Writ in stone? Image from RalphMag.Zombie-Marxism II:

What Marx got right

Why Marxism has failed, and

why Zombie-Marxism cannot die

(Or, ‘My rocky relationship with Grampa Karl’)

By Alex Knight / The Rag Blog / November 16, 2010

This is the second part of an essay critiquing the philosophy of Karl Marx for its relevance to 21st century anti-capitalism. The main thrust of the essay is to encourage living common-sense radicalism, as opposed to the automatic reproduction of zombie ideas which have lost connection to current reality.

Karl Marx was no prophet. But neither can we reject him. We have to go beyond him, and bring him with us. I believe it is only on such a basis, with a critical appraisal of Marx, that the Left can become ideologically relevant to today’s rapidly evolving political circumstances. Go here for Part I of this series.

What Marx got right

Boiling down all of Karl Marx’s writings into a handful of key contributions is fated to produce an incomplete list, but here are the five that immediately come to my mind: 1. Class Analysis, 2. Base and Superstructure, 3. Alienation of Labor, 4. Need for Growth, Inevitability of Crisis, and 5. A Counter-Hegemonic Worldview.

(It must be noted that many of these insights were not the unique inspiration of Marx’s brain, but were ideas bubbling up in the European working class movements of the 18th and 19th centuries, which was the political context that educated Marx. Further, Marx’s lifelong collaborator, Friedrich Engels, undoubtedly contributed significantly to Marx’s ideas, although Marx remained the primary theorist.)

1. Class analysis

In the opening lines of the Communist Manifesto (1848), Marx thunders, “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.”

In other words, as long as society has been divided into rich and poor, ruler and enslaved, oppressor and oppressed, capitalist and worker, there have been relentless efforts amongst the powerful to maintain and increase their power, and correspondingly, constant struggles from the poor and oppressed to escape their bondage.

This insight appears to be common sense, but it is systematically hidden from mainstream society. People do not choose to be poor or oppressed, although the rich would like us to believe otherwise. The powerless are kept that way by those in power. And they are struggling to end that poverty and oppression, to the best of their individual and collective ability.

The Manifesto elaborates Marx’s class framework under capitalism:

“Our epoch… possesses this distinctive feature: it has simplified class antagonisms: Society as a whole is more and more splitting up into two great hostile camps…: Bourgeoisie and Proletariat” (Marx-Engels Reader, 474).

Marx relayed the words “bourgeoisie” and “proletariat” directly from the French working class movement he encountered in his 1844 exile in Paris, when he briefly ran with the likes of “anarchist” theorist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. Marx himself reminds us, “No credit is due to me for discovering the existence of classes in modern society or the struggle between them.” Class analysis pre-dated Marx by many decades. Yet he articulated the class divisions of capitalist society quite clearly.

The “bourgeoisie” are those who own and control the “means of production,” or basically, the land, factories and machines that make up the economy. Today we know them as the Donald Trumps, the Warren Buffets, etc., although most of the ruling class tries to avoid public scrutiny. In short, the ruling class in capitalism are the wealthy elite, who exert control over society (and government) through their dollars.

Opposing them is the “proletariat,” which Marx defines as “the modern working class — a class of labourers who live only so long as they find work, and who find work only so long as their labour increases capital” (479). The working class for Marx is everybody who has to work for a wage and sell their labor in order to survive.

The divide between the bourgeoisie and proletariat as seen by Marx impacts society in deep and rarely understood ways. However, it is clear that as the rich rule society, they design it for their own benefit through politics, the media, the school system, etc. Inevitably, through “trickle up” economics, the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. As the class conflict worsens, for Marx there can only be one solution — revolution:

“This revolution is necessary not only because the ruling class cannot be overthrown in any other way, but also because the class overthrowing it can only in a revolution succeed in ridding itself of all the muck of ages and become fitted to found society anew” (193, The German Ideology, 1845).

How could it happen? Marx rightly answers, “the emancipation of the working classes must be conquered by the working classes themselves.”

This proclamation comes from the Preamble (1864) of the International Workingmen’s Association, also known as the First International. The International, which Marx helped found, was an organization made up of workers and their allies from across Europe, and a few from outside it.

The International’s goal was the solidarity of workers across national boundaries, becoming united and empowered to lay siege to the capitalist system. Through “class consciousness,” the workers would become aware of their “historic mission,” and through organization, they would build the means to accomplish it.

The key is that Marx believed that change would come from below. It was impossible to decree communism from above. This explains Marx’s slogan, still just as relevant today if not for the gendered language, “Working men of all countries, Unite!”

