Members of the Mississippi Immigrants Rights Alliance at a rally at the Capitol in Jackson, Miss., Jan. 12, 2011. Photo by Rogelio V. Solis / AP.How Mississippi’s black/brown strategybeat the South’s anti-immigrant wave

Members of the Mississippi Immigrants Rights Alliance at a rally at the Capitol in Jackson, Miss., Jan. 12, 2011. Photo by Rogelio V. Solis / AP.How Mississippi’s black/brown strategybeat the South’s anti-immigrant wave

By David Bacon / The Rag Blog / April 24, 2012

“We worked on the conscience of people night and day, and built coalition after coalition. Over time, people have come around. The way people think about immigration in Mississippi today is nothing like the way they thought when we started.” — Mississippi State Rep. Jim Evans

JACKSON, Mississippi — In early April, an anti-immigrant bill like those that swept through legislatures in Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina was stopped cold in Mississippi. That wasn’t supposed to happen.

Tea Party Republicans were confident they’d roll over any opposition. They’d brought Kris Kobach, the Kansas Secretary of State who co-authored Arizona’s SB 1070, into Jackson, to push for the Mississippi bill. He was seen huddled with the state representative from Brookhaven, Becky Currie, who introduced it.

The American Legislative Exchange Council, which designs and introduces similar bills into legislatures across the country, had its agents on the scene.

Their timing seemed unbeatable. Last November Republicans took control of the state House of Representatives for the first time since Reconstruction. Mississippi was one of the last Southern states in which Democrats controlled the legislature, and the turnover was a final triumph for Reagan and Nixon’s Southern Strategy.

And the Republicans who took power weren’t just any Republicans. Haley Barbour, now ironically considered a “moderate Republican,” had stepped down as governor. Voters replaced him with an anti-immigrant successor, Phil Bryant, whose venom toward the foreign-born rivals Lou Dobbs.

Yet the seemingly inevitable didn’t happen.

Instead, from the opening of the legislative session just after New Years, the state’s Legislative Black Caucus fought a dogged rearguard war in the House. Over the last decade the caucus acquired a hard-won expertise on immigration, defeating over 200 anti-immigrant measures. After New Year’s, though, they lost the crucial committee chairmanships that made it possible for them to kill those earlier bills. But they did not lose their voice.

“We forced a great debate in the House, until 1:30 in the morning,” says State Representative Jim Evans, caucus leader and AFL-CIO staff member in Mississippi. “When you have a prolonged debate like that, it shows the widespread concern and disagreement. People began to see the ugliness in this measure.”

Like all of Kobach’s and ALEC’s bills, HB 488 stated its intent in its first section: “to make attrition through enforcement the public policy of all state agencies and local governments.” In other words, to make life so difficult and unpleasant for undocumented people that they’d leave the state.

And to that end, it said people without papers wouldn’t be able to get as much as a bicycle license or library card, and that schools had to inform on the immigration status of their students. It mandated that police verify the immigration status of anyone they arrest, an open invitation to racial profiling.

“The night HB 488 came to the floor, many black legislators spoke against it,” reports Bill Chandler, director of the Mississippi Immigrants Rights Alliance, “including some who’d never spoken out on immigration before. One objected to the use of the term ‘illegal alien’ in its language, while others said it justified breaking up families and ethnic cleansing.” Even many white legislators were inspired to speak against it.

Nevertheless, the bill was rammed through the House. Then it reached the Senate, controlled by Republicans for some years, and presided over by a more moderate Republican, Lieutenant Governor Tate Reeves. Reeves could see the widespread opposition to the bill, even among employers, and was less in lock step with the Tea Party’s anti-immigrant agenda than other Republicans.

Although Democrats had just lost all their committee chairmanships in the house, Reeves appointed a rural Democrat to chair one of the Senate’s two judiciary committees. He then sent that bill to that committee, chaired by Hob Bryan. And Bryan killed it.

