.”[5]

McKibben, the first popular writer to alert the world to the threat of climate change, argues that humans have so dramatically changed the planet’s ecosystems that we should rename the Earth, call it Eaarth:

The planet on which our civilization evolved no longer exists. The stability that produced that civilization has vanished; epic changes have begun. We may, with commitment and luck, yet be able to maintain a planet that will sustain some kind of civilization, but it won’t be the same planet, and hence it won’t be the same civilization. The earth that we knew — the only earth that we ever knew — is gone.[6]

If McKibben is accurate — and I think the evidence clearly supports his assessment — then we can’t pretend all that’s needed is tinkering with existing systems to fix a few environmental problems; massive changes in how we live are required, what McKibben characterizes as a new kind of civilization.

No matter where any one of us sits in the social and economic hierarchies, there is no escape from the dislocations of such changes. Money and power might insulate some from the most wrenching consequences of these shifts, but there is no escape. We do not live in stable societies and no longer live on a stable planet. We may feel safe and secure in specific places at specific times, but it’s hard to believe in any safety and security in a collective sense.

This is a revelation not of a coming rapture but of a deepening rupture. The end times are not coming, they are unfolding now.

Redemption

Just as revelation can be about more than explosions during the end times, redemption can be understood as about more than a savior’s blood washing away our sin. In a world in which so many decent people have been psychologically and theologically abused by being called “sinner” by jealous and judgmental scolds, sin and redemption are tricky terms.

But we shouldn’t give up on the concept of sin, for we are in fact all sinners — we all do things that fall short of the principles on which we claim to base our lives. Everyone I know has at some point lied to avoid accountability, failed to offer help to someone in need, taken more than their fair share.

Given that we all sin, we all should seek redemption, understood as the struggle to come back into right relation with those we have injured. If we are to live up to our own moral standards, we must deepen our understanding of sin and its causes so that we can understand the path to redemption.

For Christians, sin traditionally has been marked as original and individual — we are born with it, and we can deal with it through an individual profession of faith. In some sense, of course, sin is obviously original. At some point in our lives we all do things that violate our own principles, which suggests the capacity to do nasty things is a part of normal human psychology.

Equally obvious is that even though we live interdependently and our actions are conditioned by how we are socialized, we are distinct moral agents and we make choices. Responsibility for those choices must in part be ours as individuals.

But an individual focus isn’t going to solve our most pressing problems, which is why it is crucial to focus on the sins we commit that are created, not original, and solutions that are collective, not individual.

These sins, which do much greater damage, are the result of — we might say, created by — political, economic, and social systems. Those systems create war and poverty, discrimination and oppression, not simply through the freely chosen actions of individuals but because of the nature of these systems of empire and capitalism, rooted in white supremacy and patriarchy. Humans’ ordinary capacity to sin is intensified, reaching a different order of magnitude, and responsibility for the resulting sins is shared.

There is a politics to sin, and therefore there has to be a politics to redemption. That desire to return to right relation with others in our personal lives is not enough; collectively we have to struggle for the same thing, which requires us to always be working to dismantle those hierarchical systems that define our lives.

Within hierarchy, right relation is impossible; assertions of dominance and concentrations of power create domination and abuses of power. That includes the most abusive of all hierarchies: The human claim to a right to dominate everything else. Our most important struggle for redemption concerns our most profound sin: Our willingness to destroy the larger living world of which we are a part.

The first step in redemption is to not turn away from that lifting of the veil, to face honestly what we have done, to contest the culture’s delusions wherever possible. Then we can face what we must do to enhance justice and build sustainable living arrangements.

What does this kind of redemption look like in practice? I think we should proceed along two basic tracks. First, we should commit some of our energy to the familiar movements that focus on the question of justice in this world, such as anti-war struggles. We redeem ourselves — especially those of us with privilege that is rooted in that injustice — through that commitment to fighting empire, capitalism, white supremacy, and patriarchy.

But I also think there is important work to be done in experiments to prepare for what will come in this new future we can’t yet describe in detail. Whatever the limits of our predictive capacity, we can be pretty sure we will need ways of organizing ourselves to help us live in a world with less energy and fewer material goods.

