Thorne Webb Dreyer, Editor

SEARCH

RECENT POSTS

CARL DAVIDSON / POLITICS / SUMMING UP THE YEAR 2025

January 16, 2026

BRUCE MELTON / CLIMATE CHANGE / Climate Change Review 2025

December 31, 2025

JONAH RASKIN / BOOK REVIEW / Levitating the Pentagon

December 29, 2025

LARRY PILTZ / VERSE / Save The Futures

December 10, 2025

ALLEN YOUNG / BOOK REVIEW / The Trees are Speaking

December 3, 2025

ALICE EMBREE / MEDIA / A new Rag for a new generation

November 6, 2025

ARCHIVES

Posted in RagBlog

Leave a comment

INTERVIEW / Jonah Raskin : The Quest of Cannabis King Jorge Cervantes

|

| Jorge Cervantes with some of his queenly Cannabis plants. Photos special to The Rag Blog. |

An Interview with Jorge Cervantes:

The king of marijuana cultivators and

his quest for the ‘Queens of Cannabis’

Marijuana will keep its underground character for a while, but it will eventually become legal. The wind is blowing in that direction. Politicians like to be on the winning side and cannabis is slowly winning.

By Jonah Raskin | The Rag Blog | August 27, 2013

Call him the counterculture godfather of cannabis cultivation. He’s the go-to guy who can tell you — in nearly every media, new and old — when to plant a crop, when to harvest it and what to do in-between. His YouTube channel — has had nearly 5 million hits since it started in 2010.

Or, better yet, just call him Mr. God. He’s the author of the best-selling bible on both indoor and outdoor marijuana cultivation first published in 1983, and with hundreds of thousands of copies in print. Unlike God, who rested on the seventh day, Jorge Cervantes hardly takes a day off. Over the last five years he’s worked — with time out for a joint or two — on a new book that offers nearly all the cannabis information you could want. Out January 2014, it’s entitled Marijuana Horticulture: The Indoor/Outdoor Medical Grower’s Bible and it’s a labor of love.

An editor, publisher, photographer, researcher, and the writer of all his books, Jorge Cervantes, 59 years old, was born George Van Patten in Ontario, Oregon, near the Idaho border. (His alias is hardy a secret. Jorge is George in Spanish. Miguel Cervantes, the author of Don Quixote, is his favorite writer.)

George smoked his first joint — rolled from “dirt weed,” he says — in 1968, when Mexican pounds sold for $100. Not long afterwards, George morphed into Jorge. Ever since then, his journey has taken him to California and to Spain, where he lives much of the year, writing, making videos, and appearing at cannabis fairs where he’s become an iconic figure, nearly as recognizable as Don Quixote himself.

Jorge Cervantes wasn’t the first cannabis aficionado to write how-to-books for cultivators. Mel Frank and Ed Rosenthal preceded him. Their Marijuana Grower’s Guide, first published in 1980, became perhaps the most popular how-to-grow-sinsemilla book during the Reagan era War on Drugs.

Cervantes quickly caught up — and along the way never got arrested. No one in the global cannabis world is more visible than he, and yet no icon in the cannabis world is more invisible. Like Frank and Rosenthal, he’s been a long-time High Times columnist and as devoted a HT reader as anyone around.

“He’s tenacious,” HT editor Chris Simunek says. “He’s a real horticulturist who loves all kinds of plants.” Cervantes began the interview by speaking in Spanish, then changed to English. He’s fluent in both languages.

Jonah Raskin: What’s it like there now in Barcelona?

Jorge Cervantes: It’s raining buckets of water and as they say, rain makes the flowers grow.

In Spain is there a shift from hash to cannabis?

It took a long time before cannabis became popular in Spain. We‘re across the Straits of Gibraltar and Moroccan hash is relatively inexpensive and abundant here. Domestically grown cannabis has come down in price; it’s nearly the same as hash. Now, in Spain, people are cultivating cannabis for less money than it takes to buy hash. There’s also so much cannabis here that people are making hash and concentrated oils.

In my part of California, growers are “sitting on” their medicine. What’s the supply/demand story in your world?

Unemployment in Spain is 27%. The number is double for those under 30. Growing cannabis is a way to survive. Few Spanish growers have the luxury of holding out for a higher price. Moreover, the 27 countries in the European Union provide a large market. The price of cannabis will remain less volatile than in the U.S where growers produce much more than can be consumed and where oversupply drives down the price. In Europe, the cost of production and transportation have remained surprisingly stable.

In what ways have the Spanish learned from U.S. farmers?

Spanish growers have taken information from the best cannabis cultivators in the world. They’re adapting it to their conditions. Then, too, over the last 20 years, growers from all over Europe, especially the Netherlands, have moved to Spain. American and Canadian cannabis companies have a major presence through huge trade fairs (www.cannabis.com, www.growmed.es, www.expocannabis.com, and www.expogrow.net). They’re the biggest in the world.

Some guerrilla growers in the States go into forests and damage the environment. What’s the Spanish awareness about the environment?

Until Spain entered the EU, their track record on environmental responsibility was low. Today attitude has improved. Guerilla growers tend to be messy, but most of them remove trash because it attracts unwanted attention.

Are growers growing organically? Do companies make soil mixes and “teas”?

Organic gardening is around but it is not as developed as it is in the U.S or Germany. There’s a basic knowledge about composting and growers use compost teas. But, I have not seen activated aerated compost teas (AACT) in use. The U.S. is more innovative in this respect, but the technology is moving to Spain. I recently gave two lectures at GrowMed in Valencia where I talked about AACT. Growers want to try it.

Has greed crept into the cannabis culture in Spain? Have Spaniards becoming wealthy, as has happened in California?

When money is involved there’s bound to be greed. But greed and getting rich don’t drive the bulk of Spanish growers. Most start off wanting to grow their own cannabis so that they don’t have to buy it. Some overproduce. When they do, they give to friends or make hash for personal consumption.

What about cannabis clubs?

They started to surface a few years ago. Their location is not advertised and they’re behind secure doors. Members are charged a modest annual fee. When they belong they can purchase small amounts of cannabis. But the legality of the clubs is up in the air and so the situation is unstable.

Spain has come a long way since the days of the dictator, Franco, hasn’t it?

The funny thing about Spain under Franco is that hashish was a common commodity. Many soldiers and fishermen, too, smoked it. Smuggling hash into the country was commonplace. I smoked it in Spain when Franco was still alive. In fact, the military controlled many of the hash smuggling operations.

In the 1980s, I remember people smoking joints in Spanish resort towns. During the 1990s, when there were squats around Barcelona, everybody smoked Moroccan hash. Today, the biggest cannabis fairs in the world are in Spain. Spannabis in Barcelona is by far the biggest of all. Spain is a natural for cannabis: sunny, relatively inexpensive and tolerated when cultivation is on a small scale.

So, the police are not a heavy presence?

In Spain there is a big respect for personal space and individual sovereignty. The police don’t have the same kinds of power in Spain they do in the States. They’re not real heavy or overbearing. They would not, for example, stop someone and search a backpack.

Why do you think the DEA is so against cannabis?

I think they want to keep their jobs and get paid. They also really believe it’s bad for you.

Are doctors recommending or prescribing cannabis?

Spain legalized medical cannabis in 2006. The province of Cataluña — where I live — also legalized distribution through pharmacies, but the current financial crisis has prevented the creation of a distribution network.

At the recent GrowMed Fair in Valencia, several doctors talked about the medical benefits. They prescribe it for many ailments. Several medical studies have been completed in Spain, including Dr. Guzman’s 2000 “Pot Shrinks Tumors,” and there’s an organization, Fundación CANNA, that studies the medical properties of cannabis.

Are there regions where there’s more of it grown? Are there urban gardens?

More cannabis is grown in the Basque country, Cataluña, and on the Mediterranean Coast than in the interior. But other regions are growing their fair share of cannabis, so much so that cannabis theft is a problem. Outdoor cultivation is bigger than indoor cultivation. Greenhouse cultivation is also popular. In Galicia, where it rains more in than in Seattle, growing outdoors is difficult. Growing in a greenhouse works well there and hydroponic stores have opened.

