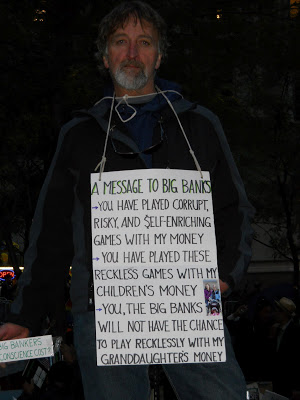

This photo of an Occupier at Zuccotti Park (Liberty Square) was taken several weeks after the footage of police brutality was posted on YouTube and elsewhere. Considering the government’s treatment of the citizenry, the government’s attitude toward the banks and corporations, and the NYPD’s earlier behavior toward the Occupiers and marchers, the sign held special meaning. Yes, screw us, and we-will-multiply. — DN. Photo by Dirk Nelson / The Rag Blog.Occupy Wall Street:

Walking the walk

Some of them carried their messages of anger, hope, contempt, and confrontation while singing songs. Some wore amazing, radiant, eye-twinkling smiles, engaging in uplifting banter, hopeful of tomorrow.

By Dirk Nelson | The Rag Blog | February 9, 2012

[Alaskan activist and writer Dirk Nelson recently traveled to the Occupy Wall Street protest in New York City, serving as a correspondent for The Ester Republic. Below is the first part of his two-part series on what led him on his journey and what he found when he arrived.]

There’d been almost nothing in the mainstream media about this mini-revolution in New York City’s financial district referred to as Occupy Wall Street, not until late September, when MSNBC broadcast the story of NYPD Inspector Anthony Bologna needlessly pepper-spraying three women on a sidewalk during a protest.*

An inflatable rat, or, how I was moved

On the night of October 7th, my friend Ray, his significant other, and I were relaxing at their home in South Anchorage. Ray and I had spent the day standing in front of the Anchorage Daily News with a 26-foot-tall inflatable rat,† a symbol of all that is rotten in the Alaska State legislature’s past dealings with the oil industry.

Lacking high-speed internet services at my home, I’d asked to use Ray’s laptop. What resulted was two or three hours of entranced viewing of the heartfelt protesting near Wall Street, acts of selfless solidarity by people on the opposite coast, and clip after clip of police brutality, often committed for no visibly justifiable reason.

I was both moved and mesmerized by these scenes of chaos, spirited protest, and police violence, to the point that I forfeited awareness of my surroundings. Ray and Rindy had been watching me watching the screen for what must’ve been a very long time.

When it was over, and I was finished, having viewed all that I could stand, I had a sense that someone had slipped something into my water; there was a silence that echoed in my mind, like when one is leaving a concert after hours of incredible volume. The echoes of emptiness and post-apocalyptic quiet were reverberating.

I repeated to myself, over and over, “We’re at ******* war…” I was literally numbed by what I’d seen.

And I knew I had to go to Wall Street.

I had to go.

“Sweetie, I think I have to get myself to Wall Street… Is that OK?”

I continued to be absorbed by the images from Wall Street’s Liberty Square. In the photographs and film clips appeared a cluster, an odd congestion, of makeshift tents and tarps, shoulder to shoulder, where no one would ever suspect such an encampment: Wall Street, USA. Lower Manhattan. The Robber Barons’ lair turned hallowed ground on 9/11/2001.

The overlap of themes moved me. The explosion and subsequent leveling of the grand symbol of worldwide capitalism, melted and collapsed by hatred and vengeful acts of terror, had left unforgettable images 10 years earlier. This same place was now overrun by the residual outcomes of the implosion of domestic markets that had followed those catastrophic events, albeit a decade later and several blocks away.

I shared the videos with my wife and family, and made it clear that as a matter of self-respect, I felt obliged to travel to this event. The thing had slowly become my Mecca. If I couldn’t do this, and stand with those who were actively addressing the underlying causes of much of what I’d worked to change, then I had no right to ever lend an opinion again.

I’d left activism mostly behind me years before, and was feeling stale toward life, angry at the lack of positive social and governmental change, and unwilling to further attempt it myself. However, I knew that if I was going to talk the talk — and I had for many years — then I needed to walk the walk, too.

My host from Ocean Gate, New Jersey, wearing a statement to the Big Banks at Liberty Square, containing his sentiments regarding his daughters’ and granddaughter’s futures, and the corporate looting of America. — DN. Photo by Dirk Nelson / The Rag Blog.

