The North Block entrance to Condemned Row at San Quentin. Image from Strong as an Ox.‘Chief’ Stankewitz:

Born on death row

Chief has now spent 33 years of his life on California’s death row, but virtually all of his life before arriving there was spent under the ‘supervision’ of the state of California.

By Steve Russell / The Rag Blog / October 13, 2011

Capital punishment, the saying goes, means that those without the capital get the punishment, and over 35 years of labor in criminal law has yet to show me a case that disproves it.

Capital cases are usually defended by court-appointed lawyers, because prosecutors do not typically choose to seek the death penalty against defendants who can afford the stratospheric legal fees of a capital defense. The only capital case I defended in private practice was one of the very few I’ve seen where the lawyers were hired rather than appointed, and we won — victory being defined in that instance as the government was not allowed to kill our client.

Death row, like most poor neighborhoods, has a disproportionate number of minority residents. Those of us who come from poor neighborhoods know that there are mean people there, and plenty of conditions that make even good people mean. We also know that the vast majority of poor people survive those conditions without becoming mean.

Good or mean, the hearty survival rate of poor people justifies in the minds of some what they call “putting down the mad dogs,” in spite of the fact that it is much more expensive to kill sociopaths than it is to lock them up without the possibility of parole. Those are the two choices for dealing with the people who have become too dangerous to live among us, and such people do exist — in all my years of practice, I have had contact with three of them; three out of the thousands of criminal defendants with whom I have dealt.

Based on my many years in the legal system, I do not trust it to pick those three sociopaths out of a crowd. Sociopaths, you see, are not always poor people — some of them are even white. Back in the days (within my lifetime) when we had the death penalty for rape, those executed were most often dark-skinned men accused of raping white women, and thanks to DNA exonerations we now understand that cross-racial identification is highly unreliable.

Even utterly certain eyewitnesses make mistakes, and confessions are so notoriously unreliable that everyone understands why police investigators withhold some details of every crime that makes the newspaper. The more publicity the crime gets, the more disturbed people will line up to confess.

Making things even more confusing is that confessions by persons actually involved in a crime are often given to shift blame, leading to the perverse outcome in some capital cases that the more experienced criminal is able to make a deal to escape the death penalty by testifying against a less savvy co-defendant, without regard to which defendant was more culpable.

Since eyewitness identifications and confessions can be unreliable, it’s easy to see why there are very few trials where everybody agrees on what happened. What may appear crystal clear in the newspapers can only be seen in the courtroom as through a glass, darkly.

A lawyer’s first duty in a capital case is to tell the best story that can be told with the facts as they stand. If you are a juror in such a case, you have buckets of messy facts brought into the courtroom and must listen to lawyers who assemble stories from those facts — often without regard to what they may believe to be the truth.

A lawyer’s second duty in a capital case, should the first not be discharged successfully, is to make absolutely sure that the jury fully understands the life they are being asked to end. Jurors are introduced to a man by way of the worst thing he’s done in his life, a circumstance that would be a mighty challenge to any of us, even if the task were less vital than to befriend 12 strangers who have nothing in common but their sworn willingness to kill you if the government gives them a good enough reason.

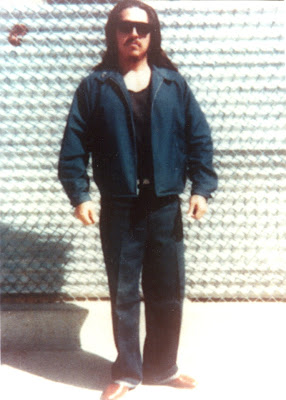

Douglas Ray ‘Chief’ Stankewitz is the longest tenured inmate on California’s death row. Image from freechief.org.

Douglas Ray ‘Chief’ Stankewitz

All this brings me to an Indian I want you to know better than his jury did — Douglas Ray Stankewitz, the longest tenured inmate on California’s death row. Like most Indians who find themselves in a group of non-Indians, he is currently known as “Chief,” but unlike many Indians, he is proud of the nickname.

The government wants to kill Chief because Theresa Greybeal was shot dead in the course of a robbery by a group of people high on heroin, and there is no question that Chief was one of them. There is a serious question about who pulled the trigger, and juries are reluctant to kill individuals who did not pull the trigger. But as far as his jury knew, Douglas Stankewitz pulled the trigger, and he might have, but we will never know, based on his trial.

Just as you can’t discuss federal Indian policy without recourse to history, it’s hard to understand Douglas Stankewitz and his crimes outside of his historical context, which includes the spectacular destruction of California Indians.