Today, workers in China are perhaps the most successful practitioners of Marx’s class analysis. As China has opened itself up to Western corporations to take advantage of extremely low wages, China over the last 20 years has transformed itself into the sweatshop of the world. Workers make just a few cents per hour, work up to 12-15 hours per day, and are often forbidden from taking bathroom breaks.

With literally nothing to lose, class struggle must appear to be a viable option for these exploited millions. And they have seized the opportunity. Organizing independently of the Communist Party’s official labor union, Chinese workers have self-organized thousands of massive strikes in the past few years.

In the words of Johann Hari, “Wildcat unions have sprung up, organized by text message, demanding higher wages, a humane work environment, and the right to organize freely. Millions of young workers across the country are blockading their factories and chanting ‘there are no human rights here!’ and ‘we want freedom!’”

What if working men and women of the United States were to join in solidarity with the Chinese workers currently rebelling against totalitarian abuse? What if the primary consuming nation and the primary producing nation had to contend with a united, powerful anti-capitalist movement? It could create a force with the power to bring the entire capitalist system to its knees.

2. Base and superstructure

“High on my own list of Marx’s important insights was the understanding that economics cannot be separated from politics.” – Roger Baker, “Is Marx Still Relevant?“

Marx locates economics as the motive force of history. Marx called this the “materialist conception of history,” as opposed to the idealist conception of history as articulated by the earlier German philosopher, G.W.F. Hegel. Marx, who had been a member of the “Young Hegelians” while attending university, famously “stood Hegel on his head.” Instead of the material world being an extension of the ideas in people’s heads, Marx saw ideas as reflections of material reality, chiefly the economic “relations of production.”

History, for Marx, can best be explained in the context of the evolution and development of human economy. In an early letter (1846), he explains:

“Assume a particular state of development in the productive faculties of man and you will get a particular form of commerce and consumption. Assume particular stages of development in production, commerce and consumption and you will have a corresponding social constitution, a corresponding organisation of the family, of orders or of classes, in a word, a corresponding civil society” (Marx-Engels Reader, 136-7).

Marx therefore separates the economic “base” (or “foundation”) from a social, political, and ideological “superstructure” built on top of it. He elaborated this more fully in A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859):

“The totality of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which arises a legal and political superstructure, and to which correspond definite forms of consciousness. The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political, and intellectual life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness.”

Debates over the extent of Marx’s economic determinism have raged since his death, but Engels clarified his and Marx’s framework in an 1890 letter:

“According to the materialist conception of history, the ultimately determining element in history is the production and reproduction of real life. More than this neither Marx nor I have ever asserted. Hence if somebody twists this into saying that the economic element is the only determining one, he transforms that proposition into a meaningless, abstract, senseless phrase.

The economic situation is the basis, but the various elements of the superstructure: political forms of the class struggle and its results, to wit: constitutions established by the victorious class after a successful battle, etc., juridical forms, and then even the reflexes of all these actual struggles in the brains of the participants, political, juristic, philosophical theories, religious views and their further development into systems of dogmas, also exercise their influence upon the course of the historical struggles and in many cases preponderate in determining their form…

We make our history ourselves, but, in the first place, under very definite assumptions and conditions [emphasis added]. Among these the economic ones are ultimately decisive. But the political ones, etc., and indeed even the traditions which haunt human minds also play a part, although not the decisive one” (Marx-Engels Reader, 760-2).1

The core of Marx and Engels’ argument appears self-evident. Agricultural societies worship crop-related gods, and create social structures such that divide people into Lord and peasant. Industrial societies worship technology and money, and create classes such as financier and worker. What good would it have done for an Egyptian pharaoh to attempt to create something like the Internet, if the economic means (microchips, factories, wage labor, international banking) didn’t exist? Or, more precisely, how would the pharaoh have conceived of the Internet without these material conditions existing in front of him?

The concept of base and superstructure has many useful applications. For example, Marx articulated in his essay “The German Ideology,” that those in power materially can also exert ideological control over the rest of society. “The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas, i.e. the class which is the ruling material force of society, is at the same time its ruling intellectual force” (M-ER, 172). Today we know this as propaganda and brainwashing.

Building off these ideas, later Marxists such as Antonio Gramsci developed a critique of “hegemony” — the dominance of one group of people, or one ideology, based on consent and persuasion, rather than by brute force. In other words, hegemony means the oppressed accept their oppression, internalizing and perhaps even outwardly arguing for the mythology of their rulers. People are much easier to rule if they believe it is for their own good.