The magazine, Soft Secrets, published in seven languages, is the biggest in Europe and is widely read by indoor and outdoor growers. All editions, except for the Spanish one, show a country flag on top of the front page. Spain is a group of distinct zones. We speak five different languages: Gallego, Basco, Catalan, Asturiano, and Castellano (Spanish) and every region differs geographically, climatically, and culturally.

If you walk around Barcelona in the summertime, cannabis growing on balconies is a relatively common sight. Indoor urban gardens are also commonplace. They’re generally small because of the limited space and electrical service.

In California, there are neighborhoods where you smell cannabis at harvest because there’s so much of it. Is it similar in Spain?

Yes! It’s a problem! But a bigger one is rogue male pollen in the air. Many people grow from seed here and male plants are common. I have attended neighborhood meetings where residents bring photos of male plants and ask neighbors to pull them. Fragrance is a problem only with large stands of cannabis outdoors, which is not common.

What is the legal status of cannabis in Spain?

It’s legal to grow for personal consumption and it isn’t a crime to consume cannabis. But the legal situation is still unclear because the law is interpreted differently and enforced inconsistently. Of course, it’s illegal to sell cannabis, but the clubs are all doing it. In the Basque and Cataluña, laws appear to be more lax.

Are there “stoners” In Spain?

In Spain there never was a “stoner hippie” stereotype. But in Spanish there’s lots of cannabis slang. A stoner might be a “fumeta” in Spain or a “voludo” in Latin America, but those words are more common in South America. Spanish is a very rich language that lends itself to innovation. However, unlike English, cannabis terms evolve around describing an object or the effect of a substance.

Spain has a long history of hashish smoking so there’s a rich vocabulary to describe hash. “China’ is the word for a small piece of hash, “pedazo” the word for a larger piece of hash, and “taco” for a still larger piece of hash.

I like the notion that we ought not to separate and distinguish between the “recreational” user and the “medicinal” user. What thought do you have about that?

I believe that recreational users can be classified as medicinal users. Consuming cannabis lowers pressure in the body. It’s relaxing and therapeutic.

How is the Spanish cannabis world different than Holland?

For one thing, we have five big cannabis fairs and the Dutch have just one, the Cannabis Cup. We have sunshine and they have rain. The Dutch coffee shop industry has ground to a halt. We have more than 200 cannabis clubs and the number is growing rapidly.

In Holland, as in Spain, a right-wing government is in power. Here, unemployment is high and the government is scrambling to solve social problems. Here, people are thrown out of their homes if they can’t pay the mortgage, and that’s a bigger issue than cannabis.

Where I live in California there are at least three generations of cannabis smokers — people from 15 to 75. What is the generational picture in Spain?

I have a couple of friends that grew up growing cannabis. They have baby photos in which they’re watering cannabis. Industrial hemp. Then in the late 1970s after Franco, the country had many rural areas that were abandoned. Some of these areas were planted with cannabis.

It depends upon age, one’s profession and geographic location here. Many young people consume cannabis, but it also depends on geography, profession, and actual age. It is common in the society as is reflected in the program Malviviendo. The YouTube series is hilarious! It reflects life today in Seville, Andalucía.

Is smoking the preferred method, or edibles, or tinctures?

Virtually everybody mixes tobacco with cannabis. The habit comes from mixing hashish with tobacco. Edibles and tinctures are few and far between, but concentrates are becoming popular

I think of California’s Proposition 215, the Compassionate Care Act of 1996 as a real game-changer. Do you?

Prop. 215 was huge, a breakthrough, and the momentum it unleashed is still building. It hasn’t come to a head yet. Before 215, people were afraid. They’re less afraid now, though they’re still anxious about paying fines, going to jail, losing their rights, having their name in the paper and being shamed. Those are all big penalties for someone who hasn’t stolen anything or hurt anyone. For the most part, it’s victimless crime. Throughout history, fear is the biggest controller. It works.

What do you hope will happen vis-a-vis cannabis in the next year or two?

I hope that the UN repeals the Single Convention Treaty of 1961 when they meet in Vienna, Austria, in March of 2014. The treaty, signed by member nations, classifies cannabis as having absolutely no medicinal use. The treaty lumps cannabis into the same group as heroin. Next, I think we’ll see more and more states in the U.S. adopt both medical and recreational cannabis laws.

A tipping point will be reached with about 30-35 states — a situation similar to the repeal of prohibition. Scientific research on cannabis will also become popular. Wall Street will invest in the medicinal cannabis industry. Seed sales and information dissemination will continue on the Internet worldwide. Cannabis gardeners around the world will continue to plant more cannabis. It is virtually impossible to stop the life cycle of this ancient plant.

Marijuana will keep its underground character for a while, but it will eventually become legal. The wind is blowing in that direction. Politicians like to be on the winning side and cannabis is slowly winning.

You’ve had a long, close connection to HT haven’t you?

High Times is the first and longest-lived cannabis/drug magazine in the world. It’s had an amazing run; it has lived through drug czars, crackdowns, wild times and very serious times. High Times goes on and on! The High Times website is packed with the latest, vital information. The future is with the Internet. Of course, everyone at High Times knows this.

What’s in your future?

I´m finishing a new cultivation book. It’s been five years in the making and it’s twice as big as Marijuana Horticulture – with both text and images. It’ll be released January 1, 2014. My sites — www.youtube.com/user/jorgecervantesmj and www.marijuanagrowing.com — are growing very quickly and I continue to write for more than 20 magazines in 10 languages.

Hadn’t you said everything that you wanted to say already?

No, not even close. There was so much left out of the “Bible” and so much has changed over the last seven years. For example, we now have much more information about ultraviolet light and its effect on plants. LED (Light Emitting Diode) lamps, HEP (High-Efficiency Plasma) lamps and Induction lamps were not covered in the bible.

What’s new and different to say?

The problem with the new book is there’s not enough paper to include all the new information. I had to cut many subjects down and refer readers to our website forum for more information. Cannabis is a never-ending subject and always changing. It’s universal and certainly one of the most fascinating plants on the face of the earth. Go to Google earth and you can see marijuana everywhere. It’s here to stay.

[Jonah Raskin, a frequent contributor to The Rag Blog, is a professor emeritus at Sonoma State University and the author of Marijuanaland: Dispatches from an American War. Read more articles by Jonah Raskin on The Rag Blog.]

Philosophical and otherwise:

Zombies

By Bill Meacham / The Rag Blog / August 26, 2013

In the copious literature about consciousness produced by philosophers in the past 15 or 20 years we find mention of zombies. A philosophical zombie (as opposed to the slow-witted, bloody, undead ones in the movies who like to eat people) is a hypothetical creature used in thought experiments to elucidate what consciousness is. It is supposed to look and act just like a human being but lack subjective experience.

David Chalmers defines it thus: “A zombie is physically identical to a normal human being, but completely lacks conscious experience. Zombies look and behave like the conscious beings that we know and love, but ‘all is dark inside.’ There is nothing it is like to be a zombie.”(1) As Philip Goff describes it,

A philosophical zombie version of you would walk and talk and in general act just like you. If you stick a knife into it, it’ll scream and try to get away. If you give it a cup of tea it’ll sip it with a smile. It uses its five senses to negotiate the world around it just as you do. And the reason it behaves just like you is that the physical workings of its brain are indiscernible from the physical workings of your own brain. If a brain scientist cut open the heads of you and your zombie twin and poked around inside, she would be unable to tell the two apart.