On the Right Path

The way the trip came together reminded me of the tales of Moses parting the Red Sea in fleeing the Egyptians. Doors that rarely opened for me were opening left and right. People offered air miles to help procure my airline tickets. Others offered help for my family during my absence. Still others offered financial support, should I need it.

In one case, I’d called an airline to arrange for my reservations, and while expounding on the reason for my trip, an agent interrupted and asked, “You’re going in support of the protesters, aren’t you?” When I affirmed this, the agent offered to help in any way she could, telling me that if I ever needed air travel and was unable to get where I needed to travel to, she had access to benefits as an airline employee, and could use buddy passes.

I shared my pre-trip experiences with a friend, telling him that these sorts of doors simply don’t typically open like this for me. My friend replied, “When you’re on the right path, doors will open like that.” I took it at face value. Things were aligning in an uncanny manner.

Travel implications

I fretted about the air travel for several weeks. It had been about 10 years since I’d flown on a larger commercial aircraft, and those years had often incorporated political actions, during which I’d not always been congenial in expressing my thoughts toward people in positions of power, especially where the USA PATRIOT Act and other issues were concerned.

I was in contact with a freelance journalist in DC, who instructed me to pre-print my boarding pass at home, being sure to review it for either an encrypted or blatant series of three letter S‘s, as this would be a common feature of someone who was pre-determined to receive extra scrutiny at the gate. He added, however, that he’d received reports of people who were on watch lists experiencing trouble in pre-printing their boarding passes; potentially for this very reason.

I eventually decided that I’d either be scrutinized, or I wouldn’t. The story I’d write would either be about the OWS Movement, or it would be about TSA interfering in the First Amendment and the right of the press to travel to sites of news stories… one or the other.

Just in case, though, I sought out a friend who sent me a copy of the Simon Glik case(1), regarding rights of citizen journalists, just to have as extra ammunition; I made several copies.

During dinner one night, a couple of weeks before my scheduled departure, my youngest son, age seven going on 22, abruptly said, “Dad, I don’t think you should go.” His voice was calm, and unusually mature, almost like another person was inside him at that moment.

I asked if he was afraid that the same violence he’d witnessed on film might re-occur, and if he was afraid for my safety. He said that maybe he was. I promised him that I would do my best not to get hurt, but that sometimes, especially when we get older, there are things that we need to do in order to have respect for ourselves, and that this was one of those tasks for me.

Deadly gels and fish blood

Several calls to the airlines to clarify TSA’s restrictions yielded some cause for cynical humor. I’d been informed that peanut butter is in fact a gel, and that it, as well as jam or jelly, is forbidden.

That settled it; my pup tent, with its aluminum poles, was clearly a potential threat to air travel, and, rather than provoking the wrath of an empowered agent responsible for the safety of All of America, I decided it would be included in my checked bags.

That left the question of how to best prepare an internal-frame pack with numerous appendages for what would inevitably be sadistic treatment at the hands of baggage handlers and TSA agents. The answer, I supposed, was to load the entire pack inside my huge yellow dry bag, complete with salmon blood left over from numerous dipnetting outings. I concluded it was as safe as it could be. After all, what baggage person in their right mind would want to handle a bag with rust-brown dried blood on it?

Four of the five double-batches of moose jerky were completed; seven pounds would have to suffice for the 10 pounds I’d hoped to take with me. A fillet of smoked salmon, the last one in the freezer, was wrapped in a sweatshirt, awaiting its loading into the duffle bag that would be packed last at 5 a.m.

Reality struck sometime around 3 a.m., when it became clear that I was going to have an enormous amount of gear. It was a good thing I’d vanquished any thoughts of not having checked bags. Now the question seemed more one of how many checked bags?

My plane’s departure time was rapidly approaching, and, as is typical of my travel experiences, I was sleep-deprived, and more or less functioning somewhere slightly above the cognitive capacity of a melted puddle of goo. It is in this exact frame of mind that so many of my adventures have been launched. Any trip worth taking is worth taking under the influence of the delirium of sleep deprivation and the stimulation of adrenaline; it’s almost a rule.

Liberty Square on Halloween Day, viewing from the northeast side of the Park. Ben, of Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream fame, had just finished serving LOTS of ice cream to the Occupiers when this photo was taken. — DN. Photo by Dirk Nelson / The Rag Blog.