Hegemony is a highly relevant idea to our situation today, especially in the United States where the population is thoroughly indoctrinated with the mythology of capitalism — seeing the system as positive and liberating, rather than violent and destructive as it actually is.

However, if the base of the American economy continues to deteriorate as it has, Marx would suggest the superstructure is sure to follow, and revolutionary change is perhaps not far around the corner.

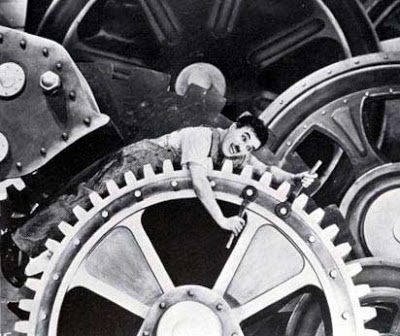

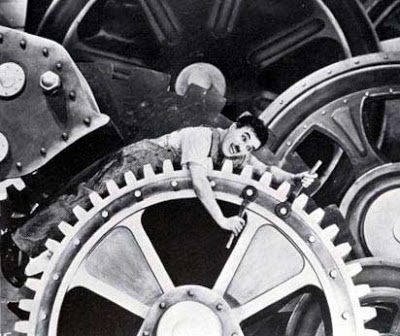

Alienated labor? Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times.

3. Alienation of labor

At the core of Karl Marx’s extensive critique of capitalism is his critique of the alienation of labor.

Marx used to spend weeks on end at the library, thoroughly researching the findings of the major economic theorists of capitalism. One of his important discoveries was Adam Smith’s “labor theory of value,” which posits that the value of a commodity is proportional to the quantity of human labor used to create it. A highly complex product, such as a space shuttle, is valuable (or expensive) in part because of the thousands of work-hours spent by hundreds of workers in the construction of its parts and their assembly. Whereas constructing a wheel-barrow is significantly less labor-intensive, it is therefore worth less money.

Marx extrapolated from this theory, showing that because labor produces everything of value (along with what nature provides), the entire system of capitalist accumulation is sustained by profiting off the backs of workers.

The focal argument of Capital, Volume 1 (1867), is that there would be no capital if not for the exploitation of labor. Marx coins the phrase “surplus value” to show that workers produce a higher value of goods for their bosses than they receive for themselves in wages. In effect, the worker only gets paid for working half a day, which is the amount of pay needed to keep him or her alive, yet he or she works a full day. What they produce in the second half of the day is therefore pure profit for their employer. “The rate of surplus-value is an exact expression for the degree of exploitation of labour-power by capital, or of the labourer by the capitalist” (Chapter IX).

Marx hereby creates the fascinating distinction between the worker’s “living labor,” and the machines, commodities and wealth (capital) created by that living labor, called “accumulated labor” or “dead labor.” While the worker produces surplus value for capital, giving the capitalist an incentive to keep the worker hard at work, the worker’s life diminishes in direct proportion to the work performed. This exploitation is the basis of the entire system: “[W]hat is the growth of productive capital? Growth of the power of accumulated labour over living labour. Growth of the domination of the bourgeoisie over the working class” (Marx-Engels Reader, 210).

I believe “Alienated Labour,” written as part of the “Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844,” is Marx’s most enduring and relevant essay. It originally went unpublished and was only re-discovered in the 20th century, influencing the “New Left” of the 1960s, which was largely concerned with the pervasive alienation of modern consumer capitalism.

In the essay, Marx elaborates on the distinction between the worker’s active labor and the product of his or her labor:

“The worker becomes all the poorer the more wealth he produces, the more his production increases in power and range. The worker becomes an ever cheaper commodity the more commodities he creates. With the increasing value of the world of things proceeds in direct proportion the devaluation of the world of men. Labor produces not only commodities; it produces itself and the worker as a commodity” (M-ER, 71).

The alienation of labor therefore emerges from the reality that under capitalism, human beings are reduced to commodities, whose value is expressed through wage labor. For most of us, survival is impossible without pimping ourselves out to the highest bidding employer. Unfortunately, when we sell ourselves for a wage, we also give up power over what we do with our time. What we produce is not under our control or discretion. Our work activity and its product are therefore alien to us.

“[T]he worker is related to the product of his labor as to an alien object. For on this premise it is clear that the more the worker spends himself, the more powerful becomes the alien world of objects which he creates over-against himself, the poorer he himself — his inner world — becomes, the less belongs to him as his own” (72).