However, your zombie twin has no inner experience: there is nothing that it’s like to be your zombie twin. Its screaming and running away when stabbed isn’t accompanied by a feeling of pain. Its smiles are not accompanied by any feeling of pleasure. Its negotiation of its environment does not involve a visual or auditory experience of that environment. Your zombie twin is just a complex automaton mechanically set up to behave just like you. The lights are on but nobody’s home.(2)

Sounds a bit ridiculous, right? Why would somebody postulate such a thing? They do so in order to refute the idea that everything is at root physical, that conscious experience is nothing but brain cells firing in certain ways. The notion of a philosophical zombie is a weapon in one of the skirmishes of the ongoing mind-body debate. If we can conceive of such a thing as a philosophical zombie, the opponents of physicalism say, then physicalism must be false. Here is the reasoning:

According to physicalism, all that exists in our world (including consciousness) is physical.

Thus, if physicalism is true, a logically possible world in which all physical facts are the same as those of the actual world must contain everything that exists in our actual world. In particular, conscious experience must exist in such a possible world.

In fact we can conceive of a world physically indistinguishable from our world but in which there is no consciousness (a zombie world). From this (so Chalmers argues) it follows that such a world is logically possible. Therefore, physicalism is false. The conclusion follows from 2 and 3 by modus tollens.(3)

This chain of thought has provoked lots of heat but little light. Can we really conceive of a philosophical zombie or do we only think we conceive of it? If we only think we conceive of it, isn’t that conceiving of it? If we can conceive of it, does that make it logically possible? Does logical possibility have any bearing on what actually exists? Is the concept self-contradictory? Is the argument circular, assuming as a hidden premise what is to be proved?

The questions go on and on. That they can’t be answered should serve as a clue that there is something out of whack in the very foundations of the controversy.

In fact the bickering about zombies is a red herring, a distraction that serves no purpose. The philosophical concept of zombie is not only ridiculous but meaningless. By definition such a zombie is an exact physical duplicate of a human being that acts exactly the same as a human being. Hence, there is no possible way for anyone to distinguish a zombie from a human being.

As William James says, “What difference would it practically make to any one if this notion rather than that notion were true? If no practical difference whatever can be traced, then the alternatives mean practically the same thing, and all dispute is idle.”(4) There is no practical difference between saying that someone is a zombie and saying that someone is a human being, so the distinction is meaningless. The concept of zombie is completely useless.

The distinction between zombie and human being seems to be reasonable only because we mistake experience of subjective (private, internal) objects and events for experience of objective (public, external) objects and events. In both cases we are conscious of something. Because more than one person can be conscious of something objective, we mistakenly act as if more than one person could be conscious of something subjective.

But they can’t. Only one person can be conscious of something subjective, namely the person whose subjectivity it is. We act as if positing an entity that is just like a human being but lacking consciousness is like positing an entity that is just like an able-bodied person but lacking an arm. The two are not at all similar, and it is a kind of category mistake to treat them as if they were.

Because the concept of philosophical zombie is meaningless, it has no bearing on the question of how mind and matter are related. We’d all be better off if we quit wasting our time in idle disputes about it.

[Bill Meacham is an independent scholar in philosophy. A former staffer at Austin’s ’60s underground paper, The Rag, Bill received his Ph.D. in philosophy from the University of Texas at Austin. Meacham spent many years working as a computer programmer, systems analyst, and project manager. He posts at Philosophy for Real Life, where this article also appears. Read more articles by Bill Meacham on The Rag Blog.]

Notes

(1) Chalmers, “Zombies on the web.”

(2) Goff, “The Zombie Threat to a Science of Mind,” p. 6.

(3) Wikipedia, “Philosophical zombie.”

(4) James, “What Pragmatism Means,” p.42.

References

Chalmers, David. “Zombies on the web.” Online publication http://consc.net/zombies.html as of 21 August 2013.

Goff, Philip. “The Zombie Threat to a Science of Mind.” Philosophy Now magazine, #96, pp. 6-7.

James, William. “What Pragmatism Means.” Pragmatism and four essays from The Meaning of Truth, pp. 41-62. New York: Meridian Books, 1955. Online publication http://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/us/james.htm as of 21 August 2013.

Wikipedia. “Philosophical zombie.” Online publication http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philosophical_zombie as of 21 August 2013.

Type rest of the post here

Source /

Posted in RagBlog

Leave a comment

Ron Jacobs : Autumn in America, 1973

|

| Lines at New York City gas station, 1973. AP photo. Image from SeattlePI. |

Fall 1973:

Autumn in America

Tempers were heating up. The nightly news on WABC usually featured at least one story per broadcast of a fight or sometimes a shooting at a gas station.

By Ron Jacobs | The Rag Blog | August 26, 2013

Autumn 1973 was quite the autumn. Personally, I had just moved to New York City to attend college at the Bronx campus of Fordham University. I vaguely recall my first full weekend in New York, checking out the Village and attending a showing of National Lampoon’s production Lemmings at the Village Gate.

Some of the cast members would be household names by 1980: John Belushi, Christopher Guest, and Chevy Chase. I smoked a joint during the show and afterwards took the D Train back to the Grand Concourse. The next weekend I met an older woman who invited a fellow dorm resident and me back to her apartment. We drank whiskey and danced.

Perhaps a week after we danced, the Chilean military overthrew the elected government of Salvador Allende and his Popular Unity party. This is exactly what the international Left had feared. Articles regarding the subversion of the socialist Allende government by U.S. corporations IT&T and Anaconda Copper had been running in the Left and underground press for a while. Of course, these corporations were generously assisted by the CIA and the Nixon White House.

I followed the news with an expectant horror. After the generals attacked the palace, I knew it was over. There was a protest outside the UN building in Manhattan where Angela Davis spoke. The numbers attending were pitifully small. Elsewhere in the world tens of thousands protested. Meanwhile, the junta in Chile continued to round up leftists, journalists and others opposed to the coup.

Copper futures rose sharply. On September 25, the great poet Pablo Neruda was buried by his friends after the authorities refused a state funeral and made it illegal for mourners to attend. Thousands did anyhow. His last poem had been smuggled out of the country to Argentina where it was published. The poem lashed out at the authors of the coup in Washington and Santiago, calling the latter “prostitute merchants/of bread and American air,/deadly seneschals,/ a herd of whorish bosses/with no other law but torture/and the lashing hunger of the people.”

Meanwhile, in the football stadium in Santiago, soldiers and other authorities tortured thousands and killed hundreds, including the popular folksinger Victor Jara. Other detainees were held on an island off the Chilean coast. On September 28, the Weather Underground bombed the ITT offices in Manhattan in protest of the coup. Six days earlier, coup architect Henry Kissinger was appointed Secretary of State.

It seemed like only days later that Egypt, Syria, and a couple other Arab armies attacked Israeli military positions. Within days the television was saying that the Soviet Union was threatening to join the fray while Washington was sending an emergency shipment of arms to Israel. Like most wars, this wasn’t exactly a surprise, but the fact that Israel had not pre-empted the attack was at least unusual.

To add to the sense of crisis, the oil-producing nations instituted an oil embargo against the United States and other nations providing arms to Israel (European nations quickly ended their shipments). Even in Manhattan, there were long lines of cars with their drivers waiting to buy their ration of gasoline at every service station.

Like always, the energy industry would profit no matter what happened. So would Henry Kissinger, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize along with northern Vietnamese negotiator Le Duc Tho. Mr. Tho refused the prize because there was no peace in Vietnam.

In the United States, the situation known as Watergate continued to expand in the way it affected the White House, Congress, and the relationship of the U.S. citizenry to the government. To stave off his critics, Nixon had appointed a special prosecutor, Archibald Cox, whose job was to investigate the possibility that crimes had been committed (even though most of the U.S. already knew the answer) and what those crimes might be.

|

| On September 11, 1973, a brutal military coup led by General Augusto Pinochet swept Chile’s socialist President Salvador Allende from power. Photo by AFP. Image from BBC. |

On October 10, Nixon ordered his Attorney General to fire the special prosecutor. Elliott Richardson, the Attorney General, resigned instead, as did his assistant. However, the man who was third in line at the Justice Department, Robert Bork, carried out Nixon’s order and fired Cox. The shit had barely begun to hit the fan as far as Watergate was concerned.