Heading out: No honor among thieves

Wednesday, October 26

At the TSA security check-point, they x-rayed my bags four times, wiped down the inside of my luggage with their particulate-gathering cloth, asked me to not touch my luggage while they searched it, then wished me well. So polite are their intrusions.

Apparently the moose jerky and salmon, added to the presence of numerous alkaline batteries and wires for the micro-cassette deck I carried, were enough to cause significant curiosity for them. Thank goodness I’d seen fit to stow my pup tent in the checked baggage; no doubt the tent’s poles would’ve appeared far more disconcerting on an x-ray scanner than mere moose jerky and smoked salmon.

I tend to be one of those people who entertain a certain willful compromise to their religious non-beliefs when airborne in anything with a poorly-rated or excessive stall speed. In my subjective opinion, Boeing’s 737’s qualify as one of those otherwise remarkable aircraft that simply needs a wider wing-span, or a lighter payload rating; one or the other.

So settling into the almost-comfortable seat, I began a series of self-talk statements, aimed at precluding the need for a mild sedative. It was too early to drink alcohol without stigma, and I was too cheap to buy a shot, even if the stigma didn’t matter. Stigma was quickly becoming of less and less significance at that moment, but money wasn’t.

I reconsidered my objectives — to fly to a large city, seek out persons unknown to me, and, in an ultimate act of defiance, pitch a questionable, 25-year-old pup tent somewhere near Wall Street, without a camping permit, in an area where the New York Police Department had recently cracked skulls for people refusing to get back on the sidewalk.

I wondered if it was too late to disembark the aircraft. The ticket was likely cancellable, but oh, the humiliation of retreat. I ran the hypothetical call to my wife though my mind’s ear: “Honey, I changed my mind. Can you pick me up at the airport?”

Nope, there was absolutely no way to pull that off without a dozen proverbial eggs running down my face, insufficient grace to absorb such shame, and the potential loss of what little self-respect I maintained leaking down my leg. I remained in my seat, as we pushed back from the gate. Newark, here I come!

I tried to get my mind into the perspective I believed this trip would require. Contemplation of the impact of mega-corporations on would-be democratic processes, in a constitutionally-defined republic that was initially founded by folks who distrusted such critters. It all seemed so upside down.

Huh.

Passengers walked up and down the narrow aisle to the restrooms, once we approached cruising altitude. I noted the number of them wearing name-brand casual wear, sporting logos from the major sources. I wondered how many premium-priced garments were the results of shoddy workmanship, or Bangladeshi and Burmese sweat shops. How did we become a culture that offered itself up as walking billboards, translating name-brand shopping trends into self-esteem, and social prestige?

Whatever my reservations, I was off; heading for what at times seemed, intuitively, like ramping up for a final stab at a meaningful life, at a life with magic and promise.

The sun was setting as we headed east over the farm fields of eastern Washington, across the Rockies, the plains of eastern Montana, and into the Midwest. I thought about the distance and the view; people had traveled this same route, in reverse, hundreds of years ago, seeking a New Beginning, hopeful of something more promising than what they’d left behind. I was now traveling the opposite direction, but for similar reasons.

I considered that I was ultimately headed to Manhattan, in an area allegedly purchased for some beads and trinkets, a few blankets, and who-knows-what-else. I wondered if there was something about this place that attracted swindlers and land sharks. By all appearances, it seems to have a lengthy history of supporting just that: people engaged in graft and high-stakes theft, taking something for nothing, or next to nothing.

Oh, the continuity of it all: from the early settlers’ journeying west, the pursuit of dreams, the taking of others’ resources, and more. Sometimes the change only appeared to be a matter of what mode of transport was employed, or the machinery now used to farm those same fields below.

I thought about my Irish ancestors arriving in this country in the 1700s, seeking their dreams like others. They’d headed west to Indiana, and farmed the land with their bare hands, creating a legacy. This whole thing, this whole history, was connected suddenly.

And there were still those same swindler types in Manhattan, trying to get large tracts of real estate, and other forms of wealth and power for a few beads and trinkets; now from their own people. No honor among thieves. Nope, there’s no honor among thieves.

The brutality had taken a bench for a while, and some of these officers, though ordered by their command not to speak to the press, were genuinely patient and kind. — DN. Photo by Dirk Nelson / The Rag Blog.