Because the wage workers are disempowered in the process of work, their labor gives birth not to a world in their own, human, image but to a world in the image of capital. It is an alien world, full of meaningless commodities, but very little humanity. Humanity has been conscripted into the wage labor process, against its will. Workers themselves are ever being produced, as humans who have lost touch with their “intrinsic nature.”

The essay’s climax is prompted by Marx’s question, “What, then, constitutes the alienation of labor?”

“First, the fact that labor is external to the worker, i.e., it does not belong to his intrinsic nature; that in his work, therefore, he does not affirm himself but denies himself, does not feel content but unhappy, does not develop freely his physical and mental energy but mortifies his body and ruins his mind.

The worker therefore only feels himself outside his work, and in his work feels outside himself… His labor is therefore not voluntary, but coerced; it is forced labor. It is therefore not the satisfaction of a need; it is merely a means to satisfy needs external to it. Its alien character emerges clearly in the fact that as soon as no physical or other compulsion exists, labor is shunned like the plague…

Lastly, the external character of labor for the worker appears in the fact that it is not his own, but someone else’s, that it does not belong to him, that in it he belongs, not to himself, but to another… As a result, therefore, man (the worker) only feels himself freely active in his animal functions — eating, drinking, procreating, or at most in his dwelling and in dressing-up, etc.; and in his human functions he no longer feels himself to be anything but an animal” (74).

This is Marx at his most human, and therefore his most relevant. This passage resonates because it speaks directly to our concrete needs, which are not only economic, but mental, emotional, and spiritual. Marx is articulating something core here — the work we do for our bosses creates their profits, but it makes us miserable in the process.

We create commodities and services which are not our own, which are not designed for our concrete needs but based solely on the demands of the market, and as a result, we are alienated from our own humanity. If we did not need wages to survive, we could just as easily quit our worthless, meaningless jobs. Unfortunately, the joke is on us. With each hour of work that deadens our souls, we give more life and power to the very “alien world of objects” that oppresses us.2

The phrase “Work sucks” therefore becomes literal. Our lives are sucked out of us by the vampire of capital.

4. Need for growth, inevitability of crisis

Why does work have to suck in a capitalist society? For the simple reason of the profit motive. By exploiting workers, the system creates profit, and therefore grows. Growth is capitalism’s raison d’etre — reason for being. Without growth, capitalism would wither and die.

In Capital Volume 1, Marx lays out his “General Formula of Capital”: M—C—M’. M=money, C=commodities, M’=more money (Marx Engels Reader, 336).

The formula indicates that on the micro level, capital is nothing but the movement of money into a larger amount of money, producing profit. Marx explains this endless movement of money as the inner workings of the system:

“Value… becomes value in process, money in process, and, as such, capital. It comes out of circulation, enters into it again, preserves and multiplies itself within its circuit, comes back out of it with expanded bulk, and begins the same round ever afresh” (335).

Thus, capital is like a shark — it must keep moving in order to breathe. If it were to sit still, it would quickly suffocate. Only by constantly finding and exploiting investment opportunities can capital accumulate, and thereby, survive. This ever-present need to grow therefore compels each individual capitalist to maximize profit.

“The expansion of value, which is the objective basis or main-spring of the circulation M—C—M, becomes [the capitalist’s] subjective aim, and it is only in so far as the appropriation of ever more and more wealth in the abstract becomes the sole motive of his operations, that he functions as a capitalist, that is, as capital personified and endowed with consciousness and a will (emphasis added)… The restless never-ending process of profit-making alone is what he aims at.” (334).

Here Marx explains that capital’s need for growth determines the actions of each individual capitalist, such as a wealthy financier, or the modern example, a multinational corporation. In Marx’s brilliant language we can therefore understand Wal-Mart or Sony as “capital personified.” Their one and only motive is to profit, to grow. All other considerations, ecological or social, are essentially irrelevant.

Suppose a capitalist/corporation failed to create growth, either mistakenly, or somehow purposely abdicated their role in the system. What would happen? Very simply, capital would work its way around them. Another capitalist would come along, a competitor, to take advantage of the situation, and inevitably put the first capitalist out of business. Marx names this competition between capitalists “the industrial battlefield.”3

This war of competition makes it impossible to simply blame BP, British Petroleum, for its shoddy safety standards which led to the poisoning of the Gulf. If BP prioritized safety over profit, the company would lose a competitive edge to its rivals, Exxon-Mobil or Chevron-Texaco. It is only by obeying the command of capital to constantly grow or die, that a capitalist survives. The entire system must be indicted — “hate the game, not the player.”