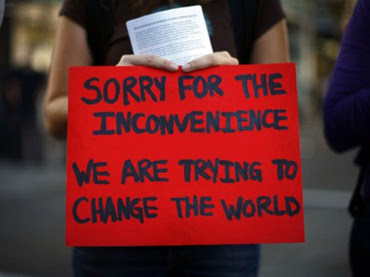

On the surface, it appears that fissures inside the Republican Party facilitated the bill’s defeat. But they were not that defeat’s cause. As the debate and maneuvering played out in the capitol building, its halls were filled with angry protests, while noisy demonstrations went on for days until the bill’s final hour.

That grassroots upsurge produced political alliances that cut deeply into the bill’s support, including calls for rejection by the state’s sheriffs’ and county supervisors associations, the Mississippi Economic Council (its chamber of commerce), and employer groups from farms to poultry packers.

That upsurge was not spontaneous, nor the last minute product of emergency mobilizations. “We wouldn’t have had a chance against this without 12 years of organizing work,” Evans explains.

“We worked on the conscience of people night and day, and built coalition after coalition. Over time, people have come around. The way people think about immigration in Mississippi today is nothing like the way they thought when we started.”

Evans, Chandler, attorney Patricia Ice, Father Jerry Tobin, activist Kathy Sykes, union organizer Frank Curiel, and other veterans of Mississippi’s social movements came together at the end of the 1990s not to stop a bill 12 years later but to build political power. Their vehicle was the Mississippi Immigrants Rights Alliance, and a partnership with the Legislative Black Caucus and other coalitions fighting on most of the progressive issues facing the state.

Their strategy has been based on the state’s changing demographics. Over the last two decades, the percentage of African-Americans in Mississippi’s population has been rising. Black families driven from jobs by factory closings and unemployment in the north have been moving back south, reversing the movement of the decades of the Great Migration. Today at least 37 percent of Mississippi’s people are African-Americans, the highest percentage of any state in the country.

Then, starting with the boom in casino construction in the early 1990s, immigrants from Mexico and Central America, displaced by NAFTA and CAFTA, began migrating into the state as well. Poultry plants, farms, and factories hired them. Guest workers were brought to work in Gulf Coast reconstruction and shipyards. “Today we have established Latino communities,” Chandler explains. “The children of the first immigrants are now arriving at voting age.”

In MIRA’s political calculation, blacks and immigrants, plus unions, are the potential pillars of a powerful political coalition. HB 488’s intent to drive immigrants from Mississippi is an effort to make that coalition impossible.

MIRA is not just focused on defeating bad bills, however. It built a grassroots base by fighting immigration raids at the Howard Industries plant in Laurel in 2008, and in other worksites as well. Its activist staff helped families survive sweeps in apartment houses and trailer parks. They brought together black workers suspicious of the Latino influx, and immigrant families worried about settling in a hostile community. Political unity, based in neighborhoods, protects both groups, they said.

For unions organizing poultry plants, factories, and casinos MIRA became a resource helping to win over immigrant workers. It brought labor violation cases against Gulf employers in the wake of Katrina. Yet despite being on opposing sides, employers and MIRA recognized they had a mutual interest in fighting HB 488. Both opposed workplace immigration raids and enforcement, which are based on the same “attrition through enforcement” idea.

Since 1986 U.S. immigration law has forbidden undocumented people from working by making it illegal for employers to hire them. Called “employer sanctions,” the enforcement of this law (part of the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986), especially under the Bush and Obama administrations, has caused the firing of thousands of workers.

Yet over the last decade, Congressional proposals for comprehensive immigration reform have called for strengthening sanctions, and increasing raids and firings. “That’s why we didn’t support those bills,” Chandler says.

“They violate the human rights of working people to feed their families. For employers, that opposition was a meeting point. They didn’t like workplace enforcement either. All their associations claimed they didn’t hire undocumented workers, but we all know who’s working in the plants. We want people to stay as much as the employers do. Forcing people from their jobs forces them to leave — an ethnic cleansing tactic.”