Arrival

The aircraft began its descent into Newark a half-hour before our arrival. The clear skies facilitated a view of the area for the last 150 miles or so. Other than the Atlantic Ocean to the east, there was some form of urban lighting nearly as far as the eye could see, though I admittedly don’t have the best of eyes. I was sure of one thing; I wasn’t even on the ground yet, and I already felt quite disoriented.

John, my host for the next week, pulled up near the arrivals door, and I threw my gear into his truckbed. Over the next 60 miles to Ocean Gate, New Jersey, we acquainted ourselves, contrasted political and philosophical ideas, and intermittently discussed the history of the land and communities we passed through en route to his home.

Seeing the sights: Cranberries, oysters, and the Tea Party

Thursday, October 27

The day began later than hoped for, though we’d already anticipated that it would. Instead of a late start into NYC, we toured cranberry bogs that have produced berries for centuries. I munched on a couple of ripe cranberries we picked in the field, and walked back to the truck, while John and I bantered briefly about the increased costs of buying locally-made products, and not feeding the corporations that are steadily assisting in displacing the production of goods in the U.S.

We spent that afternoon on the New Jersey Boardwalk, near the white sand dunes and frozen ferris wheels, and visited barely-open-for-business pizza shops, seafood restaurants, and pubs, while I made telephone calls to Alaska’s federal representatives in DC, trying to arrange times to visit their offices next week.

I wasn’t prepared to conduct interviews, but then, life doesn’t always provide for proper preparation, either. My immediate mission was to locate some decent oysters on the half-shell. We stopped into a bar my host once frequented in days gone by, where we ordered two coffees and a half-dozen fresh oysters on the half-shell; three each.

A gray-haired gent nearing John’s age sat next to us, and as we consumed our oysters, he made small talk with us in reference to the news. I decided to interview him, in an effort to get a head start on the assignments for the coming days.

His name was Raymond, 60-years-old, a Vietnam veteran, drafted in the later 1960s, divorced: he’d lost his wealth, his business and his marriage when he tried to better himself by building a small-boat harbor, a project which had eventually failed.

Raymond described himself as a Tea-Party-supporting Republican, tired of corrupt politics, tired of people wanting hand-outs, and inherently offended by what he believed the Occupy Wall Street Movement stood for — based on what the mainstream media had broadcast about it. He said he loved his country, and still viewed it as the best place on earth, despite it needing some fixing.

Ray seemed offended by the high-quality food being consumed by the Occupiers, apparently unaware that all of their supplies were a result of voluntary donations, prepared by volunteers. It was obviously more a matter of envy in that regard than a matter of ethics involving government subsidies; they weren’t eating government food.

The banter remained friendly, and I asked Ray what it was he thought would make America better. He agreed that shareholders ought to have a more direct say in corporate operations. He believed that those who gave themselves huge bonuses from the TARP monies(2) should be held accountable, but pointed out that the looseness of expectations in the granting of those loans had created a circumstance in which giving CEOs obscene bonuses had violated no laws.

Raymond wanted politicians to stop stumping for re-election, posturing, and get down to addressing the country’s ills. He wanted term limits, and for politicians to stop catering to special interests.

By this point, Ray had downed more than a couple drinks, and I stopped him, asking him if he was aware that in many ways, he had just agreed with some of what the Occupiers were saying.

He stopped, stunned for a moment, and retorted, “Well, I guess I have to agree with somebody sometime.”

My resistance to Ray’s buying me a beer finally collapsed, and a pint of Guinness was placed in front of me. I considered the history of the Irish and Italians in this place. Ray was Italian, and I am, in part, Irish. We both came from groups once poorly welcomed into this country. Here we sat, drinking beer, curing the world’s ills, and making peace, one person at a time.

John broke the news to Ray that I was down from Alaska to write stories about the Occupy Wall Street Movement, and that we intended to go to Manhattan the next day to both participate, and march on several of the banks. Ray expressed pleasure and interest in exchanging ideas with someone from Alaska, and teased that he ought to go with us to Zuccotti Park for “some of that really good organic breakfast.”

For a moment I thought it all seemed strangely plausible, this odd group of characters traveling together. I knew we’d make that trip without Raymond, though I was grinning about our having broken down barriers established by the Talking Heads and Partisan Dividers; we’d established a camaraderie with Raymond, and he, and we, had come to realize our agreements outweighed our differences.

The marchers of Group 2 en route to the banks on the “mail delivery” list, Friday, October 28, 2011. — DN. Photo by Dirk Nelson / The Ester Republic.