As each capitalist serves his master and performs the ritual of profit-making, the system as a whole also necessarily expands “on an ever more gigantic scale” (214). This systemic expansion is famously described in the Communist Manifesto:

“The need for a constantly expanding market for its products chases the bourgeoisie over the whole surface of the globe. It must nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connexions everywhere… The cheap prices of its commodities are the heavy artillery with which it batters down all Chinese walls… It compels all nations, on pain of extinction, to adopt the bourgeois mode of production.” (476-7).

As each capitalist battles for resources, labor, and markets for its goods, every community, every nation, and eventually the entire planet itself, is consumed. Capital therefore creates a global system, organized by the incessant requirement of accumulation. The entire system must grow.

Should capitalism ever cease growing, a crisis would necessarily develop. Investors would cease making investments for fear that they would not get a return. Businesses would cut back, laying off workers, which has the effect of reducing consumer demand. Without a friendly investment environment, things can rapidly enter a downward spiral. And as Marx emphasized, this happens over and over again, through “the commercial crises that by their periodical return put on its trial, each time more threateningly, the existence of the entire bourgeois society” (478).

As Marxist professor David Harvey likes to quote, Marx states in the “Grundrisse” (1857) that capital cannot “abide” limits. Any limit which would stand in the system’s path must be transcended or circumvented in some way to keep the accumulation of capital alive and well. Can this accumulation continue forever? Clearly it cannot. Because we live on a finite planet, the idea of an ever-increasing system of production and consumption is absurd on its face. At some point the limits to growth will be reached.

Marx seemed to sense these limits instinctively in “Wage Labour and Capital” (1847):

“Finally, as the capitalists are compelled… to exploit the already existing gigantic means of production on a larger scale and to set in motion all the mainsprings of credit to this end, there is a corresponding increase in industrial earthquakes… [Crises] become more frequent and more violent, if only because, as the mass of production, and consequently the need for extended markets, grows, the world market becomes more and more contracted, fewer and fewer markets remain available for exploitation (emphasis added), since every preceding crisis has subjected to world trade a market hitherto unconquered or only superficially exploited” (217).

When will capitalism hit the limits to growth? The answer is, in my opinion, quite soon. As David Harvey states dispassionately, “There are abundant signs that capital accumulation is at an historical inflexion point where sustaining a compound rate of growth is becoming increasingly problematic.”

Speaking directly to this question, I propose the End of Capitalism Theory to suggest that at this moment in history, no great new sources of wealth remain to be conquered. We are near or at the global peak of oil production, and the planet is having increased difficulty sustaining the ecological damage produced by capitalist production and waste.

These ecological limits are joined by the social limits to growth, manifest in people’s resistance to capitalism all over the world. The aforementioned Chinese workers’ movement is only the most dramatic example. From Bolivia to Greece to the schools of California, more and more people are rejecting the alienating and dehumanizing roles that capitalism forces them into, and by standing up for themselves are placing limits on the ability of the system to increase its power over them — to grow.

It is natural to try to make sense of the extremely broad and deep crisis we are living through. As the crisis has dragged on over the last few years, sales of Marx’s Capital have skyrocketed. I suspect people are looking for an explanation for why capitalism has failed. The End of Capitalism Theory is one attempt at an explanation. I encourage others to come forward.

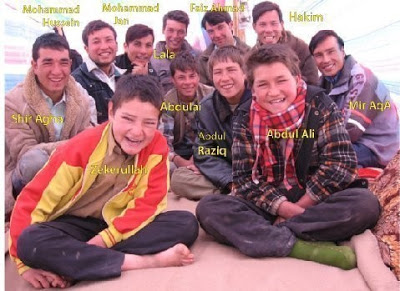

Chinese workers in Guangdong, 2006. Image from Ensaios Imperfeitos.

5. A counter-hegemonic worldview

The name of Karl Marx endures to this day as virtually synonymous with anti-capitalism. In contrast to the hegemonic world-view of capitalism, which sees itself as essentially a meritocracy where people are rewarded for hard work and receive what they deserve, Marx outlined a theory of capitalism that was grounded in exploitation and destruction. This critique formed the basis of an entirely new narrative, a new story about ourselves and our world.

While the core elements of Marx’s narrative were largely spelled out by the working class movement of Europe he immersed himself in, Marx was the transcriber. He put the story of European workers on paper, and adding his own philosophical learnings, deepened and elaborated the story so that these workers’ struggle became emblematic of the dilemma of capitalist development as a whole.

