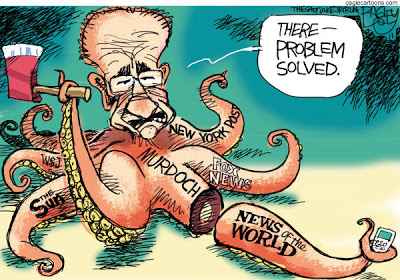

The News Corp. scandal:

A case against media consolidation

What happens when one man owns too much?

By Mary Tuma / The Rag Blog / July 21, 2011

Before a UK parliamentary hearing (and in between being attacked by a cream pie) earlier this week, media mogul Rupert Murdoch — under investigation for allegations that his recently shuttered British tabloid News of the World hacked into the phones of some 4,000 individuals and bribed police for information — stunningly absolved himself of any responsibility in the alleged illegal actions of his company.

When MP (Member of Parliament) Jim Sheridan asked Murdoch if he was ultimately responsible for the “whole fiasco,” Murdoch replied, “No,” shifting blame to those he employed and trusted. “The News of the World is less than one percent of our company. I employ 53,000 people around the world,” Murdoch retorted in defense.

Whether or not Mr. Murdoch is telling the truth, his argument — that as a head of a media conglomerate it is unreasonable to assume — due to the sheer size of the operation — that he was aware of actions, however illegal or abhorrent, within the company he owns — should trouble the public almost as much as the scandal itself.

His multi-billion dollar global media empire, stretching from TV and film to publishing and online holdings, has garnered considerable attention for its growth and scope, not to mention the political and ideological leanings of some outlets, including Fox News.

Aside from what we might think politically of the News Corporation, we can legitimately ask whether one man, or one company, should have such dominant control over our media system, the very institution we as citizens rely on to function effectively in a democracy.

Murdoch controls a wide-range of media properties like The Wall Street Journal, the New York Post, a number of cable channels including Fox News, National Geographic (part ownership), 20th Century Fox production company, film distributors Fox Searchlight Pictures, Harper Collins publishing, and some 120 international channels, according to media reform group Free Press.

The conglomerate’s expansion did not come solely by virtue of free market competition, but instead was greatly the result of a series of regulatory decisions fought hard for by Murdoch himself. The Australian born media mogul, infamous for his ruthless and ideological drive, has spent sizable energy lobbying federal regulators to relax media ownership rules in order to enable him to swallow up more media properties in more markets.

Katrina vanden Heuvel, editor of The Nation magazine, writes in a recent Washington Post editorial that, while media reform groups have battled hard to prevent the FCC and Congress from expanding media consolidation, Murdoch and his lobbyists, “have been a constant, well-funded presence — pushing to rewrite media ownership rules so that one corporation, and one man, accumulated extraordinary power.”

Dubbed the “Man Who Owns the News” by author Michael Wolff, Murdoch lives up to the moniker, having monopolized sectors of the media market with skilled leverage, even at one time securing an extremely rare waiver, not previously given to any other foreign firm at that point, which granted him license to start up U.S. broadcasting efforts. The waiver allowed Murdoch to begin Fox News while reaping the tax benefits of keeping his company in Australia.

And through all the “well-funded” wrangling, Murdoch has secured a legion of defenders in the media, an unmatched asset in a time of crisis. From leading cable network Fox News to the pages of The Wall Street Journal, Murdoch is doubly recused from guilt within the media empire he created.

The continually unfolding phone-hacking scandal shaking the UK and, to some degree, the U.S., has placed News Corp. CEO Murdoch (previously seen as “untouchable” but who has now been “mortalized”) in the hot seat — along with his son James, head of News Corp. Europe and Asia, and former News of the World editor Rebekah Brooks, among others.

With multiple arrests, mass resignations, and a company whistleblower found inexplicably dead, the News Corp. saga has effectively exposed the incestuous relationship among politicians, police, and the press — and is chipping away at the already questionable media conglomerate’s ethical credibility.

While allegations surfaced nearly six years ago, it was The Guardian’s investigation earlier this month, detailing the especially egregious instance of NOTW reporters intercepting and deleting cell phone voice messages of a 13-year old female murder victim, lending her parent’s hope that the deceased girl might still be alive, that spiked renewed and fervent interest in the claims.

Since then the scandal has not been contained to the UK, but has crossed the Atlantic, with a bipartisan coalition of U.S. lawmakers and activist groups calling on the DOJ, SEC, and FBI to investigate the media conglomerate for unethical practices including hacking into the phones of 9/11 victims and bribing foreign law enforcement.

Congressional leaders charge that the media company may have violated U.S. law under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, which holds that U.S. corporations can’t bribe or attempt to bribe foreign officials; as News Corp. is now headquartered in New York City, the law may be applicable in this case.

Yet while the dominoes continue to fall in the scandal, Brooks and Murdoch remain steadfast in their claims of ignorance to the wrongdoing, and their apologies fall short of assuming responsibility. Even Murdoch’s “We are Sorry” weekend newspaper advertisements — an attempt to save his company’s tarnished reputation — didn’t assume full liability for the actions, stating, “We are sorry for the serious wrongdoing that occurred” (and not the “wrongdoing we allowed to occur“).