Turnpike to the library

Friday, October 28

The New Jersey Transit bus to New York City leaves Toms River, New Jersey, at regular intervals throughout the day, returning as frequently as it departs. Arriving at the Toms River transit stop, we purchased our tickets, promptly forgot to pay the parking fee, and boarded the bus to our first day among the Occupiers. It was a promising, sunny day, and our spirits were in good shape.

The Occupiers had planned a protest march for this day, targeting five of the banks that had received TARP funds, and which were accused of unethical or questionable performance. My objectives for the day included getting oriented to New York City, marching with the protesters, obtaining some photos, and taping interviews. After that, we planned to visit Liberty Square (a.k.a. Zuccotti Park). We’d return by bus to New Jersey later in the evening.

Sitting across the aisle from each other, we passed the time with political and personal banter. We spoke of Alaska, where John had just returned from visiting his daughter. We spoke also of the Movement’s various themes, such as equal opportunity, equal protection, and ending corrupt government.

At our destination, the New York City Port Authority, a woman named ’Nita, who’d shared my seat, inquired about Sarah Palin. Not an uncommon inquiry in the Lower 48, where many offered their opinions of our former part-term Governor. Even Raymond, in Lavallette, had offered his views on Sarah. It seemed that she was nothing if not controversial and at least a little bit well known.

I replied that though I hadn’t voted for Sarah, I thought she’d helped to address at least some of the oil-related corruption Alaska has endured, even if Sarah’s efforts were, in my opinion, a product of other motivating factors; more ego-related than not.

’Nita expressed support for the Wall Street Occupiers, and wished us luck.

These New Yorkers didn’t seem so harsh after all.

We eventually made our way to the New York City Public library at 42nd Street and 5th Avenue; the gathering place for the march on the banks that OWS had advertised on their main webpage. We were early, so I ventured into the Library to inquire about public-use computers and internet services. The library’s staff was extremely helpful, and, in less than 15 minutes, I’d obtained a 90-day temporary library card. John and I met outside, and we headed off to gather on the Library’s 5th Avenue steps, waiting for the march to begin.

A blurred shot of OWS protestors sitting on the sidewalk in front of Chase Bank. — DN. Photo by Dirk Nelson / The Rag Blog.

The march

Following a brief gathering for purposes of describing routes and distributing emergency telephone numbers, such as legal counsel, members of the Occupy Wall Street Movement, the Yes Men, and others, marched in two separate groups to a total of five banks in mid-town Manhattan. The two groups delivered over 6,000 letters, written by people affected in various ways by banking practices alleged to have contributed directly to the suffering of those who’d penned the notes.

At each bank’s location, members gathered near a main entrance, on the sidewalks, and chanted “You’ve got mail! You’ve got mail!”

The banks’ perimeters were ringed with metal mobile barricades resembling movable bicycle racks. Also present were varying numbers of a combination of private security and NYPD.

In addition to the police officers stationed at the banks in question, the marchers were escorted by an impressive number of New York’s uniformed and plainclothes police force. Nearly all officers displayed far greater restraint and respect than they had in late September and early October, when unnecessary brutality was at times quite visible in film clips; actions that had originally fueled my early intentions to travel to Manhattan.

As I walked along the route, a uniformed, blue-shirt officer paced to my left. I asked her if I might request an interview. She replied, “We’re not allowed.” She smiled, and I returned the unspoken acknowledgement that there are sometimes factors in our lives that we tend to accept rather than question, despite what else we may know, feel, or believe.

But it was also the first formal acknowledgement of what I’d suspected for a while; for a variety of reasons, some legitimate, and some maybe not, NYPD was attempting to strictly control the flow of information from its ranks. Not uncommon within hierarchically-structured systems, but still disappointing to those of us who desired to obtain as informative an accounting as possible. And that was what I wanted. I wanted to obtain as many personal views and opinions for this series of stories as I could gather.

I had arrived in New York City disappointed, like many others, that NYPD Inspector Anthony Bologna had merely received a loss of 10 days of vacation for his well-documented brutality, when numerous cameras had recorded the pepper-spraying of three women who were already inside a police containment fence, and were breaking no laws. His actions were particularly egregious in light of his alleged history of violating the rights of protesters in 2004; an incident that was still unresolved after seven years.