We have to all develop the skills needed for that world (such as gardening with fewer inputs, food preparation and storage, and basic tinkering), and we will need to recover a deep sense of community that has disappeared from many of our lives. McKibben puts this in terms of a new scale for our work:

The project we’re now undertaking — maintenance, graceful decline, hunkering down, holding on against the storm — requires a different scale. Instead of continents and vast nations, we need to think about states, about town, about neighborhoods, about blocks… We need to scale back, to go to ground. We need to take what wealth we have left and figure out how we’re going to use it, not to spin the wheel one more time but to slow the wheel down… We need, as it were, to trade in the big house for something that suits our circumstances on this new Eaarth. We need to feel our vulnerability.”[7]

Nature bats last

The phrase “nature bats last” circulates these days among people who have their eye on the multiple, cascading ecological crises. The metaphor reminds us that nature is the home team and has the final word. We humans may be particularly impressed with our own achievements — all of the spectacular home runs we have hit with science and technology — but when those achievements are at odds with how nature operates, then nature is going to bring in the ultimate designated hitter and knock the human race out of the ballpark.

OK, let’s not try to stretch this too far — no single metaphor can work at every level needed. The point is simple: We are not as powerful as the forces that govern that larger living world.

The metaphor offers one other crucial lesson, in this case because of its limitations. When we say “nature bats last,” it implies we are one team and nature is on another, as if it were possible for us to compete with nature. But we are, of course, simply part of nature, one species in an indescribably diverse living world. To imagine ourselves as competing with nature would be like our lungs competing with our heart — either those organs work together, or an individual human dies.

Unfortunately, the architects of modern science didn’t see the world that way. One of the most often-quoted, Francis Bacon, believed that modern science and technology “have the power to conquer and subdue [nature], to shake her to her foundations.” Rene Descartes, another of these founding fathers, believed humans could achieve the knowledge and develop the means to know:

the force and action of fire, water, air, the stars, the heavens, and all the other bodies that surround us, as distinctly as we know the various crafts of our artisans, we might also apply them in the same way to all the uses to which they are adapted, and thus render ourselves the lords and possessors of nature.

These thinkers also contributed to our understanding of the workings and power of the natural world. But this language of domination — to conquer and subdue, becoming lords and possessors — is the language not of a baseball game but of war, which brings us to the relevance of this to Veterans for Peace. VFP members have seen through and gone beyond the egotistical rhetoric of our national fundamentalism — with all its fraudulent claims about “fighting for freedom” — to reject the U.S. wars of empire and stake out an audacious goal: “To abolish war as an instrument of national policy.”

We also need to see beyond the egotistical rhetoric of our technological fundamentalism — the claims that infinitely clever humans will solve all problems with gadgets — and stake out an even more audacious goal: To end the human war on the rest of living world.

Life is hard

If all this seems too much to ask of ourselves, that’s because it is. We live in a time when we must face honestly the whole truth, but to do that is too much to bear. We struggle to claim our power at the moment when we are more powerless than ever, and find hope where there is no hope.

On power: Those of us in dissident movements understand we face difficult odds, fighting entrenched forces of the state and corporation. We know the keys to prevailing: Fight organized money with organized people; compromise to build a power base but never abandon core principles; find ways to delegitimize authority; raise the social costs for elites to pursue unjust policies; hang in for the long haul. Those organizing basics don’t change, though the application of them must constantly adapt to changes in the structure of power. But the ecological crises change things in the big picture.

First, we should not assume the long haul is as long as we’ve always imagined. No one can predict the rate of collapse if we stay on this trajectory, and we don’t know if we can change the trajectory.

There is much we don’t know, but everything I see suggests that the world in which we will pursue political goals will change dramatically in the next decade or two, almost certainly for the worse. Organizing has to adapt not only to changes in societies but to these fundamental changes in the ecosphere. We are organizing in a period of contraction, not expansion.

Second, we can’t be satisfied with contesting imperialism in the nation-state and the concentration of wealth in corporate capitalism, but also must change the human relationship to the living world.

Dissident movements have an advantage, given that a larger percentage of people involved in left/radical politics have less of a commitment to maintaining the dominant culture’s delusions. Radicals don’t have the wealth and power that can appear to insulate us from collapse, which means we have more room to think about what living arrangements are consistent with reality. Elites, who typically mistake temporary domination for real power, have a harder time recognizing that humans are powerless in the face of the forces we have been trying to conquer and subdue.