Aiding in the absolution of guilt are none other than Murdoch’s vast media properties. The highly profitable Fox News Channel, owned by News Corp., stayed silent on the most prominent media story in the world when it first erupted. Unfortunately, any claims of ignorance won’t hold water: this web video caught panelists on Fox’s ostensible media criticism program, “Fox News Watch,” in a verbal game of hot potato, as all present strove to avoid responsibility for bringing up the major media scandal on the show.

When contributor Cal Thomas asked, “Anybody want to bring up the subject we’re not talking about today for the — for the [Internet] streamers?”, a second contributor encouraged Thomas to “go ahead” and raise the issue. Thomas threw the idea back at him, concluding, “I’m not going to touch it.”

Eventually Fox did cover the scandal, albeit devoting considerably less time to the issue than did its cable competitors. Even so, some of Fox’s news segments sought to dilute the criminality of the situation through the use of dubious comparisons — or simply sloughed it off as an over-reported story.

In one particularly disheartening instance a Fox host and his guest attempted to frame the controversy as a mere “hacking story” (rather than what it is, a story about journalistic ethics), by unfairly paralleling it to when Citigroup and Bank of America were hacked. They missed the mark by a long shot, only providing further evidence the network actively sought to downplay the scandal.

The Wall Street Journal, another Murdoch media outlet acquired in 2007 from the Bancroft family, ardently championed their owner’s veracity, calling the criticisms surrounding News Corp. a plot by competitors to smear the newspaper and “perhaps injure press freedom in general.” The editorial piece argued that governmental regulators, by drawing critical attention to the scandal, were essentially attacking the First Amendment, and that commercial and ideological motives are fueling the media spotlight on News Corp.

Almost mimicking their top executives’ blame-shift game, the Journal‘s piece placed British police (given they failed to enforce law) as more culpable in the illegal tampering than those who hacked the phone lines. A second WSJ article responded to accusations of the paper’s perceived ideological or commercial bias under Murdoch by citing The Simpsons’ satirical punches at Fox News. While the cartoon sitcom, produced and distributed by Fox, does occasionally poke fun at the news network, this embarrassingly weak example does little to counter the claims of bias.

It is also worthy to note that, just days earlier, WSJ publisher and CEO Les Hinton resigned his post in the midst of the phone-hacking scandal; Hinton had overseen News Corp.’s British newspaper unit during the time of the allegations. He too has pleaded ignorance to the nefarious activity, and clearly has the backing of his former colleagues. “We have no reason to doubt him, especially based on our own experience working for him,” the opinion piece read.

Similarly, News Corp.-owned The Australian, a major daily newspaper from Murdoch’s home country, claimed that a small group of elite liberal “hacks” were responsible for igniting what they called the “anti-Murdoch” campaign and bemoaned the heightened scrutiny on journalistic practices as an affront to press freedom.

Such instances of parent-company cheerleading by media are not novel and most definitely not exclusive to Fox. When it was discovered that media conglomerate General Electric did not pay federal taxes after earning some $5.1 billion dollars last year, all major media outlets but one swarmed around the story. NBC Nightly News — a GE holding — blatantly ignored the topic in its broadcast for four nights straight. NBC, of course, denies the decision had anything to do with its corporate boss.

Examples such as these are rife in corporate media culture and well documented by media watchdog organizations such as Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting.

Much of the censorship — or censorship by omission — is born from an increasingly consolidated media market. With just six major firms dominating everything we read, hear, and see (down from 50 companies in the ’80s), it is no wonder editorial pages, media criticism shows, and nightly news programs skirt around or entirely avoid critical mention of their parent companies.

The Murdoch saga affords us all an opportunity to seriously reevaluate — or at least to start paying attention to — the country’s media ownership rules. While a win for media reform activists came this month as an appeals court ruled to disallow relaxed ownership rules — and while Murdoch’s long awaited bid to acquire British Satellite company BSkyB fell through due to the scandal — the fight is far from over. Media consolidation, as activists know, hurts localism and diversity and also creates a landscape for multiple conflict of interest problems.

The UK is in the process of investigating media ownership in response to impropriety but the FCC has remained largely hands off during the scandal. The allegations may inevitably carry weight during a review of media ownership regulations by the federal agency later this year.

Just as the press held banking industry heads and BP CEO Tony Hayward accountable for dogging blame amid scandal, we too should press Murdoch — who has been granted unique and expansive rights to consolidate American media for his own financial gain — to assume responsibility.

If Murdoch refuses to take ownership of his media company’s wrongdoing, perhaps its time we take back ownership of our media.

[Rag Blog contributor Mary Tuma is also a reporter for The Texas Independent. A graduate of the University of Texas School of Journalism, Tuma has worked for The Houston Chronicle, The Texas Observer, and Community Impact Newspaper. She is in the process of obtaining her master’s degree in media studies from UT-Austin. Born and raised in Houston, she now calls Austin home. Read more articles by Mary Tuma on The Rag Blog.]