As far as I know, Inspector Bologna was not present with our group on October 28, 2011, and I was pleased that his type of officer appeared to be far away. It meant the First Amendment would be better respected on that day, and it lessened my anxiety about the potential for the police-generated violence that had been so common just two or three weeks before.

As the groups chanted various rhymes and rhythms, they walked from bank to bank. Our police detail maintained its presence, forming lines around our perimeter, ahead, to the side, and behind.

At one point I turned, holding my camera over my head, intending to get a photo of the crowd behind me, only to find approximately 15 NYPD blue-shirts immediately to my flank. I was well protected, no longer feeling compelled to continue checking for my wallet and ID, though I’d earlier been amply warned of the risks of being pickpocketed in this City.

In two instances, personnel from banks met our groups’ members in front of their respective buildings to accept their stacks of “mail.” One bank employee said he was there to keep the letters off of their patios and sidewalks, preventing littering. At least they were accepting them.

I submitted a letter of my own, regarding lending rates; comparing those charged or offered to persons who need the money most versus the rates charged to persons who don’t, and the issue of taxpayer subsidies in the way of TARP money. I asked in the letter how they are able to sleep at night while they routinely display such a disconnect between their actions and their customers’ needs. Maybe I’ve already answered my own question.

I attempted to engage the gentleman receiving the letters at Wells Fargo in a discussion on the shady activities that some banks and investment firms had reportedly been caught engaging in. I mentioned that Citibank had been fined $285 million for such scams, and that they, among others, were repeat offenders, meaning that there is also a criminal issue of contempt of court in such cases.

He replied that he didn’t know anything about that.

Liberty Square in Lower Manhattan on Halloween. This gentleman’s sign expressed the sentiments of those of us who see the destruction brought by a corporate media skewing the information that the voters rely on to make vital decisions. — DN. Photo by Dirk Nelson / The Rag Blog.

In Citibank’s case, it appeared as though their attorneys had drawn out the investigation until the statute of limitations had expired on some charges. They’d apparently skillfully avoided what were likely deserved criminal convictions.

Despite their crafty avoidance of criminal penalties on the fraud charges, getting away with fines only, it was my understanding that the issue of contempt might still be fresh enough to pursue. And at least one New York federal judge was reported to be looking at this issue, and was critical of the Security Exchange Commission’s long-term embedded relationship with many of these serial offenders who lose their investors’ money while filling their own pockets.

I replied to the bank’s protector, “you’re merely hired as security, right?” We both grinned and winked. Everybody needs a job, and I was attempting to discuss decisions that are made way atop that building, in rooms the gentleman I was addressing probably only visits for two or three minutes at a time, during which he’s likely extremely respectful. Everybody’s got to eat.

In some cases, upon hearing refusal from the banks to accept the letters, marchers folded their sheets of grievances into paper airplanes, throwing them toward the upper windows of the offices in question; a symbolic flight to places still unreachable, though maybe not for long.

In all, the NYPD escort — blue-shirts, white-shirts, and undercover officers — accompanied the two groups to Morgan-Stanley, Chase, Citibank, Wells Fargo, and Bank of America — all alleged Big Players, in one way or another, in the myriad of questionably ethical banking practices.

There was naive idealism and love in the eyes of the youngsters, for many of whom there is a clearly defined line that separates right from wrong. Not a less-pure, rationalized, self-gratifying right and wrong, but a more honorable and deep belief; whether embraced by convention or not.

There were also older, seasoned veterans of many years of trials and tribulations — from the streets and tear gas memories of the 1960s anti-war movement, to graduates of the back-to-the-land movement of the decade-and-a-half following the end of the Vietnam Police Action, where some failed as self-sufficient farmers, and some succeeded, most all of them turning away at that time from mainstream America’s less satisfying direction.

And there were others — teachers, landed immigrants, hotel workers, those out of work and uninsured — who experienced health problems that changed the course of their lives, and more.

There were people who’d lacked a sufficient financial buffer in a specific time of need, those who’d lacked familial support and the financial security that otherwise makes such crises more tolerable. There were people who claimed to have been misled by banks, having been promised future refinancing on high-risk, high-interest loans that never came to pass, despite making their best, most honorable efforts, staying in good standing for terms in excess of those initially prescribed by the lenders.

People who believed, however naïvely, that what a person promises with a handshake matters at least as much as what is hidden in the fine print. People who still cling, however incorrectly, to an America where that was once true.