During the protests Ice, Sykes, and others underlined the point by handing legislators sweet potatoes with labels saying, “I was picked by immigrant workers who together contribute $82 million to the state’s economy.”

MIRA, however, also fought guest worker programs used by Mississippi casinos and shipyards to recruit workers with few labor rights. “When it came to HB 488 employers were tactical allies,” Chandler cautions. Unions, on the other hand, are members of the MIRA coalition.

While MIRA and employers saw a mutual interest in opposing the bill, MIRA helps unions when they try to organize the workers of those same employers, and helps workers defend themselves when employers violate their rights. MIRA, in fact, was started by activists like Chandler, Evans, and Curiel, who all have a long history of labor activity in Mississippi.

When HB 488 hit, busses brought in members of United Food and Commercial Workers Local 1529 from poultry plants in Scott County, Laborers from Laurel, Retail, Wholesale union members from Carthage. Black catfish workers from Indianola, and electrical union members from Crystal Spring. The black labor mobilization was largely organized by new pro-immigrant leadership of the state chapter of the A. Philip Randolph Institute, the AFL-CIO constituency group for black union members.

Catholic congregations, Methodists, Episcopalians, Presbyterians, Evangelical Lutherans, Muslims, and Jews also brought people to protest HB 488, as did the Mississippi Human Services Coalition — a result of a long history working on immigrant issues.

And groups around MIRA and the Black Caucus not only fought that bill, but others introduced by Tea Party Republicans as well. One would ban abortions if a fetal heartbeat is detected. Another promotes charter schools. A third would restrict access to workers compensation benefits, while another would strip civil service protection from state employees.

Dr. Ivory Phillips, a MIRA director and a member of the Board of Trustees of the Jackson Public Schools, explains that charter school proposals, voter ID bills, and anti-immigrant measures are all linked. “Because white supremacists fear losing their status as the dominant group in this country, there is a war against brown people today, just as there has long been a war against black people,” he says.

“In all three cases — charter schools, ‘immigration reform’ and voter ID — what we are witnessing is an anti-democratic surge, a rise in overt racism, and a refusal to provide opportunities to all.”

Tea Party supporters also saw these issues linked together. In the wake of the charter school debate during the same period the immigration bill was defeated, a crowd gathered around Representative Reecy Dickson, a leading Black Caucus member, in which she was shoved and called racist epithets.

“Because of our history we had a relationship with our allies,” Chandler concludes. “We need political alliances that mean something in the long term — permanent alliances, and a strategy for winning political power. That includes targeted voter registration that focuses on specific towns, neighborhoods, and precincts.”

Despite the national importance of stopping the Southern march of the anti-immigrant bills, however, the resources for the effort were almost all local. MIRA emptied its bank account fighting HB 488. Additional money came mostly from local units of organizations like the UAW, UNITE HERE, and the Muslim Association.

“The resources of the national immigrant rights movement should prioritize preventing bills from passing as much as fighting them after the fact,” Chandler warns.

On the surface, the fight in Jackson was a defensive battle waged in the wake of the Republican legislative takeover of the legislature. And the Tea Party still threatens to bring HB 488 back until it passes.

Yet Evans, who also chairs MIRA’s board, believes that time is on the side of social change. “These Republicans still have tricks up their sleeves,” he cautions. “We’re worried about redistricting, and a Texas-style stacking of the deck. But in the end, we still believe our same strategy will build power in Mississippi. We don’t see last November as a defeat but as the last stand of the Confederacy.”

[David Bacon is a California-based writer and photographer. His latest book, Illegal People: How Globalization Creates Migration and Criminalizes Immigrants, was published by Beacon Press. His photographs and stories can be found at dbacon.igc.org. This article was published at web edition of The Nation and was crossposted to The Rag Blog. Read more of David Bacon’s articles on The Rag Blog.]

The Rag Blog