Mondragon: Reinventing humanity

It is a striking vision, and a welcome alternative to the dog-eat-dog competition that is rampant both within and between conventional enterprises.

By Bill Meacham / The Rag Blog / October 6, 2011

The human capacity for second-order mentation — the ability we have to consider in thought and imagination not just the world around us but ourselves as well — has led existentialists such as Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone deBeauvoir to say that the human being is always free to recreate himself or herself, that we have no fixed essence, but are what we make of ourselves.

There is certainly a germ of truth in this assertion. If you suffer from some behavioral or psychological problem, the first step in fixing it is to admit that you have a problem; that is, to be conscious enough of yourself to know that there is something you are doing or feeling or thinking that is causing trouble. Then you can mentally step back, reassess the situation, and start doing something different.

In practice, of course, this is often more easily said than done, and there is in fact quite a bit that is fixed about human nature. But within that fixity we have the freedom to reinvent ourselves. By virtue of second-order mentation, we are not fully constrained by the past.

In the individualistic West we tend to think of this freedom in purely personal terms. A young man asks whether he should leave his ailing mother to join the resistance or stay and take care of her, and Sarte’s answer is that the only answer is the young man’s freedom to choose: “You are free, therefore choose, that is to say, invent.”[1] But a more powerful form of self-invention is to be found in the social realm. Case in point: The Mondragon cooperatives.

The Mondragon cooperatives are a federation of worker-owned cooperatives based in the Basque region of Spain. Founded in 1956 through the efforts of a visionary Catholic priest, Father José María Arizmendiarrieta, Mondragon started as a small, worker-owned enterprise making kerosene stoves in 1956. It has since grown to become the seventh-largest business group in Spain, with annual sales of 14 billion Euros and over 100,000 workers. It comprises over 260 affiliated enterprises, including 120 core cooperatives, and has affiliates not just in Europe but around the globe.

The worker-owned cooperative is the core Mondragon social institution and the most ingenious reinvention of what it is to be human. In the cooperative, the workers themselves own the enterprise. There is no outside owner, unlike the capitalist corporation or the communist state-owned collective.

Each worker-owner has one vote, and decisions are made by democratic vote of all owners. Structurally, it is like a sole-proprietorship, except that there are many proprietors, the workers. Nobody gets a wage; instead each is paid a monthly advance on his or her share of the year’s projected profit.

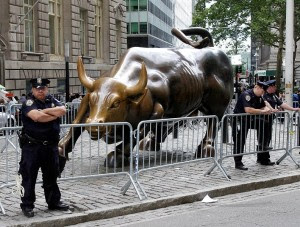

The worker cooperative is a fundamental inversion of the corporate model we take for granted in the capitalist world. In a conventional company, the owners of capital have ultimate authority, and the laborers are subservient. In a worker-owned cooperative, labor has ultimate authority, and capital is subservient, a principle known as Sovereignty of Labor.

What it means in practice is that the workers, being the owners, run the enterprise for their own benefit, not for the benefit of a separate class of people who own it but do not do the work. No outside owner can shut down a factory, fire the workers, and move production somewhere else. No outside owner can mandate overtime, reduced pay, or hazardous working conditions.

The objective is not to make as much profit as possible for a few, but to make a good living for all. And in fact the worker-owners make, on average, 10 percent more than their counterparts in neighboring non-cooperative businesses.

Sovereignty of labor has several implications:

- Democratic control: one worker, one share, one vote.

- Distribution of profits only to workers, the cooperative, or the local community, not to outside investors.

- Egalitarian income spread. On average, the highest-paid worker in a Mondragon enterprise makes four to five times as much as the lowest. The maximum is nine times as much. (Contrast this to many big corporations, whose ratio may be as much as several hundred to one.)

- Participation in decision making. Each cooperative elects its own management team and has an annual meeting at which the worker-owners make strategic decisions about the enterprise. And there is a general council consisting of representatives from all the member cooperatives that makes decisions about the corporation as a whole.

Three things were of crucial importance from the very start: school, credit union, and factory. In 1943, well before the first manufacturing enterprise, Father Arizmendiarrieta started a trade school, so students would have necessary skills to make a living and to form and run a cooperative. He also started a credit union, so people could pool their savings to provide start-up capital. Only when these were in place did the first manufacturing operation begin. A factory alone would lack ongoing sources of credit and new innovative skills.

In addition, the Mondragon cooperatives correct a fatal flaw that has historically led to the demise of worker-owned enterprises. In the Mondragon co-ops, a retiring worker’s share cannot be sold to just anyone, not even another co-op member, but only to a new incoming worker or back to the co-op. This prevents external stock buyers, speculative capitalists, from taking over successful co-ops.

Many an ESOP (Employee Stock Ownership Plan) enterprise has collapsed because shares were sold to non-employees who, after acquiring enough of them, terminated or radically changed the business. In the Mondragon cooperatives, capital and ownership of the business stays with the workers.

Sovereignty of labor is only one of the 10 core principles of the enterprise. The complete list includes such things as a ban on discrimination for religious, political, ethnic, or sexual reasons; democratic and participatory management; cooperation among member co-ops and with other cooperative movements world-wide; and a commitment to social transformation and education.

It is a striking vision, and a welcome alternative to the dog-eat-dog competition that is rampant both within and between conventional enterprises.

Certainly the worker-owners think so. Even if offered more pay somewhere else, most would not leave. They like the job security and the fact that they have a vote. The cooperative meets fundamental human needs: not just the needs for sustenance and social contact, but for self-determination as well.

