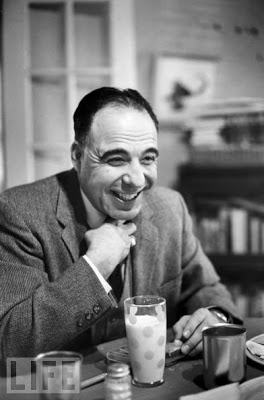

Carlos Monsivais (top), and Jose Saramago. Photos from el idiota de la familia, top, and La Nousfera.Left writers as endangered species:

Adios to Carlos Monsivais and Jose Saramago

By John Ross / The Rag Blog / July 3, 2010

MEXICO CITY — Jose Saramago and Carlos Monsivais, two writers who shared an enthusiasm for popular struggle and a mutual disaffection with the Catholic Church, were buried a few Sundays ago amidst tumultuous public acclaim.

Saramago, the first writer in the Portuguese language to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, drew tens of thousands of mourners in Lisbon, as did Monsivais in his beloved Mexico City, a megalopolis whose foibles he chronicled for a half a century.

Although the two writers held much in common — they were both writers of conviction and commitment, Quijotes who tilted at the windmills of power — they were hardly peas in a pod.

Immaculately dressed even when visiting tropical jungles, Saramago was tall and almost gaunt — only a profound sadness saved him from generalized dourness. Monsi, as he was universally pet-named around here, was short and bumptious and rumpled. So far as can be determined, Monsivais was never photographed wearing a necktie.

If one were casting them for a play it would have to be Samuel Beckett’s Waiting For Godot with Saramago in the role of Vladimir (played by the master character actor E.G. Marshall in the original Broadway production) and Estragon, portrayed by the comic Bert Lahr, “the Cowardly Lion,” both of them stranded at a crossroads in time pondering Godot’s arrival or fretful that he (she?) may have passed by before they even got there.

Saramago was not even his name. Like his father, he was a Souza, born in 1922 in the impoverished Portuguese farming town of Azingha. As the writer lovingly recalled it in The Small Memories, his father had acquired the nickname of “Saramago,” a wild radish with which poor farmers fed the bellies of their families when times were tough on the land which they always were, and when the writer’s father went to City Hall to register the birth of his new son, town officials ascribed him the surname of Saramago. It fit.

Jose Saramago grew like dry grass, bereft and barefoot. There were no books in his home and no Nobel in his future. His first novel with the flaming title of Tierra de Pecado (“Land Of Sin”) appeared in the post-World War II rush and achieved little notoriety. He did not publish again for 30 years and then inexplicably exploded, producing 32 volumes in the two decades he had left on earth.

The Year of The Death of Ricardo Reis, which put him on the literary map in 1985, is in fact his only screed in which he confronts the Salazar dictatorship that kept Portugal in chains from 1926 through 1974, the longest ruling tyranny in Europe, eventually overthrown in the Revolution of Los Claveles (“The Carnations”).

For decades, Saramago was a militant of the clandestine Portuguese Communist Party, often blacklisted and dodging Salazar’s secret police. But Jose Saramago had little taste for ideological palaver, considering himself an “hormonal communist,” an identity he fiercely maintained until he breathed his last at 87 June 18th in Lanzarote, the Canary Islands, where he lived blissfully with his translator and collaborator Pilar del Rio in self-imposed exile.

Saramago abandoned Portugal in a moment of pique after a right-wing government, at the behest of the Catholic Church (which despised the writer) refused to nominate his Gospel According To Jesus Christ for an important European literary prize. In Saramago’s Gospel, Jesus, in the throes of the Crucifixion, denounces God’s crimes against the people.

The volume earned Saramago eternal damnation by the Catholic hierarchy, which never wearied of describing the writer as “a noxious weed who has placed himself in the wheat fields of the Evangelization.” The Church, the Nobelist complained, had even denied him the right to speak with god — even if he believed god did not exist.

Similarly, Carlos Monsivais was deemed an acute thorn in the side of the Mexican Church and the pompous, all-powerful Cardinal of Mexico City Norberto Rivera whom he lampooned without mercy. Raised in a Protestant family, Monsi suffered the brunt of Catholic intolerance and never missed a chance to strip bare the Church’s fork-tongued moral message.