Marx’s “scientific socialism” was distinguished from the approach of other European socialists by his reaching for the big picture. It wasn’t enough to criticize capitalism, Marx felt it was necessary to describe, with as much precision as possible, the conditions that enabled it to exist and which would enable its destruction. In so doing, Marx constructed a counter-hegemonic world-view, a way of seeing the world which was complete enough in itself that it could seriously rival the dominant capitalist explanation of reality.

I want to highlight three aspects of Marx’s world-view that make it so enduring. First, his story gives us meaning and a place in history. Second, it gives us direction and purpose. Third, it is brilliantly told, with poetic and even mystical language weaved alongside the densest of political economic writing.

Every good story reveals to us something about ourselves. The really great stories — the ones which captivate people for centuries or even millennia — are the ones that provide answers to life’s most fundamental questions: “Who are we?” and “Why are we here?”

Marx’s philosophical education with the Young Hegelians gave him the drive to search for answers to these fundamental questions, as well as the critical tools to deconstruct the popular narratives of the day. He pursued fellow German philosopher Feuerbach in discarding the Christian narrative that predominated in his time, asserting that God was not the creator of humanity, but rather that the inverse was true. Humanity had created God, projecting him into the heavens from our own hopes and fears.

“In direct contrast to German philosophy which descends from heaven to earth, here we ascend from earth to heaven. That is to say, we do not set out from what men say, imagine, conceive, nor from men as narrated, thought of, imagined, conceived, in order to arrive at men in the flesh. We set out from real, active men, and on the basis of their real life-process we demonstrate the development of the ideological reflexes and echoes of this life-process… Life is not determined by consciousness, but consciousness by life” (Marx-Engels Reader, 154-5, “The German Ideology”).

For Marx, then, we lead our own lives as earthly beings. However, we do not start with a blank slate, because we are also historical beings, the inheritors of the past. This past is brought down to us not only in terms of stories and myths, but especially in terms of material activity.

“History is nothing but the succession of the separate generations, each of which exploits the materials, the capital funds, the productive forces handed down to it by all preceding generations, and thus, on the one hand, continues the traditional activity in completely changed circumstances and, on the other, modifies the old circumstances with a completely changed activity” (172).

Who we are, according to Marx, is the descendants of thousands of generations of human-kind and the care-takers of that living legacy, which for Marx is especially an economic (or “productive”) legacy.4 What can be accomplished by the current generation is necessarily a function of the machines, tools, social structures, etc. that our ancestors leave us.

Marx adds an interesting plot-twist when he specifies that in this era of capitalism we are living in unique circumstances which distinguish our present era from all human history. From the “Communist Manifesto”:

“The bourgeoisie, during its rule of scarce one hundred years, has created more massive and more colossal productive forces than have all preceding generations together. Subjection of Nature’s forces to man, machinery, application of chemistry to industry and agriculture, steam-navigation, railways, electric telegraphs, clearing of whole continents for cultivation, canalisation of rivers, whole populations conjured out of the ground — what earlier century had even a presentiment that such productive forces slumbered in the lap of social labour?” (477).

Given that our generation sits atop this dramatic expansion of ‘productive forces,’ it now falls to us to decide what to do with such historic power. Marx makes clear that we have a special responsibility to fulfill.

“In the earlier epochs of history, we find almost everywhere a complicated arrangement of society into various orders, a manifold gradation of social rank. In ancient Rome we have patricians, knights, plebeians, slaves; in the Middle Ages, feudal lords, vassals, guild-masters, journeymen, apprentices, serfs… The modern bourgeois society that has sprouted from the ruins of feudal society has not done away with class antagonisms. It has but established new classes, new conditions of oppression, new forms of struggle in place of the old ones” (474, “Communist Manifesto”).

Our capitalist era is special not only because of the massive growth of the economy, but also because of the unique and unparalleled class inequality between “bourgeoisie” and “proletariat.” In particular, the proletarians are the protagonists of Marx’s story, who carry within them the seed of a new world.

“A class is called forth, which has to bear all the burdens of society without enjoying its advantages, which, ousted from society, is forced into the most decided antagonism to all other classes; a class which forms the majority of all members of society, and from which emanates the consciousness of the necessity of a fundamental revolution, the communist consciousness” (192-3, “The German Ideology”).

Marx assigns the proletarians the role of liberating not only themselves as a class, but of putting an end to class as such. This is accomplished first through the “ever-expanding union of the workers,” who wage an economic struggle against the capitalists and build their power, and finally through communist revolution. According to Marx, this revolution fulfills the proletarians’ “historic role.”