The cooperative model is promising for a sustainable future, because it is not driven to grow in the same way as the capitalist model and because it allows its worker-owners benefits other than increased material consumption.

Democratically-controlled firms do not have the same drive for growth as capitalist firms. Capitalist firms aim at maximizing total profit, while cooperative firms aim at maximizing profit per worker. If a capitalist firm grows, doubles its workforce and doubles its profit, the owners get richer. If a cooperative firm grows, doubles its workforce and doubles its profit, each worker-owner gets the same amount of money. There is no internal motivation to grow.[2]

There are external motivations to grow, of course. Growth can provide economies of scale, driving costs down. Growth can provide more share of the market, so the firm is more assured of continued operation. The Mondragon cooperatives are enterprises in a market economy, subject to the same constraints and imperatives of competition that capitalist enterprises are.

But there is an important difference. When innovation brings about a productivity gain, worker-owners are free, if they wish, to opt for more leisure or investment in other market opportunities instead of higher pay, which would lead to increased consumption. Reduced consumption makes for reduced environmental impact.

In a world of vast but limited resources, an expanding population and more and more pollution, it is crucial to find ways of satisfying human needs without degrading the environment. Over-consumption — buying stuff we don’t really need – is a threat to the environment because it uses up more resources and produces more waste than necessary.

A capitalist owner would be unlikely to allow workers to work less because they have become more productive. There’s no profit in that. But worker-owners, once they reach a certain level of income, might well opt for such a solution, preferring time with family and friends to the means to buy more goods.[3]

The success of the Mondragon co-ops is undeniable, so it is natural to want to replicate it elsewhere. One wonders how much that success is due to factors unique to the Basque country where it started. Perhaps there is something special about the Basque culture. Mondragon is the best known but not the only cooperative enterprise there. The area is rife with producer co-ops (where farm owners, but not their workers, are members), marketing co-ops, consumer co-ops, transport co-ops, housing co-ops and cooperative schools.[4]

The Basque people have a strong sense of ethnic, linguistic, and cultural identity, and they were an oppressed minority under Franco, leading to an even stronger internal cohesion. They have a tradition of equitable land distribution. The first business produced a much-needed product at a good price; and the area is strategically located, with easy access to large ports like Bilbao, and short distances to major export markets.[5]

Which of these factors is most important for a successful worker’s co-op? Beyond the ability to make and sell a product, which is essential to any economic enterprise, my guess is that in-group cooperation in the face of external hostility had a lot to do with it in the Basque country.

Cooperation, of course, is an inherent human ability and activity. We are most cooperative in the face of an external threat, but we have the ability, in common with our bonobo cousins, to cooperate among groups as well. If we want to replicate Mondragon’s success, we need to foster a sense of empathy, solidarity, and compassion among all humans, a sense that we are all members of one tribe, one family, the human family.

Can we do that? Can we emulate the vision and drive of Father Arizmendiarrieta, without whom the Mondragon co-ops would not have begun? A journalist once remarked that Arizmendiarrieta had created a progressive economic movement anchored in an educational institution. He replied “No, it is just the reverse. We are creating an educational movement for social change, but with anchors in economic institutions.”[6]

It is the whole of humanity that matters most. Perhaps we can form a more cooperative society if we take as our common enemy ignorance, rather than some other group of humans.

Notes

[1] Sarte, Existentialism is a Humanism.

[2] Schweickart, Is Sustainable Capitalism Possible? p. 112.

[3] Idem., p. 113.

[4] Davidson, New Paths to Socialism, p. 26.

[5] Long, The Mondragon Co-operative Federation.

[6] Davidson, New Paths to Socialism, p. 25.

References

Davidson, Carl. New Paths to Socialism: Essays on the Mondragon Cooperatives. Pittsburgh, PA: Changemaker Publications, 2011.

Long, Mike. The Mondragon Co-operative Federation: A Model for our Time? On-line publication, http://www.cooperativeindividualism.org/long_mondragon.html as of 18 September, 2011.

Mondragon Corporation. Corporate website. On-line publication, http://www.mcc.es/ENG.aspx as of 17 September 2011.

Sartre, Jean-Paul. Existentialism is a Humanism. On-line publication, http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/sartre/works/exist/sartre.htm as of 17 September 2011.

Schweickart, David. Is Sustainable Capitalism Possible? In Davidson, New Paths to Socialism, pp. 103 – 126.

Wikipedia. “Mondragon Corporation.” On-line publication, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mondragon_Corporation as of 17 September 2011.

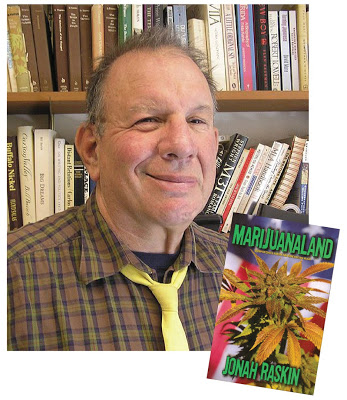

[Bill Meacham is an independent scholar in philosophy. A former staffer at Austin’s 60s underground paper, The Rag, Bill received his Ph.D. in philosophy from the University of Texas at Austin. Meacham spent many years working as a computer programmer, systems analyst, and project manager. He posts at BillMeacham.com, where this article also appears. Read more articles by Bill Meacham on The Rag Blog]

Also:

- Read articles about the Mondragon Corporation by Carl Davidson on The Rag Blog.

- Listen to Thorne Dreyer’s Rag Radio interview with Carl Davidson about Mondragon and the workers’ cooperative movement.