Thanks to my perusal of several leftist and underground newspapers, I was somewhat aware that students opposed to the military dictatorship of General Papodopoulos in Greece had taken over Athens Polytechnic University. This had followed a series of protests and the conviction of 17 protesters for resistance to authority. The convictions provoked more, larger protests.

After a couple weeks, the army sent tanks through the gates of the university and police chased students off the campus. Around 400 young people died that night and the next day, killed by the authorities. Students continued the protest, while the dictators outlawed numerous student organizations and arrested dozens. Papadopoulos made some efforts to appeal to the students and others opposed to the dictatorship. In response, he was overthrown by another set of military officers opposed to what they saw as a liberalization of Greek society and the protests continued.

A friend from Teaneck, New Jersey, skipped class for a week while he hired himself out to commuters needing gas but not having the time to sit in the growing lines. The price at the pump was slowly creeping up to 59 cents a gallon and rumors of rationing were growing.

Tempers were heating up, too. The nightly news on WABC usually featured at least one story per broadcast of a fight or sometimes a shooting at a gas station. Usually, the incident was provoked because someone jumped in line. Back then, Geraldo Rivera was a local reporter and still had somewhat liberal political leanings. So did a lot of people who would eventually swallow the poison pill offered by Ronald Reagan less than a decade later.

There was an Attica Brigade chapter on my campus. This was a leftist anti-imperialist youth organization connected to the Revolutionary Union, which was one of many organizations arising from the 1969-1970 dissolution of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). They were primary sponsors of the first Impeach Nixon rally in New York that fall and inspired a fair number of protesters to attempt a takeover of the Justice Department at another impeachment protest in DC the following April.

Their battle cry was “Throw the Bum Out!” We all know that the bum was eventually thrown out, only to be succeeded by a procession of more bums, some worse but none much better. This is what so-called democracy looks like, although objectively it doesn’t seem much different from the aforementioned colonels’ junta in Greece or the revolving dictatorship in Egypt. We fool ourselves when we pretend that it is.

[Rag Blog contributor Ron Jacobs is the author of The Way The Wind Blew: A History of the Weather Underground. He recently released a collection of essays and musings titled Tripping Through the American Night. His novels, The Co-Conspirator’s Tale, and Short Order Frame Up will be republished by Fomite in April 2013 along with the third novel in the series All the Sinners Saints. Ron Jacobs can be reached at ronj1955@gmail.com. Find more articles by Ron Jacobs on The Rag Blog.]

Posted in Rag Bloggers

Tagged 1973, American History, Memoir, nostalgia, Pablo Neruda, Richard Nixon, Ron Jacobs, Salvador Allende, Social Protest, Watergate, World History

Leave a comment

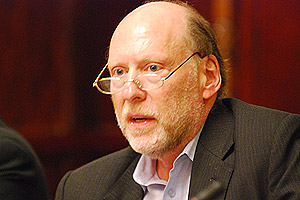

RAG RADIO / Thorne Dreyer : Sociologist Todd Gitlin on the State of American Mass Media

|

| Todd Gitlin. Image from Pew Forum. |

Rag Radio podcast:

Sociologist and author Todd Gitlin on the state of mass media in America

We discuss the so-called ‘Golden Age’ of journalism highlighted by the distinguished coverage of the Watergate scandal, as well as American journalism’s more recent major failures.

Noted sociologist, author, and mass media scholar Todd Gitlin joined host Thorne Dreyer, Friday, August 16, 2013, for the second of two Rag Radio interviews.

Our conversation with Gitlin centered on the history of American mass media, including the so-called “Golden Age” of journalism highlighted by the distinguished coverage of the Watergate scandal, as well as American journalism’s more recent major failures in its handling of Bush’s War in Iraq, the financial crisis, and the continuing issue of climate change.

We also discussed the recent purchase of the Washington Post by Jeff Bezos, and the projected effect of the Internet on journalism’s future.

Rag Radio is a syndicated radio program produced at the studios of KOOP 91.7-FM, a cooperatively-run all-volunteer community radio station in Austin, Texas.

Listen to or download our August 16 interview with Todd Gitlin here:

Todd Gitlin played a pioneering role in the ’60s student and anti-war movements, and in our first interview, originally broadcast on July 19, 2013, we focused

on the lasting legacy of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the Port Huron Statement — including

Gitlin’s critique of the late ’60s New Left — and on the Occupy Wall

Street movement.

You can listen to the earlier show here:

Todd Gitlin is the author of 15 books, including the recent Occupy Nation: The Roots, the Spirit, and the Promise of Occupy Wall Street. He is a professor of journalism and sociology and chair of the Ph. D. program in Communications at Columbia University.

Gitlin is on the editorial board of Dissent and is a contributing writer to Mother Jones. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, and countless other mainstream and alternative publications.

In 1963-64, Todd Gitlin was the third president of Students for a Democratic Society, and he helped organize the first national demonstration against the Vietnam War and the first American demonstrations against corporate aid to the apartheid regime in South Africa.

Gitlin was an editor and writer for the underground newspaper, the San Francisco Express Times, and wrote widely for the underground press in the late ’60s. In 2003-06, he was a member of the Board of Directors of Greenpeace USA.

Gitlin’s other books, several of which have won major awards, include the novel, Undying; The Chosen Peoples: America, Israel, and the Ordeals of Divine Election (with Liel Leibovitz); The Bulldozer and the Big Tent: Blind Republicans, Lame Democrats, and the Recovery of American Ideals; and The Intellectuals and the Flag.

He is also the author of Letters to a Young Activist; Media Unlimited: How the Torrent of Images and Sounds Overwhelms Our Lives; The Twilight of Common Dreams: Why America Is Wracked by Culture Wars; The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage; Inside Prime Time; and The Whole World Is Watching.

Rag Radio is hosted and produced by Rag Blog editor and long-time alternative journalist Thorne Dreyer, a pioneer of the Sixties underground press movement. Tracey Schulz is the show’s engineer and co-producer.

Rag Radio has aired since September 2009 on KOOP 91.7-FM, an all-volunteer cooperatively-run community radio station in Austin, Texas. Rag Radio is broadcast live every Friday from 2-3 p.m. (CDT) on KOOP and is rebroadcast on Sundays at 10 a.m. (EDT) on WFTE, 90.3-FM in Mt. Cobb, PA, and 105.7-FM in Scranton, PA. Rag Radio is now also aired and streamed on KPFT-HD3 90.1 — Pacifica radio in Houston — on Wednesdays at 1 p.m.

The show is streamed live on the web and, after broadcast, all Rag Radio shows are posted as podcasts at the Internet Archive.

Rag Radio is produced in association with The Rag Blog, a progressive Internet newsmagazine, and the New Journalism Project, a Texas 501(c)(3) nonprofit corporation.

Rag Radio can be contacted at ragradio@koop.org.

Coming up on Rag Radio:

Friday, August 30, 2013: Educator and “Small Schools” advocate Michael Klonsky, former National Secretary of SDS.

Friday, September 6, 2013: Award-winning novelist and screenwriter Stephen Harrigan, author of The Gates of the Alamo and Challenger Park.

Posted in RagBlog

Tagged Interview, Journalism, Mass Media, Media Criticism, Media History, New Left, Podcast, Rag Radio, SDS, Sixties, Sociology, Thorne Dreyer, Todd Gitlin

Leave a comment

Posted in RagBlog

Leave a comment

Lamar W. Hankins : The March for Jobs and Freedom After 50 Years

50 years later:

The March for Jobs and Freedom

While King’s ‘I Have a Dream’ speech is clearly worthy of distinction, our memories of the event have shunted aside one of the primary purposes of the March: to push for a $2-per-hour minimum wage.

By Lamar W. Hankins /The Rag Blog / August 24, 2013

[A series of events marking the 50th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedem is being held Saturday, August 24-Wednesday, August 28, in Washington, D.C., highlighted by a Realize the Dream March and Rally on Saturday, 8 a.m-4 p.m., and a March for Jobs and Justice on Wednesday, 11:30-4 p.m., led by veterans of the ’63 event and featuring speeches by President Obama and former presidents Clinton and Carter.]