Douglas Ray “Chief” Stankewitz is a citizen of the Big Sandy Rancheria, as they call reservations in California. He was born on May 31, 1958, to Marion Sample Stankewitz, the sixth of her eleven children. She was the fifth of seven children. Her father, Sam Jack Sample, was Mono and Chukchansi, and her mother was Mono. She met Douglas’s father, a truck driver of Polish descent, when she was picking grapes and he was her supervisor. They were both practicing drunks.

Douglas was born the year the Big Sandy Rancheria was terminated as part of the national policy to force Indians to assimilate. In other words, for most of the time that the young Douglas was being let down by the adults around him, the Big Sandy Rancheria did not exist in the eyes of the federal government.

His mother had also been raised on the Big Sandy Rancheria, a place until recently blighted by poverty, alcohol abuse, and hopelessness. Marion drank beer by the case while pregnant, and when Douglas was born his father was in jail for beating his mother. His mother had no prenatal care — she first saw a doctor regarding her pregnancy when she was in labor.

Douglas was beaten regularly by both of his parents and was taken to the emergency room three times before his first birthday. At age six, he was found injured and wandering on the streets. The police took him home, where his mother admitted to having beaten him. The police did not remove him from the home, apparently because they decided that the process would have been too complicated. There were nine children in the home at the time, and Douglas’s father was in jail.

Less than three months later, Douglas was brought to the police station by a neighbor who found the boy on his doorstep, again injured. This time, all the children were taken away and Marion was jailed.

After two unsuccessful foster home placements — the foster parents were unable to deal with Douglas’s violent emotional eruptions — the seven-year-old was committed to Napa State Psychiatric Hospital for 90 days. While he received no treatment there (beyond being diagnosed with a severe emotional disturbance), this placement was extended twice, for a total of nine months. This child trapped in an adult institution became easy prey for sexual assault, and that became an unfortunate part of his “education.”

He was then placed in a foster home, where he stayed for nearly four years, the second longest stay at one address he has had in his life. The longest was in is his current address: San Quentin’s death row. He received no visits from his natural family during that placement with the foster family. His foster mother had to make a personal plea to get Douglas into the third grade:

The day I went to pick him up, I’ll never forget. He went down on all fours in a corner, growling and snorting at me. On the way home, he jumped over into the back seat and clawed all the stuffing out of the upholstery. When we walked into the kitchen of my home, he shuffled over to the dish rack, full of dry dishes, and threw the whole thing across the room.

I had been told not to physically restrain or punish him because he would go berserk if touched, but I figured he was already berserk, so being as big as I am, I just grabbed him from behind, wrapped my whole self around him, down we went and I just held on for dear life until he calmed down.

It’s taken me all this time to tame him. I’ve taught him to talk instead of grunt, to use the toilet, to dress himself, to use silverware, to take care of animals without hurting them, to ask instead of grab… He’s been begging me to teach him to read and write and do numbers like the other foster kids, so I think he’s ready for school… Will you take him in your class? If he’s any trouble, just call and I’ll come pick him up.

It is unclear how this foster placement ended, and Chief is in no position to know because of his age at the time. Apparently, the state was motivated by a bureaucratic imperative to keep families together when possible, regardless of the circumstances. What is clear is that from 1970 until his first commitment to the California Youth Authority in 1972, Douglas had at least 13 placements. The longest was for five months. The first was back with his mother, where he learned to sniff paint.

For a short period, he was placed with an aunt back on the reservation, where he lived until her children were taken away because of her drunkenness. The aunt said that before Douglas came to live with her, “a lot of times there was no food in the house. Sometimes we’d save our oatmeal for [the children] because they had nothing.” While Douglas was living with his aunt, his mother was sent to prison for manslaughter.

At age 13, Douglas got his first criminal referral to juvenile court. His earlier visits to juvenile court had been as what the state called a “child in need of supervision.” Douglas had apparently been running with some adults, and when they showed up too late to get fed at a Fresno soup kitchen one day, the adults decided to rob someone to get money for food. Douglas involved himself in this crime by going though the victim’s pockets.

Between 1972 and 1977, Douglas spent all but eight months in either Youth Authority lockups or the Sacramento County Jail. In a little over two months from the time he was released until the arrest that landed him on death row, Douglas Stankewitz consumed (according to the individuals around him) massive quantities of marijuana, alcohol, methamphetamine, and heroin. At the time of the killing that brought him to death row, he had not slept for at least two days.

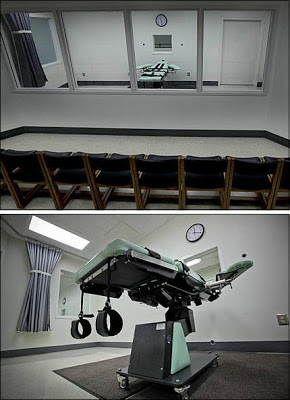

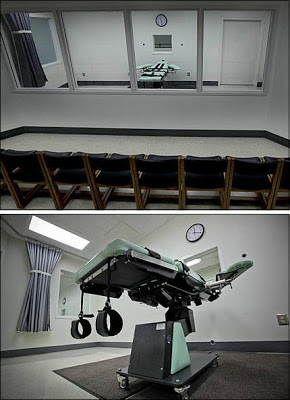

End of the line: Sleek new death chamber at San Quentin. Image from Inland News Today.