“I am a communist everywhere but in Mexico, I am a Zapatista,” Jose Saramago proclaimed with pride when he touched down here in 1998, his Nobel Year. The Portuguese laureate won the hearts of many Mexicans when he traveled twice to Chiapas to meet with the Zapatista rebels in defiance of President Ernesto Zedillo who threatened the writer’s arrest and deportation under Article 33 of the Mexican Constitution that provides for the removal of any non-Mexican the president deems “inconvenient.”

“If we don’t go to where the pain and the indignation are, we are not alive,” Saramago protested. “We are compelled to go to Chiapas, the center of the pain, and look into the eyes of the Indians, the survivors of all the massacres of history.” When stopped by soldiers at a roadblock in Chenalho, Saramago stood tall: “I am going to visit the Zapatistas. It my right and my obligation.”

Accompanied by Monsivais, Saramago canoodled with Subcomandante Marcos and visited the village of Acteal soon after 45 Tzotzil Indians had been massacred by paramilitaries trained and armed by the Mexican army. As he hunkered down with the farmers to hear the stories of their Via Cruces, his long, grave face darkened and Saramago’s kindly features seemed to absorb all the pain of the people.

In 2001, the Nobelist returned to Mexico to welcome Marcos and the Comandancia of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EXLN) to the capitol. As the huge Zocalo plaza filled with “the people the color of the earth,” Saramago, a kerchief of solidarity knotted around his throat, mounted to the roof of Mexico City City Hall to display his jubilation. But later, the writer would chastise Marcos for his poison pen attacks on Spanish judge Baltazar Garzon.

Jose Saramago stood with the wretched of Fanon’s earth, always at the ready to express his solidarity with those the rulers single out for punishment, whether it be the Saharan activist Aminatu Haidar, starving herself to death at the Tenerife airport because Moroccan authorities would not let her return to her homeland (his final political act) or with the Palestinian people — Saramago was designated persona non grata in Israel after decrying the treatment the Zionists inflicted on the Palestinians as a holocaust of the dimensions the Jews had suffered under the Nazis.

Carlos Monsivais, an indefatigueable “cronista” of pop culture and its intersection with social struggle, broke into the business as a teenage participant in the watershed 1968 student strike at the National Autonomous University (UNAM) in which hundreds were slaughtered by the military in the days before the Olympic Games were to begin. Along with his longtime co-conspirator Elena Poniatowska’s Noche De Tlatelolco, Monsi’s Dias De Guardar (“Days To Treasure” – 1971) denounced this act of genocide before the world.

Carlos Monsivais’s identification with the barrios and colonias of this monstrous metropolis (he himself lived practically all of his life in the San Simon barrio of the working class Portales Colonia) was the truth serum that validated his chronicles of civil society. In his No Sin Nosotros (“Not Without Us”) Monsi’s words animated the civic uprising that emerged from the ashes of the 1985 8.1 killer earthquake that felled tens of thousands here.

Carlos Monsivais was a self-confessed addict of “lost causes” (a Mexico City university once honored him with a Doctorus of Lost Causes), a Quijote-like figment who embraced every social movement to flex its fist from the 1959 railroad workers strike to gay liberation.

A disciplined, stylish writer whose baroque syntax sometimes confounded critics, Monsivais authored 50 books in 50 years, many defending popular culture against the MacDonaldization of post-NAFTA Mexico — read his final judgment in the just-published Apocalipstick. Untranslated and virtually untranslatable because his chronicles are so focused on the little things, Monsivais remains largely ignored north of the border.

Like Saramago, Monsi was fascinated by the Zapatista rebellion, penning the prologues to five volumes of EZLN documents but later quarreled with Marcos over the Sup’s gung-ho support for “ultras” who took over the 1999-2000 UNAM strike.

Although once a member of the Young Communist League, Monsi was mostly a Groucho Marxist. Unlike his Portuguese comrade, Monsivais, a critic of the cult of Fidel and Che, was not an aficionado of the Cuban revolution. Instead he walked the twisty walk of Mexican social democrats like Cuauhtemoc Cardenas in whose foiled 1988 presidential campaign he immersed himself.