August 28, 2013, will mark the 50th anniversary of what is now called “The March on Washington,” but was officially named “The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.” I was unable to go to Washington, D.C., 50 years ago, but I remember where I was, and the March was certainly on my mind. A friend and I were on a trip through Houston. We stopped at a Foley’s store and spent some time in the appliance section watching the March on the televisions displayed.

Another friend I had known in high school was working for a federal agency in D.C. at the time. He and his fellow employees were sent home for the day (a Wednesday) because the government feared violence, clear evidence of the state of race relations at the time. My traveling companion and I were pleased to see that the March was as peaceful as its organizers had hoped it would be.

There were stirring speeches by John Lewis, now a Congressman from Georgia, as well as Martin Luther King, Jr. Others well-known in public life were in attendance or sent their remarks to be read by others. James Farmer, head of the Congress of Racial Equality, was in jail in Louisiana. His remarks were read by Floyd McKissick. Author James Baldwin’s remarks were read by Sidney Poitier.

Others, including labor leader Walter Reuther and actor and singer Josephine Baker gave brief speeches. A. Phillip Randolph and Bayard Rustin played key roles in organizing the March, which was supported by the major civil rights organizations active at that time, as well as the AFL-CIO, and other union and religious groups.

Many musicians and singers performed, including Marian Anderson; Joan Baez; Bob Dylan; Mahalia Jackson; Peter, Paul, and Mary; Odetta; and Josh White. Actors present included Charlton Heston, Harry Belafonte, Marlon Brando, Diahann Carroll, Ossie Davis, Sammy Davis, Jr., Lena Horne, and Paul Newman, along with comedian Dick Gregory.

|

| March on Washington, 2013. |

What we hear most about the March was the famous “I Have a Dream” speech of Dr. King. While the speech is clearly worthy of distinction, our memories of the event have shunted aside one of the primary purposes of the March: to push for a $2-per-hour minimum wage.

Had that goal been achieved and a $2 minimum wage been passed and indexed for inflation, the minimum wage today would be $15.26 based on the Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index Inflation Calculator.

It happens that $15.26 is less than what a living wage in San Marcos-Austin-Georgetown would be today for one adult supporting one child. That figure, according to the Living Wage Calculator maintained by MIT, is $19.56 for those living in San Marcos/Hays County, Austin/Travis County, and Georgetown/Williamson County. The Living Wage Calculator takes into account the following costs:

- It uses the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s 2010 low-cost food plan, with regional adjustments. A family of four with two adults and two young children is expected to spend about $650 on food, less than $22 a day for the four.

- Child care costs are determined from a report, “Parents and the High Cost of Child Care – 2011 Update” published by the National Association of Child Care Resource and Referral Agencies.

- The cost of health care is derived from the “2010 Consumer Expenditure Survey” prepared by the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the “2010 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey” published by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

- Housing costs are from “2010 Fair Market Rents” produced by U.S Department of Housing and Urban Development.

- Transportation expenses are from the “2010 Consumer Expenditure Survey.”

- Other necessities are derived using regional adjustment factors from the “2010 Consumer Expenditure Survey.”

- Tax figures include estimated Federal payroll taxes as well as Federal and State income taxes for the 2011 tax year.

These Living Wage calculations show that we are nowhere close to what an inflation-adjusted minimum wage would be had it been $2 an hour in 1963. In fact, we are at less than half that amount with a current minimum wage of $7.25 an hour. And President Obama earlier this year, in the face of strong opposition, requested an increase in the federal minimum wage to a pitifully inadequate $9 per hour.

These facts about what income can provide a minimal standard of living in the U.S. demonstrates that we have an economic system unwilling to provide Americans with a living wage when left to its own devices. But, as we are learning from current efforts by workers at fast food restaurants to be paid adequate wages, the companies that own these businesses are raking in plenty of profits from the labor of workers.

These companies could both thrive and allow their workers to live decently. An undergraduate student at the University of Kansas who researched McDonald’s company-owned stores found that the fast food giant could double all employee salaries by increasing the cost of a Big Mac by 68 cents, without giving up one penny of profits. And Dean Baker, co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, believes that McDonald’s is so large, vast, and lucrative that the company could easily manage a major wage increase for its employees without damaging its profits.

Recently, fast food workers in New York City, St. Louis, Chicago, Detroit, Milwaukee, Kansas City, and Flint, Michigan, have been demanding that they be paid something closer to a living wage and that they be allowed to have the chance to form a union without intimidation by management. They ask to be paid $15 an hour, just under what the 1963 $2 per hour minimum wage demand would be if adjusted for inflation.

As a result of these recent efforts to obtain fairer pay, work stoppages and walkouts have occurred in fast food restaurants in several cities. Their efforts are being aided by the Service Employees International Union and could be advanced further if those of us who consume fast food support them.

If consumers respond to the moral issues related to fast food businesses by refusing to patronize fast food restaurants that won’t pay a living wage to their employees, this movement could finally realize a part of King’s dream and a primary objective of the 1963 March on Washington.

Nothing could be a more fitting memorial to the man who was killed while supporting sanitation workers in Memphis, who sought better wages, than for minimum wage workers throughout the country finally to be paid a fair wage that allows them and their families to live adequately.

[Lamar W. Hankins, a former San Marcos, Texas, city attorney, is also a columnist for the San Marcos Mercury. This article © Freethought San Marcos, Lamar W. Hankins. Read more articles by Lamar W. Hankins on The Rag Blog.]

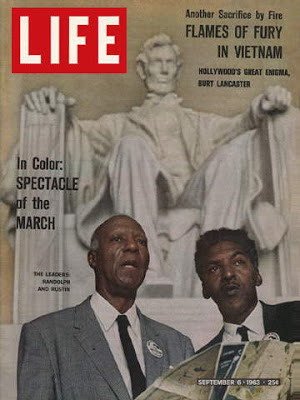

David McReynolds : Reflections on the ’63 March on Washington

|

| A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin on the cover of Life Magazine, September 6, 1963. |

A socialist remembers:

Reflections on the March on Washington

The climate in Washington, D.C. that day was timorous. White Washingtonians feared some riotous upheaval.

By David McReynolds | The Rag Blog | August 24, 2013

August 28th will be the 50th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedem.

Increasingly I realize, at 83, that there just aren’t that many of us around who were there that August day 50 years ago. I knew Bayard Rustin — chief organizer of the March — (and will return to his name in a moment) and like many of us in the War Resisters League, the Socialist Party, and virtually all left organizations, was involved in the organizing for the event.

The decision to hold the March in mid-week rather than on a Saturday was very deliberate: Saturday marches are fairly easy to build, since few have to take time off from work, but a demonstration in the middle of the week means real commitment.

The climate in Washington, D.C. that day was timorous. White Washingtonians feared some riotous upheaval. It was then (and still is) easy for tourists to be unaware that the bulk of the population of the city is black. And what, the white minority wondered, would happen with thousands of angry Blacks coming to town.

Many businesses closed down. President Kennedy had made serious efforts to persuade Dr. King and the March organizers to call off the event. For a weekday the city was remarkably quiet. One must keep in mind the political climate of 1963.

The Civil Rights Revolution (it was nothing less than that) had only begun in December of 1955 in Montgomery. Ahead lay the bloodshed, the murders, the police violence, all of which had brought the leadership of the Black community into agreement on the need for some powerful symbolic action — and that action was the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

It’s important, first, to look at the slogan: Jobs and Freedom. The link was very deliberate — for what was freedom without a job?

I remember three things about the day.

One was the sound of thousands of souls, black and white, marching together toward the Lincoln Memorial, with the chant “Freedom! Freedom! Freedom!” It was truly black and white together. “White Washington” may have been fearful, but the trade unions were out in full force, and church and social justice groups had turned out their congregations and members.