The fearsome responsibility

Chief has now spent 33 years of his life on California’s death row, but virtually all of his life before arriving there was spent under the “supervision” of the state of California in one guise or another. We don’t know what the jury on his trial would have made of this, but we do know that Chief’s American Indian identity made their decision to kill him inevitable. That statement may seem shocking, but so are the actions of Douglas Stankewitz’s court-appointed lawyer, the ex-judge Hugh Goodwin.

Since I am a retired judge and know something of the work, I was prepared to think an ex-judge from a criminal court might make a good defense attorney in a capital case, if he had the stomach for it. The problem is that Goodwin became an ex-judge because of his predilection for sentencing criminal defendants to go to church. He was convinced that his job as a judge was to bring people to Jesus. It is clear from reviewing the Stankewitz case that he saw his duty as a criminal defense lawyer the same way.

The fearsome responsibility of a capital defense can keep a lawyer awake at night, but Mr. Goodwin’s sleep was apparently less troubled than mine, because he took the attitude that his client’s life was in God’s hands rather than his own.

Because there was no question that his client was involved in the killing — only whether he pulled the trigger — Mr. Goodwin had ample notice that the main business of this trial would be in the penalty phase. There was much that the jury should have been told in the penalty phase, but Mr. Goodwin did not deem it important to inform them that his client had been born with fetal alcohol syndrome, beaten, starved, sexually assaulted, and deprived of any loving relationship with an adult.

Instead, he called to the stand a jailer and an assistant district attorney to give their opinions that anybody can reform if they allow the Christian God to come into their life. Predictably, the cross-examination of these witnesses bored in on whether they had any reason to believe Douglas Stankewitz had invited God into his life. They did not.

Errors by a lawyer do not require reversal if the lawyer had a tactical reason for making the errors. Hugh Goodwin swore to this statement about his tactics in that trial:

I have never believed in the separation of church and state, as I made clear when I was a judge. I recognize that this is a controversial view which is not widely shared. When I presented the testimony of a Deputy District Attorney and the Fresno County Jail chaplain that they believed people could be transformed by the power of God if they let God into their lives, I knew that it was likely that on cross-examination they would state that there was no evidence that Mr. Stankewitz would let God into his life. Nonetheless, I believed that by presenting this testimony, God’s will would be done, and accordingly I did so.

As idiotic as the “power of God” defense was in a capital murder case, it would have had a prayer of swaying a jury against death if there were a shred of evidence that Douglas Stankewitz had a Christian bone in his body. But Douglas “Chief” Stankewitz is a Mono Indian, born on the Big Sandy Rancheria, raised by the State of California in a parade of incompetent foster homes, mental hospitals and juvenile facilities. His grandfather, Sam Jack Sample, was a ceremonial singer and medicine man who died singing in the roundhouse when Douglas was a small boy. Goodwin might as well have entrusted his client’s life to Zoroaster for all the chance his client had of grabbing hold of that lifeline.

The defense in a capital case must compel the jury to understand the life they are being asked to end. In this case, the jury was told that goodness is linked to being Christian, and the defense lawyer might as well have said plainly that the only good Indians he ever saw were dead.

At this writing, the Big Sandy Rancheria has regained federal recognition and has opened a casino. Using those casino funds, they finally have an office to enforce the Indian Child Welfare Act; they also have a Head Start program.

In another case of poor timing, the name of Sam Jack Sample, Douglas’s grandfather, has turned up on the list of persons for whom the Department of the Interior is holding property in trust. Since Stankewitz’s mother is deceased, he may actually inherit that property, thereby acquiring the funds to pay for his funeral—if he had anyone to attend it.

Chief Stankewitz has no execution date set and the litigation to get him a new trial continues. Until he does get a fair trial, we won’t have any basis to say whether he is among the worst of the worst who deserve the death penalty or whether he is just another man without the capital getting the punishment.

[Steve Russell, Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, lives in Sun City, Texas, near Austin. He is a Texas trial court judge by assignment and associate professor emeritus of criminal justice at Indiana University-Bloomington. Steve was an activist in Austin in the Sixties and Seventies, and wrote for Austin’s underground paper, The Rag. Steve is also a columnist for Indian Country Today, where this article first appeared. He can be reached at swrussel@indiana.edu. Read more articles by Steve Russell on The Rag Blog.]

The Rag Blog