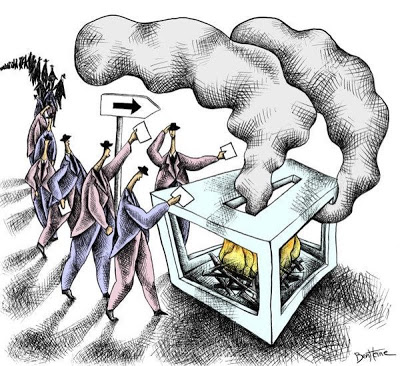

Monsi often spoke his truth from the podiums during Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador’s 2006 bid for the presidency, thwarted by Felipe Calderon and the right-wing PAN in the most fraud-mired Mexican election yet. Monsi later split with AMLO, decrying the inconveniences forced upon motorists during the left candidate’s three-week occupation of Reforma Boulevard.

Carlos Monsivais neither owned nor drove an automobile.

One of the few writers with face recognition on the streets of the city (dixit poet and pal Jose Emilio Pacheco), the sudden demise of Monsivais’s weekly assemblage of the absurdist stupidities of Mexico’s political class, “Por Mi Madre, Bohemios” (a poem his mother loved), will leave a profound pothole in the street life of Mexican journalism.

Carlos Monsivais died young enough to have been my contemporary (indeed, I was six weeks’ his senior) from pulmonary fibrosis, a disease that turns one’s lungs to cardboard. The cause of death is attributed to (a) Mexico City’s unbreathable air; (b) Monsi’s 20 beloved cats, one of whom once pissed on the world’s richest man Carlos Slim (Monsi’s family claims the cats killed him); (c) the dust and spores of antiquarian books for which the writer had an unquenchable Jones. Monsi did not smoke or drink anything more damaging to his health than jeroboams of Coca Cola.

Funerals and wakes with the “corpus presente” are organized quickly in Latin America. The climate contributes to quick spoilage and death is such a familiar feature of everyday life that when someone passes, everyone knows just what to do.

Hours after Monsi had gasped his last June 19th, friends and admirers gathered at the Museum of the City. “Viva Monsis!” echoed through the gloomy old building and white flowers showered his coffin. Mariachis tootled his favorite “rancheras” and “boleros” and writers reminisced into the dawn about their Monsi connection. Here’s mine:

A year or so after the great Mexico City earthquake that had brought me back here, I jumped into a car with Carlos Monsivais, Hector Garcia, the consummate photographer of social strife in Mexico, and Feliciano Bejar, an eccentric sculptor, bon vivant, and early environmentalist.

We were headed to Veracruz to stop the start-up of Laguna Verde, Mexico’s first and last thermo nuclear power plant. For five hours, the three artists meticulously reviewed every cantina “de mala muerte” (dive) in Mexico City, a virtual journey through the underbelly of this urban jungle I had only recently settled in.

Down in Jalapa Veracruz, Monsi schooled me in the ordering of a “Tampiquena“, a slab of thin-sliced beef with intricate accessories that is a staple of northern Veracruz cuisine. I still can’t lunch on a tampiquena without wondering if Monsi would approve.

Over the years, I consulted with the writer frequently on the social implications of the “damnificado” (earthquake victims’) movement. We shared a mutual fascination for popular anti-heroes, masked wrestlers, and the narco lord Rafael Caro Quintero who once offered to pay off Mexico’s $100 billion buck foreign debt.

In August 1994, we were both trapped beneath a sagging tent after a monumental rainstorm had ended the Zapatistas‘ Democratic National Convention deep in the Lacandon jungle. Herded into the only wooden structure on the premises, a rustic library filled with the books of Monsivais and Poniatowska, Carlos fell flat on his face and twisted his ankle painfully. When we finally raised him from the deepening muck, he was plastered with mud from scalp to socks “just like at Avandaro” (Mexico’s Woodstock) he giggled.

Carlos Monsivais was blessed with peripheral vision — “his chronicles put the marginal in the center” commented Salvador Novo, the chronicler of Mexico City life in whose footsteps young Monsi eagerly followed. Carlos Monsivais was a collector of things and people whose personal coterie included the likes of Tongolele, a pseudo Polynesian drum dancer (she was born Yolanda Montes in San Francisco), the roly-poly ranchera idol Juan Gabriel, aging sex kitten Gloria Trevi, and the hardcore feminist torch singers Chavela Vargas and Paquita La del Barrio (“Rata De Dos Patas“).