The second thing I remember — and I suspect few saw it — was the failed effort of the American Nazi, George Lincoln Rockwell, to stir up a riot. I give him credit for raw courage: he stood up on a park bench and began an oration against “Kikes, Niggers and Communists.” What happened next was a testament to careful planning on the part of the March organizers. Several dozen young Black youth formed a large circle around Rockwell and his followers, and, with their backs facing Rockwell, linked arms to make it clear that no one would be able to get through to the man and give him the violence he had sought to provoke.

The third thing I remember was King’s speech. Sometimes at these marches and demonstrations — and over the years I’ve attended many — I simply made sure I got to the rallying point so the “count” would be maximized, and then I drifted away for a drink (those being the days when I drank) or a hamburger. There are so many speeches, and they are so boring. But this time I stayed — and remember as if it were yesterday the cadence of King as he spoke, “I have a dream”.

There were, I was aware, compromises; John Lewis, the courageous young Black civil rights leader, had had to to modify his comments a bit. (I suspect Lewis, looking back today, might realize the compromises in his language were much less important than the March itself.)

For Bayard Rustin the March was a great triumph. Life magazine carried a cover with A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin standing together on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

I’ve been invited to take part in a forum at a “Celebration of the Life of Quaker Bayard Rustin ” on Sunday, August 25, at the Friends Meeting in Washington. They will show the film, Brother Outsider, followed by a panel with Mandy Carter, Bennett Singer, and myself.

I’m reluctant to take part, since, while Bayard was a deeply important part of my life — he and A.J. Muste were the two mentors for my politics. I knew him well, and had under him at Liberation magazine and the War Resisters League. But I feel that the political path Bayard took after the March was a disturbing shift to the right, and that this must be discussed if we are to confront his life honestly.

As I said, I’m reluctant to do this since Bayard was one of the most courageous men I ever knew.

In connection with the events this month there is a new book out by Paul Le Blanc and Michael D. Yates, A Freedom Budget for All Americans. Published by Monthly Review Press, the book is due for print in September. (I have the uncorrected proof, which Paul Le Blanc was kind enough to send me.) Bayard had been very concerned that the March would not lead to the next steps, which he felt should be an effort to put forward a political and economic program to give the civil rights movement a “floor,” a program for full employment.

The original Freedom Budget foundered because the authors sought to sell it to the publilc without realizing the need to take on the military budget. From Bayard’s point of view, such an approach would “politicize” the budget and sink it, but in the real world of politics, which somehow Bayard failed to grasp, it was impossible to advance such a radical proposal at a time when the Vietnam War was so soon to absorb the attention of the nation.

It is good to have two socialist thinkers sketch out not only the history of the original Freedom Budget, but also give us an updated look at what such a budget might look like today.

[David McReynolds was the Socialist Party’s candidate for President in 1980 and 2000, and for 39 years on the staff of the War Resisters League. He also served a term as Chair of the War Resisters International. He is retired and lives with his two cats on New York’s lower east side. He can be reached at davidmcreynolds7@gmail.com. Read more articles by David McReynolds on The Rag Blog.

Harry Targ : The CIA’s Iranian Coup and 60 Years of ‘Blowback’

|

| Supporters of Mohammed Mossadegh demonstrate in Tehran, July 1953. Placard depicts an Iranian fighting off Uncle Sam and John Bull. Image from The Spectator. |

The overthrow of Mossadegh:

Sixty years of Iranian ‘blowback’

The overthrow of Mossadegh and the backing of the return of the Shah to full control of the regime led to U.S. support for one of the world’s most repressive and militarized regimes.

By Harry Targ /The Rag Blog / August 21, 2013

Chalmers Johnson wrote in The Nation in October 2001, that “blowback”

is a CIA term first used in March 1954 in a recently declassified report on the 1953 operation to overthrow the government of Mohammed Mossadegh in Iran. It is a metaphor for the unintended consequences of the U.S. government’s international activities that have been kept secret from the American people. The CIA’s fears that there might ultimately be some blowback from its egregious interference in the affairs of Iran were well founded… This misguided “covert operation” of the U.S. government helped convince many capable people throughout the Islamic world that the United States was an implacable enemy.

The CIA-initiated overthrow of the regime of Mohammed Mossadegh 60 years ago on August 19, 1953, was precipitated by what Melvin Gurtov called “the politics of oil and cold war together.” Because it was the leading oil producer in the Middle East and the fourth largest in the world and was geographically close to the former Soviet Union, President Eisenhower was prevailed upon to launch the covert CIA war on Iran long encouraged by Great Britain.

The immediate background for the ouster of Mossadegh was Iran’s nationalization of its oil production. Most Iranians were living in poverty in the 1940s as the Iranian government received only 10 percent of the royalties on its oil sales on the world market. The discrepancy between Iran’s large production of oil and the limited return it received led Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh, a liberal nationalist, to call for the nationalization of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company in 1951.

Despite opposition from Iran’s small ruling class, the parliament and masses of the Iranian people endorsed the plan to seize control of its oil. Mossadegh became the symbol of Iranian sovereignty.

Ironically, Mossadegh assumed the United States would support Iran’s move toward economic autonomy. But in Washington the Iranian leader was viewed as a demagogue, his emerging rival the Shah of Iran (the sitting monarch of Iran) as “more moderate.”

After the nationalization, the British, supported by the United States, boycotted oil produced by the Iranian Oil Company. The British lobbied Washington to launch a military intervention but the Truman administration feared such an action would work to the advantage of the Iranian Communists, the Tudeh Party.

The boycott led to economic strains in Iran, and Mossadegh compensated for the loss of revenue by increasing taxes on the rich. This generated growing opposition from the tiny ruling class, and they encouraged political instability. In 1953, to rally his people, Mossadegh carried out a plebiscite, a vote on his policies. The Iranian people overwhelmingly endorsed the nationalization of Iranian oil. In addition, Mossadegh initiated efforts to mend political fences with the former Soviet Union and the Tudeh Party.

As a result of the plebiscite, and Mossadegh’s openings to the Left, the United States came around to the British view; Mossadegh had to go. As one U.S. defense department official put it:

When the crisis came on and the thing was about to collapse, we violated our normal criteria and among other things we did, we provided the army immediately on an emergency basis… The guns that they had in their hands, the trucks that they rode in, the armored cars that they drove through the streets, and the radio communications that permitted their control, were all furnished through the military defense assistance program… Had it not been for this program, a government unfriendly to the United States probably would now be in power. (Richard Barnet, Intervention and Revolution, 1972)

The Shah, who had fled Iran after the plebiscite, returned when Mossadegh was ousted. A new prime minister was appointed by him who committed Iran to the defense of the “free” world. U.S. military and economic aid was resumed, and Iran joined the CENTO alliance (an alliance of pro-West regional states).

In August 1954, a new oil consortium was established. Five U.S. oil companies gained control of 40 percent of Iranian oil, equal to that of returning British firms. Iran compensated the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company for its losses by paying $70 million, which Iran received as aid from the United States. The Iranian ruling class was accorded 50 percent of profits from future oil sales.

President Eisenhower declared that the events of 1953 and 1954 were ushering in a new era of “economic progress and stability” in Iran and that it was now to be an independent country in “the family of free nations.”

In brief, the United States overthrew a popularly-elected and overwhelmingly-endorsed regime in Iran. The payoff the United States received, with British acquiescence, was a dramatic increase in access by U.S. oil companies to Iranian oil at the expense of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company.

The overthrow of Mossadegh and the backing of the return of the Shah to full control of the regime led to U.S. support for one of the world’s most repressive and militarized regimes. By the 1970s, 70,000 of the Shah’s opponents were in political prisons. Workers and religious activists rose up against the Shah in 1979, leading to the rapid revolutionary overthrow of his military state.

As Chalmers Johnson suggested many years later, the United States’ role in the world is still plagued by “blowback.” Masses of people all across the globe, particularly in the Persian Gulf, the Middle East, and East Asia, regard the United States as the major threat to their economic and political independence. And the covert operation against Mohammed Mossadegh in Iran is one place where such global mistrust began.

[Harry Targ is a professor of political science at Purdue University and is a member of the National Executive Committee of the Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism. He lives in West Lafayette, Indiana, and blogs at Diary of a Heartland Radical. Read more of Harry Targ’s articles on The Rag Blog.]