Some of them carried their messages of anger, hope, contempt, and confrontation while singing songs. Some wore amazing, radiant, eye-twinkling smiles, engaging in uplifting banter, hopeful of tomorrow. If this was some sort of domestic warfare, I believe we all could use a stout dose of it.

We returned to the Library, conversing as I walked alongside a school teacher, a former back-to-the-land farmer and Vietnam era peace marcher. He and I spoke about hunting moose, and feeding my family the old-fashioned way. I offered him a piece of moose jerky. He declined, being committed to vegetarianism, but asked if he might take a couple pieces to his son, who he assured me would appreciate it.

Arriving back at the Library, we loaded the banners into a van belonging to one of the Yes Men, Mike Bonano. He apologized for the banners taking up so much space that he couldn’t offer rides back to Liberty Square. Instead he gave John and me copies of The Yes Men Fix the World, a sort of documentary detailing their own creative efforts at bringing accountability to some of the more notorious offenders in the history of corporate wrongdoing, including Dow Chemical and Union Carbide in their roles related to the Bhopal, India disaster.

Chase Bank employees gather at the windows to take pictures of the OWS crowd, some of whom are photographing the bank employees. “Who’s in the cage?” — DN. Photo by Dirk Nelson / The Ester Republic.

Night at the park: Liberty Square

It had already been a relatively full day when we entered Liberty Square from the northeast corner. It was our first venture into the place that had filled the headlines of so many news outlets with so much disinformation. It was nearly dusk, and we were already tapped from the day’s marching.

Liberty Square is a roughly half-acre park consisting of concrete tiles and sections of slab, surrounded by a barrier of horizontal granite of modest height. There was a serious presence of mostly unnecessary and apparently bored NYPD officers; some wearing helmets, but most just in their blue uniforms, with the exception of those in positions of authority, sporting the white shirts of the inspector class.

Undoubtedly, there were also others present, in plain clothes, representing more subtly a variety of law enforcement and intelligence agencies. It’s amazing how much attention is brought to bear on people questioning the status quo in this society. The prospect of change is clearly perceived as dangerous to some.

The park is a relatively narrow rectangle, running predominantly east to west, perhaps 40 or so yards north to south, and 80 yards east to west. Various cafés, bank buildings, offices, residential apartments, and businesses surround the area. At the west end was the drum circle and what appeared to be a Sikh, dressed in white robes and leading a prayer meeting.

All around, and mingling among the crowd of protesters, were tourists of one flavor or another; people who’d come for the solidarity that the movement represented, as well as those who had simply read about the spectacle, as one Egyptian gentleman would refer to it, and had come to take photos, or at least buy a t-shirt and claim to their friends to have been present.

Representatives of the media, both mainstream and fringe elements, were in abundant presence. Everyone wanted a story. Lights, cameras, clipboards, tape recorders, people asking questions — and those who were willing enough to respond to them — dotted the area.

In the middle of the park was the food tent. There volunteers routinely accepted pre-prepared meals and snacks brought in from the kitchen of a local church. Lines formed to the west, and people received a selection of dishes during meal time.

At the northeast corner was the Occupy Wall Street library, consisting of shelves and totes filled with books, marked by a pole or two with signs on them, all of which defined the library’s presence.

My initial view of the gathering brought to mind the words “chaotic, political activist, and carnival.” Many different causes were represented among those standing around the perimeter of the Square, and among those within its boundaries. Tents of various sizes covered the majority of the Square from one end to the other, often with barely enough room to move between them. Near the library was a tiered area that formed steps leading downward to the center of the Square. It was on these steps that the General Assembly was conducted on a daily basis.

For all of the hype in the mainstream media about hippies, nudity, property damage, pot smoking, and more, I saw none of that. Moreover, I detected the sweet aroma of burning cannabis only one time, and not in any significant quantity, if my olfactory senses were correct — my nose being fairly accurate in this regard.

No, there were no skirmishes between protesters and police, no thrown rocks or bottles, no nude protesters flaunting body parts, no one defecating on the sidewalks or on police cars; none of that. The greatest excitement came from sincere conversations with activists representing their causes, accompanied by earnest smiles, warm handshakes, the occasional costume relative to their presentation, and the food carts’ aromas wafting into the air; falafels, kabobs, pretzels, and more speckled the sidewalks, creating an aromatic buffer between the police presence and the political display known internationally as Occupy Wall Street.