An obsessive bibliophile and tchotchke collector, Monsi prowled the flea markets of La Merced and the Lagunilla for political and pop culture memorabilia and when his Colonia Portales’ home became so cluttered with exotic bric-a-brac, he opened a museum, “El Museo del Estanquillo” (a sort of neighborhood general store), in a handsome colonial building just down the street from my rooms in the old quarter of the city.

The Estanquillo is now filled with artifacts like Mexican lottery cards, Diego Rivera’s “Dream of Sunday on the Alameda” entirely fashioned from toothpicks, Spencer Tunick’s photos of 17,000 naked chilangos (Mexico City residents), comic books featuring the down-at-the-heels Family Burron, Zapatista dolls, facsimile Adelitas (women soldiers in the Mexican revolution), the words to popular corridos (ballads), and reportedly an x-ray of Emiliano Zapata’s skull. Dead or alive, Monsi continues to thrive just down Isabel la Catolica Street.

Although Carlos Monsivais was an ardent crusader for gay, lesbian, and transgender rights, he himself was barely out of the closet, never publicly professing his sexual preferences. Nonetheless, he was an apostle of the nation’s gay liberation movement and at the official state lying-in under the rotunda at the Bellas Artes fine arts palace, when Calderon’s cultural czarina Consuelo Saizar draped a Mexican flag over Monsi’s bier, his disciples laid the rainbow flag representing sexual diversity on top of it, inciting momentary scandal.

The incident recalled Frida Kahlo’s farewell in this same spot in 1954 when the painter’s devotees rolled out a red flag with an embossed hammer and sickle upon it to the horror of Mexico’s then toxically anti-communist president (Monsi had been a witness).

Felipe Calderon himself failed to attend Carlos Monsivais’s funeral, perhaps because his nemesis Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador was programmed to appear at the same hour. At the marking of Frida’s centennial three years ago, Lopez Obrador’s supporters chased the neophyte president across the esplanade of Bellas Artes, shouting “Frida Belongs To The Left!” and necessitating military intervention.

Inside the rococo palace, the crowd chanted Monsi’s name and clenched fists shot up from wall to wall – Benito Juarez’s theme song “La Paloma” replaced “The Internationale.” When it was suggested that Monsivais be carried off to lie in state in the great Zocalo plaza where dozens of members of the Mexican Electricity Workers Union were in the 60th day of a hunger strike protesting Calderon’s privatization of electricity generation, Saizar and Education Secretary Alfonso Lujambio quickly loaded the writer’s corpse into a hearse and drove it non-stop to the incineration ovens at the Spanish Cemetery.

The next noon at a celebration of Monsivais’s life mounted by the capitol’s left government, Poniatowska poignantly asked how the city would survive without its cronista? To add a kitsch touch to the ceremonials that certainly would have tickled Monsi’s funny bone, dozens of Hari Krishnas appeared on the steps of the Theater of the City, to chant and to dance for the writer’s lively spirit.

Neither Jose Saramago nor Carlos Monsivais were much invested in the afterlife. “First you are here and then you are not,” the Portuguese Nobelist considered. When queried about what came next, Saramago described the process as “Nada. Punto.” (“Nothing. Period.”)

Saramago and Monsivais were joined in death by another of Mexico’s premium left writers, Carlos Montemayor, whose ashes were stashed in his native Parral Chihuahua, Pancho Villa’s one-time place of rest, on the same Sunday (June 20th) that tens of thousands saw off his contemporaries in Mexico City and Lisbon.

Montemayor’s novels of Mexico’s guerrilla movements, including his masterpiece War In Paradise, remain achingly pertinent today. The Chihuahua writer’s analysis of the Zapatista struggle is perhaps the most penetrating study of that indigenous uprising.

Fluent in dozens of native languages, Montemayor translated Indian poets from all over Latin America and Mexico in addition to publishing translations of Sephardic literature, and the works of Virgil, Sappho, and the Carmina Burana (he performed as an operatic tenor). Carlos Montemayor’s passing along with Saramago and Monsivais underscores just how endangered a species left writers have become in this age of scoundrels, hacks, and Pharisees.

[John Ross has lived in Mexico City for the past quarter of a century. His El Monstruo: Dread and Redemption in Mexico City (“gritty and pulsating” — the New York Post) describes this difficult passage. You can register your complaints and/or admiration at johnross@igc.org.]

The Rag Blog