Posted in Rag Bloggers

Tagged CIA, Harry Targ, Iran, Iranian Coup, Mohammed Mossadegh, Oil Business, Shaw of Iran, U.S. Foreign Policy, U.S. Imperialism

Leave a comment

Michael James : ‘El Lechero’ in San Miguel de Allende, 1962

|

| ‘El lechero’ in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, August 1962. Photo by Michael James from his forthcoming book, Michael Gaylord James’ Pictures from the Long Haul. |

Pictures from the Long Haul:

‘El lechero‘ in San Miguel, 1962

We arrive early and watch people setting up and selling their produce and wares. There are a few vaqueros stumbling up a cobblestone street… I shoot an image of a lechero making his delivery rounds, a container of milk on his back.

By Michael James | The Rag Blog | August 21, 2013

[In this series, Michael James is sharing images from his rich past, accompanied by reflections about — and inspired by — those images. This photo will be included in his forthcoming book, Michael Gaylord James’ Pictures from the Long Haul.]

I’m riding in the back seat of a 1957 Plymouth, heading to Acapulco on a weekend adventure. Cliffs on the mountainside act as pages in the “People’s Book,” catching my attention. Giant messages say: “¡Capitalismo No! ¡Comunismo Si! ¡Viva Castro!” I heard in one of my anthropology classes about leftist guerillas controlling portions of Guerrero, the state we’re riding in.

The car belongs to the Delamarter twins out of Michigan, Larry and Lou. Also on the ride are Bob Marks and a guy named Zeke from Long Island. I credit these four with introducing me to the wilder side of new things I experienced in Mexico.

In Acapulco there’s drinking at a back-street cantina where a little pimp, speaking a few words in five languages, introduces a parade of women. There is a party on a docked sailboat, where the Jamaican captain is very rude to the women he’s invited.

On a more wholesome adventure, we head south of Acapulco to a non-tourist beach, for a great swim in the Pacific. Older women sit on an old boat. A campesino couple is walking the beach. An old man is asleep in a hammacca.

I see Afro-Mexican kids, reflecting the slave economy of earlier times. Years later I will learn the extent to which African slaves were brought to Mexico and Central and South America. And later I will also learn that Mexico abolished slavery in 1829, long before it was abolished in the USA.

Early Sunday morning in Acapulco, at dawn, I’m awakened from a short night’s sleep by the barking of dogs, followed by the earth rumbling and the building shaking. Whoa! It’s short and then it’s over: my first earthquake.

On yet another occasion with the same four fellows, plus another gringo and three Mexican theater types, I take a Saturday trip to San Miguel de Allende. An artists’ colony with a long-running expatriate presence, San Miguel is about 175 northwest of Mexico City. Once a battleground between the Dominican and Franciscan religious orders, there are churches everywhere.

We arrive early and watch people setting up and selling their produce and wares. There are a few vaqueros stumbling up a cobblestone street after an apparent night out. Lots of burros, little beasts of burden, are loaded with bundles on their backs. An old man pulls a small cart, watched by a group of laughing Mexican teenagers modernos. What a contrast. I shoot an image of a lechero making his delivery rounds, a container of milk on his back.

Other new friends I meet at the Mex-Ci-Co apartamentos include Jack and Donna Traylor, and Jim Darby, who years later would become a Chicago public school teacher. Jim, an ex-sailor, had ridden the smallest model Honda motorcycle all the way from Chicago. Part of the trip his brother was riding on back, getting out of town after being shot in the leg.

I would see Jim just once back in Chicago, but after then was never able to find him — that is, until I saw him in 2013 while watching public TV. Jim and his boyfriend were the focus of a story about how they are suing my pal David Orr, the Cook County Clerk, over the right to marry in Illinois. Wow. I ended up contacting him and having him on our Live from the Heartland radio show.

Jack Traylor was an Okie, his family part of the Grapes of Wrath migration that moved from Oklahoma to California in the late 1930’s. He and Donna were schoolteachers and graduate students. And Jack sang beautiful versions of Woody Guthrie songs. He has my favorite voice ever.

In the early 1960’s in San Jose, California, Jack taught Paul Kantner guitar riffs. Later in the 60’s he played with the Gateway Singers and toured the nation’s folk clubs. In the 70’s, his own group, Steele Wind, put out an album on Grunt. The Jefferson Airplane “stole” guitarist Craig Chaquico from Steel Wind. Jack wrote some tunes for Jefferson Airplane, and was the link that brought the Airplane to the Heartland Café 40-odd years later.

Jack and Donna have a VW camper. I ride around with them, and they are the closest thing to parental figures I have in Mexico. They look out for me. Once Jack throws me into the van and speeds off. We’d been drinking at the Tipico Mexico in Garibaldi Square, a place full of bars, mariachi bands, and putas.

A well-dressed young Mexican with a smile asks me — an inebriated, not-very-bilingual gringo — ¿Como se gusta tipico Mexico? How do I like typical Mexico? Thinking he means the bar we’ve been in, where solicitation for sex is constant, I say No me gusta, demasiado putas, “I don’t like, too many whores” — whereupon Jack immediately shoves me into the van; an embarrassing episode to this day.

Mexico City. Wow! What a place. Years later I would become friends with the late, great leftist writer John Ross, who was a regular contributor to The Rag Blog and whose El Monstruo: Dread and Redemption in Mexico City covers the city’s dynamic history from early on.

My activities in La Ciudad that summer of ’62 include eating out, drinking, lifting weights at a Mexican version of a Vic Tanny gym, going to museums, taking classes, reading, writing letters, shopping, and getting the Triumph repaired. And I discover Sanborns.

Sanborns was a lunch counter/soda fountain operation similar to Howard Johnsons in the States. I meet a waitress there, a pretty counter girl in a tan uniform, little hat, and white apron. Getting my courage up, I make a return visit and ask if she would like to go on a date, go see a movie. And she accepts.

So, wearing a sport jacket and driving the Delamarter boys’ 1957 Plymouth wagon, I venture into a maze of unpaved back streets, getting lost in el barrio. Eventually I find her family’s small adobe home, indistinct from hundreds of others. I go to the door and she greets me — with the information that her father won’t permit her to go on the date. She says she is sorry. So am I.

At a party one night at the apartment complex, I am sharing a joint: la mota, la marijauna. I remember seeing this far-out, amazing golden waterfall as I take a piss. In the morning I wake up sick. Really sick. Very sick.

Yellow jaundus, hepititis. I’ve got it. It’s got me. Over the course of the next few days, through one of my dad’s connections (who he had repeatedly asked me to contact) — I end up in the American British Cowdray Hospital. I stay there for 19 days. A benefit is eating big, part of the comeback.

While I am recovering I read a book filled with oddities about Mexico, called A Mexican Medley for the Curious. I read Kerouac’s On the Road. In posession of a portable Olivetti typewriter and probably influenced by Jack’s adventures, I write of my little Mexican adventures. I reference politics, drinking, women, and drugs.

A Panamanian nurse who speaks English and has been very friendly asks if she can read it; I say sure. When she returns a few days later, she hands back my would-be manuscript and leaves without a word, never to return. What? First glimmer of lessons I continue to learn.

For the short remainder of the summer I live with the Delamarter brothers who have moved to a modern apartment off the Carretera Mexico Toluca north of Mexico City College. A general lives next door. We never see him, but we do see his wife — glamorous and modern, a bourgiois woman. Her two small boys come to play; other kids from the neighborhood come around too, checking out the gringos. The sexy neighbor wife has some Afghan hounds and, grinning, looks at us young fellows and asks, “You like my dogs?” Ay-yi-yi.

And then it’s time. Trecking north and back to school, I’m on the Triumph, following the gang of four in the Plymouth. We ride through San Luis Potosi, then the desert and Sautillo, and stop for the night in Monterrey. The next day we ride into dusk, heading to Nuevo Laredo during the night. Suddenly around a curve there are lights: a carnival, people enjoying a festive event. I shoot the picture. We move on, cross the border, and sleep in Laredo on the state side of the Rio Bravo, the Rio Grande.