We’d arrived perhaps an hour or so before the beginning of the General Assembly: a sort of parliamentary gathering, conducted via a direct democratic process. We initially encountered a variety of people lining the granite barrier, some of whom were standing on the barrier itself.

One particular couple grabbed my attention. The woman held a sign opposing the extraction of natural gas by means known as “fracking,” a process of extracting natural gas from subterranean rock strata by applying pressurized water. Upstate New York sits atop a major aquifer that holds surprisingly clean water and that supplies all of the city’s drinking water.

The woman holding the sign was partnered with a gentleman of smaller physical stature, wearing a Grim Reaper robe and hood, along with an older-vintage gas mask; he was acting out what appeared to be a t’ai chi exercise, which took on an eerie aura as I watched.

We walked west, along the Square’s north boundary. At the northwest corner, across the street, I noted the NYPD crowd management and observation tower, a mobile scissor-jack device capable of rising above the crowd’s altitude by approximately 15 feet, which supported a compartment containing one or more officers equipped with one-way mirrored glass, microphones, camera lenses, and more.

Big Brother has some neat toys indeed, apparently capable of recording events, faces, and who-knows-what-else. The whole thing was fittingly situated across from the previously-mentioned Sikh, engaged in leading his prayer meeting; the Supreme Being meets the Want-to-Be-Supreme Beings: a tag-team match if ever there was one.

Fortunately the police seemed less interested in interventions involving benign actions that day, so the real conflicts would have to wait for a week or two.

At the west end we briefly paused to watch the drum circle, momentarily stopping again a few yards to the south, where a young woman perched atop the granite barrier, perhaps five and a half feet off the ground, collecting donations for “free coffee.” The coffee was all gone for the moment, though the flower pot for donations was still in operation.

I asked her where she was from, and she replied, “Bakersfield.” Like myself, she’d come all this way for some purpose. I didn’t ask why. She said someone had gone to get more coffee, and accepted my $1 donation, though at that point I no longer expected a cup of java.

I ventured into the cooks’ food tent, and left the first of three bags of moose jerky I had brought to leave with the folks there, thanking them for their efforts and convictions.

My host and I headed to a café across the street for the coffee we still hadn’t acquired. We noted the restroom door had a sign declaring the facilities were out of order; a common sight in the neighborhood since Occupy Wall Street’s stay had begun, though New York City is notorious for lacking public restrooms.

The night was coming to a close, and we still needed to get to the NYC Port Authority to catch our bus back to New Jersey, note pads full of observations and the recorder satisfied with numerous interviews.

What a day.

More to come.

[Alaska resident Dirk Nelson is a correspondent for The Ester Republic. A former clinical social worker and marriage and family therapist, he has been active in drug law reform for 30 years, was a founder of the Fairbanks Bill of Rights Defense Committee, contesting the USA Patriot Act, and has become an active supporter of the Occupy Wall Street movement. A version of this article was originally published at The Ester Republic, “an irreverent periodical published monthly in the Ester Commonwealth [of Alaska] and written by members of the local populace and the odd guest columnist.” Ester Republic publisher and editor Deirdre Helfferich contributed to its original editing.]

* Reportedly, this sort of behavior is not new for Mr. Bologna; he’s alleged to still be involved in court activity regarding his brutalizing protesters at an anti-GW Bush rally in 2004. (How a person extends the processing of basic brutality charges in any court over a period of seven years was somewhat befuddling for me. I assumed it involved status, money from the police union, and a corrupt system that fails to properly discipline its employees.) Further note: Bologna was suspended from the police force for ten days for this incident.

† See Citizens For Ethical Government, http://citizens4ethics.com, and the video coverage at KTVA, “Protest Over Oil Taxes Coverage,” October 7, 2011, available on line at http://www.ktva.com/home/outbound-xml-feeds/Protest-Over-Oil-Taxes-Coverage-131378053.html.

1. See the Citizen Media Law Project, www.citmedialaw.org/blog/2011/victory-recording-public, and the text of the Fist Circuit US Court of Appeals decision, www.ca1.uscourts.gov/pdf.opinions/10-1764P-01A.pdf.

2. TARP: Troubled Asset Relief Program, a program of the United States government to purchase assets and equity from financial institutions to strengthen its financial sector that was signed into law by President George W. Bush on October 3, 2008. It was a component of the government’s measures in 2008 to address the subprime mortgage crisis, as part of the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act.

The Rag Blog