“[The communist revolution] does away with labour, and abolishes the rule of all classes with the classes themselves, because it is carried through by the class which no longer counts as a class in society, is not recognised as a class, and is in itself the expression of the dissolution of all classes, nationalities, etc., within present society” (193).

Now the narrative reaches its climax. After thousands of years of bondage, the opportunity to put an end to human oppression once and for all is now approaching. Due to the twin emergence of highly developed “productive forces” which offer the possibility of abolishing “material want,” alongside a massive and desperate proletariat, the conditions are ripe, for the first time, for the final victory of the working class. And if the workers are able to liberate themselves, they will likewise liberate all of humanity.

“In the place of the old bourgeois society, with its classes and class antagonisms, we shall have an association, in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all” (491).

A communist society would be established to provide for each individual, each community, and each nation, to develop themselves freely, rather than being slaves to the market. And this is how Marx’s story ends:

“[Communism] is the solution of the riddle of history and knows itself to be this solution” (Bottomore 155, “Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844″).

The strength of Marx’s narrative is not only that it gives us a meaning that transcends our individual lives to include our common, human, legacy. Nor is limited to providing us with a purpose and mission, so that we can see ourselves as historical actors. The final piece of the puzzle for Marx’s successful story is his poetry, as reflected in passages such as this:

“The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win” (500).

For a writer of philosophy and political economy, which is typically the densest and most technical prose, Marx consistently displays a poetic sensibility. His words often have a beauty and an art; they conjure up images that help the reader appreciate the fantastic nature of the story Marx is weaving. Here is one of his most famous sections from the “Communist Manifesto”:

“Constant revolutionising of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. All fixed, fast-frozen relations… are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses, his real conditions of life” (476).

Much of Marx’s poetry takes the form of dialectics. Dialectics, which formed much of Hegel’s thought and interest, are a way of thinking about contradicting forces opposing one another within a larger whole, whose contradictions transform that larger whole into something different. These transformations occur through “negations,” as opposites overtake one another. Dialectical thought can be traced back to the ancient Greeks, and is embedded in much Eastern philosophy and religion as well. For example, the Yin and Yang of Taoism represents a whole which contains opposites in contradiction.

Marx was fascinated by the complexity of dialectical thought. Turning to a random page, I can pick many passages to display his interest. Here is another from the “Communist Manifesto”:

“In bourgeois society, therefore, the past dominates the present; in Communist society, the present dominates the past. In bourgeois society capital is independent and has individuality, while the living person is dependent and has no individuality” (485).

In this excerpt, Marx expounds two dialectics: the past vs. the present, both of which exist together in the now, and capital vs. the living person, both of which strive for independence.

The darkness and mystery which surround dialectical ideas grab hold of our imagination, making the impossible appear possible. There is a mystical quality to these ideas. Like television, Marx’s writing both disturbs and fascinates — the complexity of thought pushes the reader away at the same time that its dynamism draws them in.

Here is one of Marx’s most brilliant and memorable uses of dialectics, his attack on the division of labor and specialization:

“[A]s long as a cleavage exists between the particular and the common interest, as long, therefore, as activity is not voluntarily, but naturally, divided, man’s own deed becomes an alien power opposed to him, which enslaves him instead of being controlled by him. For as soon as the distribution of labour comes into being, each man has a particular, exclusive sphere of activity, which is forced upon him and from which he cannot escape.

He is a hunter, a fisherman, a shepherd, or a critical critic, and must remain so if he does not want to lose his means of livelihood; while in communist society, where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, shepherd or critic” (160, “The German Ideology”).

Poetry takes Marx’s narrative to its most important destination — the human heart. Readers are drawn in by the language and internalize this story as their own — seeing themselves for the first time in relation to the historic moment in which we live, and the historic mission with which Marx presents us. This power to reach hearts and minds is the reason Marx’s world-view was able to become counter-hegemonic, and actually challenge the capitalist claim on reality.

However, with this power there is also a danger. As reality is ever-changing, a worldview can either continue to develop and remain relevant, or it can become static and outdated by failing to adapt. The very fascination that a narrative wields can also distract its adherents from asking difficult questions that would breathe new life into the framework.

By defending its weaknesses, one facilitates the narrative remaining hegemonic, but saps it of the potential to evolve and incorporate new, critical perspectives. In the short-term, the narrative survives, but in the long-term, it decays.

The Marxist worldview has fallen victim to this very dynamic. As organs of the narrative have lost circulation with reality and gangrened, they have not been amputated, but allowed to persist as parasites on the elements of Marx’s ideas that remain alive.