In the morning we find a bike shop and I arrange to leave the Triumph to be shipped. Post-hepititis, I had been told not to ride the bike. But because Mexican law does not permit me to sell it; if I want to keep it I have to drive it out of the country, doctor’s advice or not.

Then we cross back into Mexico, into Neuevo Laredo for a last-time look around. We walk through the red-light disctrict at noon, observing an abundance of women on the stoops of small shacks, their hair up in curlers.

The gang of four leaves me off at my college girlfriend Lucia’s new family home in Morton, outside Chicago. Her dad and I compete to see who can eat the most jalapeño peppers. A day later I’m hitchiking to Connecticut, somehow via the New York Thruway. A band of Gypsies picks me up in a beater Cadillac convertible. They ask if I have money. “No… I wouldn’t be hitchiking if I had money.”

Late that night I am pretty miserable, sleep-deprived, sort of hallucinating while waiting for a ride near Batavia, New York. I make it home to Connecticut sometime the next day and sleep till the day after that.

It’s good to be home. I talk with my dad. He tells me of his job in a fish cannery in Alaska back in the 1920’s, and lets me know that he had smoked marijauna then. He does encourage me not to smoke it every day.

Against my wishes, Dad had been editing and compiling my letters into what he called “The Mexican Oddyessy of Senior Miguel Gaylord James,” then sending mimeographed copies to family and friends. Years later I am grateful to have that tamed-down version of my summer in Mexico.

[Michael James is a former SDS national officer, the founder of Rising Up Angry, co-founder of Chicago’s Heartland Café (1976 and still going), and co-host of the Saturday morning (9-10 a.m. CDT) Live from the Heartland radio show, here and on YouTube. He is reachable by one and all at michael@heartlandcafe.com. Find more articles by Michael James on The Rag Blog.]

HISTORY / Bob Feldman : A People’s History of Egypt, Part 7, 1917-1921

|

| Scene from the Egyptian Revolution of 1919. Image from Egyptian History website. |

A people’s history:

The movement to democratize Egypt

Part 7: 1917-1921 period — British oppression leads to nationalist revolution and beginnings of a labor movement.

By Bob Feldman | The Rag Blog | August 20, 2013

[With all the dramatic activity in Egypt, Bob Feldman’s Rag Blog “people’s history” series, “The Movement to Democratize Egypt,” could not be more timely. Also see Feldman’s “Hidden History of Texas” series on The Rag Blog.]

Despite the 1882 to 1956 imperial occupation of Egypt by the United Kingdom, until 1914 Egypt was still considered to be a legal part of Turkey’s Ottoman Empire. But after Turkey’s Ottoman dynasty rulers — on October 29, 1914 — allied with Germany during World War I, “the British declared martial law in Egypt” on November 2, 1914, and “imposed censorship,” according to Jason Thompson’s A History of Egypt.

Then, on December 18, 1914, “the British government severed Egypt’s ceremonial connection with the Turks and declared the country a British protectorate, changing its territorial status and regularizing Anglo control,” according to Selma Botman’s Egypt from Independence to Revolution, 1919-1952; and on December 19, 1914, the UK “deposed Abbas Hilmy II” as Egypt’s official ruler “for having `definitely thrown in his lot with his Majesty’s enemies’” and “replaced Abbas with his uncle Husein Kamil, an elderly man, easily managed,” who “was given the title of sultan,” according to A History of Egypt.

But Egypt from Independence to Revolution, 1919-1952 noted how more direct and overt UK imperialist rule after 1914 brought increased national oppression to most people in Egypt:

As World War I progressed, the British became more aggressive in their efforts to control the entire country. In addition to British civil servants who were brought to Cairo to run the bureaucracy, British Empire troops swarmed the larger cities. With the war came high inflation and a degree of hardship that was painful to the majority of the population. In consequence, Anglo-Egyptian hostility deepened… Military authorities forced the peasants to exchange grain, cotton, and livestock for limited compensation.

As A History of Egypt also recalled:

Large numbers of men were conscripted into auxiliary forces such as the Camel Corps and the Labor Corps. Beginning in 1916, desperate for soldiers, the British began drafting Egyptians into the army. The British also conscripted people’s livestock, taking the donkeys and camels that were often necessary for subsistence… The tightness of the British grip on Egypt became glaringly apparent when Sultan Husein Kamil died in October 1917, and the British…altered the terms of succession so that he was succeeded not by his son, who was viewed as anti-British, but by his half-brother Ahmed Fuad…

So, not surprisingly, near the end of World War I an Egyptian “nationalist leader, Saad Zaghlul, with support from the entire country, openly demanded….. that Egypt be allowed to determine [its]own destiny;” and “in November 1918, an Egyptian delegation of nationalist politicians and well-paid notables was formed” — that “became the nucleus” of the Egyptian landowning elite’s nationalist Wafd party — “and prepared itself to represent Egypt at the postwar conference in Paris,” according to Egypt from Independence to Revolution, 1919-1952.

On March 8, 1919, UK authorities in Egypt arrested Zaghlul and his political associates and deported them to Malta. In response to these arrests, according to the same book, the following happened:

Within days, the country erupted in revolt, protesting against the deportation of Zaghlul, the British occupation and Britain’s refusal to allow Egyptian nationalists to represent their country in negotiations to determine Egypt’s postwar status. Students, government employees, workers, lawyers, and professionals took to the streets…demonstrating, protesting… Throughout the country, British installations were attacked, railway lines damaged, and the nationalist movement gained credibility.

And, according to A History of Egypt, “by the time the British rushed in troops and restored order later in the month, more than 1,000 Egyptians were dead from the violence, as were 36 British military personnel and four British civilians.”

Zaghlul and his imprisoned Wafd colleagues were then released on April 7, 1919 — following what became known as the “Egyptian Revolution of 1919” — and were now allowed to attend the post-World War I peace conference in Paris to demand political independence from UK imperialism for Egypt. When the Egyptian nationalist leaders arrived, however, in Paris “the American envoy recognized Britain’s protectorate over Egypt;” and “Egypt’s right to self-rule was not established” in 1919, according to Egypt from Independence to Revolution, 1919-1952.

Although Egyptian labor movement activists and workers joined with nationalist businesspeople in making a nationalist Egyptian revolution in 1919, “the revolution did not produce any movement toward labor reform” in Egypt; “and the alliance between labor and the bourgeoisie quickly dissipated,” according to Tareq Y. Ismael and Rifa‘at El-Sa’id’s The Communist Movement in Egypt: 1920-1988.

Labor organizer “[Joseph] Rosenthal and Egyptian intellectuals committed to the labor movement — among the most prominent were Hosni al-‘Arabi, Ali Al’-‘Anony, Salamah Musa, and Mohammed ‘Abdallah ‘Anan — set out to establish an Egyptian Socialist Party (“al-Hizb al-Ishtiraki al-Misr”) with Egyptian members who would represent the unionized workers,” according to the same book. And in August 1921, they founded the Egyptian Socialist Party.

The Egyptian Socialist Party then opened a party headquarters in Cairo and established branches in Alexandria, Tanta, Shibin al-Kawm, and Mansura. But when the party “applied for a license to publish a newspaper“ it was denied a license “because of its opposition to British and government policy” in Egypt, according to The Communist Movement in Egypt: 1920-1988.

In its August 28, 1921, program, the Egyptian Socialist Party demanded “the liberation of Egypt from the tyranny of imperialism and the expulsion of imperialism from the entire Nile Valley;” and in a December 22, 1921, manifesto, the party also declared that it would “maintain its socialist program” and would “not renounce the struggle against the Egyptian capitalist tyrants and oppressors, accomplices and associates of the tyrannical foreign domination.”

[Bob Feldman is an East Coast-based writer-activist and a former member of the Columbia SDS Steering Committee of the late 1960s. Read more articles by Bob Feldman on The Rag Blog.]