In the end, we can never be the lords and possessors of something larger and more enduring in time. Many traditions recognize this basic reality: We don’t own the earth, the earth owns us. Our power comes in recognizing our powerlessness and adapting to the world as it is, not the world as we imagine it to be.

How does this approach give people hope? It doesn’t, and it shouldn’t, because hope is not something you give to people. The political organizers on the liberal/left who are always touting a new way to restore the American Dream are peddlers of false hope, offering allegedly exciting opportunities to allegedly new movements that are stuck in the same old failed ideology of the dominant culture, steadfastly ignoring the depth and scope of the ecological crises.

Real hope comes with abandoning the false prophets and moving on to accomplish something. Authentic hope comes when we honestly confront our condition and dig in to create new, or revive old, forms of community. Hope comes from proving to ourselves that we are competent to manage our own lives. Hope doesn’t fall from the sky but rather is built from the ground up.

That hope doesn’t ask for guarantees that our movements will prevail. That hope doesn’t require us to pretend we know whether the human experiment will go on forever. That hope comes from the understanding that while we did not choose to live in a desecrated world, such is the world into which we were born.

All we can do is act out of respect for ourselves, for each other, and for nature, in the hope that we can restore the sacredness of the individual, the human community in which individuals find meaning, and the living world of which human communities are a part.

Organizers have long said that the key to successful organizing is making it easy for people to do the right thing. Today, our task is to be honest about how difficult it is to do the right thing. Anyone who thinks it can be easy to do the right thing is part of the delusional culture. Rather than delude ourselves, let’s face the truth and recognize the difficulty of the path that lies ahead.

Other social movements have prevailed in the face of great difficulty, but no social movement has had to face this simple but profound reality: We have to become the first species on the planet to practice restraint in the scramble for energy-rich carbon. All life on this planet is based on that scramble, but if we continue on the path unchecked the planet will be incapable of sustaining human life as we know it.

That is a brand new organizing challenge. In facing it, we need to leave the platitudes at home.

The radical political theology I believe we need for this moment in history would acknowledge, rather than try to mask, our confusion and uncertainty. We know we are in deep trouble; beyond that, it’s guesswork. Facing that takes a new kind of courage.

We usually think of courage as rooted in clarity and certainty — we act with courage when we are sure of what we know. Today, the courage we need must be rooted in the limits of what we can know and trust in something beyond human knowledge. In many times and places, that something has gone by the name “God.”

Religious fundamentalism offers a God who will protect us if we follow orders. Technological fundamentalism gives us the illusion that we are God and can arrange the world as we like it. A radical political theology leaves behind fear-based protection rackets and arrogance-driven control fantasies.

The God for our journey is neither above us nor inside us but around us, a reminder of the sacredness of the living world of which we are a part. That God shares the anxiety and anguish of life in a desecrated world. With such a God we can be at peace with our powerlessness and alive in hope. With such a God, we can live in peace.

References:

[1] Wes Jackson, New Roots for Agriculture (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1980), chapter 2. Many of my points in this talk were greatly influence by the work of Jackson and The Land Institute, http://www.landinstitute.org.

[2] Tim Kasser, The High Price of Materialism (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002).

[3] Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway, Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2010).

[4] Greg Brown, “Where Is Maria?” from the CD “Further In,” Red House Records, 1996.

[5] Bill McKibben, Eaarth: Making Life on a Tough New Planet (New York: Times Books/Henry Holt, 2010), p. 2.

[6] McKibben, Eaarth, p. 25.

[7] McKibben, Eaarth, p. 123.

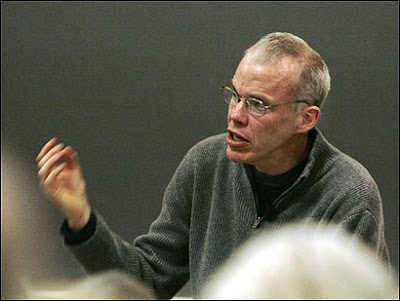

[Robert Jensen is a journalism professor at the University of Texas at Austin, where he teaches courses in media law, ethics, and politics — and a board member of the Third Coast Activist Resource Center in Austin. His books include All My Bones Shake: Seeking a Progressive Path to the Prophetic Voice, and Getting Off: Pornography and the End of Masculinity. His writing is published extensively in mainstream and alternative media. Robert Jensen can be reached at rjensen@uts.cc.utexas.edu. Read more articles by Robert Jensen on The Rag Blog.]