Yet, responsibility for today’s Zombie-Marxism cannot be placed entirely on the shoulders of his followers; we must trace the origins of this horror back to the misconceptions in Karl Marx’s writings. The next section of the essay will explore those misconceptions.

Here is an outline of the entire essay. Check back soon for more!

* Introduction

* My Encounter with Grampa Karl

* What Marx Got Right

- Class Analysis

- Base and Superstructure

- Alienation of Labor

- Need for Growth, Inevitability of Crisis

- A Counter-Hegemonic World-view

*What Marx Got Wrong

- Linear March of History

- Europe as Liberator

- Mysticism of the Proletariat

- The State

- A Secular Dogma

* Hegemony over the Left

* Zombie-Marxism and its Discontents

* Conclusion: Beyond Marx, But Not Without Him

Footnotes

1. Engels adds this interesting note to the discussion of economic determinism: “Marx and I are ourselves partly to blame for the fact that the younger people sometimes lay more stress on the economic side than is due to it. We had to emphasise the main principles vis-a-vis our adversaries, who denied it, and we had not always the time, the place or the opportunity to allow the other elements involved in the interaction to come into their rights… And I cannot exempt many of the more recent ‘Marxists’ from this reproach, for the most amazing rubbish has been produced in this quarter, too” (Marx-Engels Reader, 760-2).

2. In “Wage Labour and Capital” (a speech delivered to German workers in 1847), Marx brilliantly expanded on the alienation of labor in terms of the division of labor caused by the development of machine industry. “The greater division of labour enables one worker to do the work of five, ten, or twenty; it therefore multiplies competition among the workers fivefold, tenfold and twentyfold. The workers do not only compete by one selling himself cheaper than another; they compete by one doing the work of five, ten, twenty… Further, as the division of labour increases, labour is simplified. The special skill of the worker becomes worthless. He becomes transformed into a simple, monotonous productive force… His labour becomes a labour that anyone can perform. Hence, competitors crowd upon him on all sides, and besides we remind the reader that the more simple and easily learned the labour is, the lower the cost of production needed to master it, the lower do wages sink, for, like the price of every other commodity, they are determined by the cost of production.

Therefore, as labour becomes more unsatisfying, more repulsive, competition increases and wages decrease. The worker tries to keep up the amount of his wages by working more, whether by working longer hours or by producing more in one hour. Driven by want, therefore, he still further increases the evil effects of the division of labour. The result is that the more he works the less wages he receives, and for the simple reason that he competes to that extent with his fellow workers, hence makes them into so many competitors who offer themselves on just the same bad terms as he does himself, and therefore, in the last resort he competes with himself, with himself as a member of the working class.” (214-5).

3. Also in “Wage Labour and Capital,” Marx explains the strategy of this “industrial war of the capitalists among themselves”: produce ever-growing quantities of increasingly cheap commodities. “One capitalist can drive another from the field and capture his capital only by selling more cheaply. In order to be able to sell more cheaply without ruining himself, he must produce more cheaply, that is, raise the productive power of labour as much as possible. But the productive power of labour is raised, above all, by a greater division of labour, by a more universal introduction and continual improvement of machinery. The greater the labour army among whom labour is divided, the more gigantic the scale on which machinery is introduced, the more does the cost of production proportionately decrease, the more fruitful is labour [for the capitalist]. Hence, a general rivalry arises among the capitalists to increase the division of labour and machinery and to exploit them on the greatest possible scale.

The more powerful and costly means of production that he has called into life enable him to sell his commodities more cheaply, they compel him, however, at the same time to sell more commodities, to conquer a much larger market for his commodities.” (211-2).

Noting that profit for the capitalists is inversely proportional to the wages paid out to workers, he adds, “this war has the peculiarity that its battles are won less by recruiting than by discharging the army of labour. The generals, the capitalists, compete with one another as to who can discharge the most soldiers of industry” (215).

4. In a similar passage from an 1846 letter to one P.V. Annenkov, Marx explains: “Every succeeding generation finds itself in possession of the productive forces acquired by the previous generation, which serve it as the raw material for new production, a coherence arises in human history (emphasis added), a history of humanity takes shape which is all the more a history of humanity as the productive forces of man” (137).

[Alex Knight is an organizer, teacher, and writer in Philadelphia. He maintains the website endofcapitalism.com and is writing a book called The End of Capitalism. He can be reached at activistalex@gmail.com.]

Also see:

The Rag Blog