|

| Political cartoon by Gary Varvel / Indianapolis Star |

Academic freedom under fire:

The Mitch Daniels/Howard Zinn kerfuffle

If education at any level is to be shaped by the principle of academic freedom it must encourage student exposure to varieties of theories, perspectives, and points of view.

By Harry Targ | The Rag Blog | August 7, 2013

WEST LAFAYETTE, Indiana — On July 17, 2013, an Associated Press story was published in several newspapers quoting from 2010 e-mails Governor Mitch Daniels of Indiana, now the president of Purdue University, wrote to “top state educational officials.” The e-mails encouraged the suppression of popular historian Howard Zinn’s book, A People’s History of the United States in Indiana public education, including university level teacher training courses.

Upon the death of popular historian Howard Zinn, Daniels e-mailed that “this terrible anti-American academic has finally passed away.”

When challenged on the seeming threats to academic freedom, Daniels claimed that his directives “only” referred to K through 12 instruction despite the fact that his e-mails made it clear he opposed instruction that used Zinn’s writings as tools for in-service training for teachers.

Ninety Purdue University faculty (including this author) signed a letter to President Daniels objecting to his implied threat to academic freedom. In addition to defending the university as a place for debate among competing ideas, the faculty objected to the negative characterization of Zinn’s scholarship as an historian.

They also objected to Daniels’ claim that although he was not interested in censoring scholarship and teaching at the university, when he was governor he had the responsibility to oversee school curricula from kindergarten through high school.

Faculty pointed out that restricting what was being taught to teachers pursuing advanced credits and restricting the right of teachers to use Zinn’s work in pre-college curricula violated academic freedom. Many Purdue faculty believed that extreme statements damning the substance of Zinn’s work cast a pall on the university and made serious reflection on American history in elementary and high schools more difficult for young people and their teachers.

It is important to note that the Daniels e-mails, and their threat to free discussion and debate in educational institutions in Indiana, reflect the deep struggles being waged in the American political system. Rush Limbaugh once remarked on his radio show to the effect that “we” have captured most institutions in the society with the exception of the university.

Since politics is usually about the contestation of ideas and the development of ideas comes from an understanding of the past and its connection to the present and the future, schools and universities can aptly be seen as “contested terrain.” That is teachers and students learn about their world through reading, writing, debating, and advocating policies, ideas, and values in educational settings.

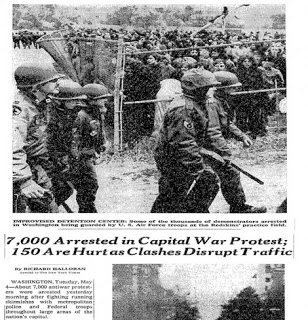

Consequently, if one sector of society wishes to gain and maintain political and economic power they might see particular value in controlling the ideas that are disseminated in educational institutions. During the dark days of the Cold War professors who had the “wrong” ideas were fired. Professional associations in many disciplines rewarded scholars who worked within accepted perspectives on history, or political science, or literature, or sociology and denied recognition to others.

The preferred ideas trickled down to primary and secondary education. In most instances, professors and teachers who suffered as a result of their teaching were merely presenting competing views so that their students would have more informed reasons for deciding on their own what interpretations of subject matter made the most sense.

American history was a prime example of how controversial teaching would become. Most historians after World War II wrote and taught about the American experience emphasizing that elites made history, men made history more than women, social movements were absent from historical change, history moved in the direction of consensus rather than conflict, and the United States always played a positive role in world history. European occupation of North America, the elimination of Native Peoples, building a powerful economy on the backs of a slave system, and a U.S. pattern of involvement in foreign wars were all ignored or slighted.

Howard Zinn, a creator and product of the intellectual turmoil of the 60s presented us with a new paradigm for examining U.S. history, indeed all history. His classic text, A People’s History of the United States, which has been read by millions, compellingly presented a view of history that highlighted the roles of indigenous people, workers, women, people of color, people of various ethnicities, and all others who were not situated at the apex of economic, political, or educational institutions.

He taught us that we needed to be engaged in the struggles that shaped people’s lives to learn what needs to be changed, how their conditions got to be what they were, and how scholar/activists might help to change the world.

Perhaps most importantly, Zinn demonstrated that participants in people’s struggles were part of a “people’s chain,” that is the long history of movements and campaigns throughout history that have sought to bring about change. As he wrote in his autobiography, You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train: A Personal History of Our Times:

What we choose to emphasize in this complex history will determine our lives. If we see only the worst, it destroys our capacity to do something. If we remember those times and places — and there are so many — where people have behaved magnificently, this gives us the energy to act, and at least the possibility of sending this spinning top of a world in a different direction.

And if we do act, in however small a way, we don’t have to wait for some grand utopian future. The future is an infinite succession of presents, and to live now as we think human beings should live, in defiance of all that is bad around us, is itself a marvelous victory.

In the 1970s the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) was formed by wealthy conservatives and corporations such as Koch Industries, ExxonMobil, and AT&T which invested millions of dollars to organize lobby groups, support selected politicians in all 50 states, create “think tanks,” and in other ways strategize about how to transform American society to increase the wealth and power of the few.

ALEC lobbyists and scholars developed programs and legislation around labor, healthcare, women’s issues, the environment, and education that were designed to reverse the progressive development of government and policy that social movements had long advocated.

Speakers at ALEC events have included Governors Rick Perry, Scott Walker, Jan Brewer, John Kasich, and Mitch Daniels. ALEC legislative programs include lobbying for charter schools, challenging teachers unions, revisiting school curricula to include materials that deny climate change, and more effectively celebrate the successes of the Bill of Rights in U.S. history.

The conservative Bradley Foundation, has awarded $400 million over the last decade to organizations supporting school vouchers, right-to-work laws, traditional marriage laws, and global warming deniers. Two of the four recipients of the organization’s 2013 award for support of “American democratic capitalism” were Roger Ailes, CEO of Fox News, and Purdue President Mitch Daniels.

Associations which lobby for restricting academic freedom in higher education include David Horowitz’s Freedom Center and the National Association of Scholars, funded by the conservative Sarah Scaife, Bradley, and Olin Foundations among others. NAS seeks to bring together scholars whose work opposes multiculturalism, affirmative action, concerns about climate change, and the “liberal” bias in academia.

NAS current president Peter Wood contributed a blog article in the Chronicle on Higher Education on July 18, 2013, entitled “Why Mitch Daniels Was Right About Howard Zinn.” Wood wrote that “a governor worth his educational salt should be calling out faculty members who cannot or will not distinguish scholarship from propaganda, or who prefer to substitute simplistic storytelling for the complexities of history.”

Howard Zinn’s A Peoples History of the United States is a history of how social movements of workers, women, people of color, native peoples, and others often left out of conventional accounts have made and can make history. This is a part of history that political and economic elites, influential organizations such as ALEC, the Bradley Foundation, and education-oriented groups like NAS do not want included in course curricula; in middle school, high school, or the university.

If education at any level is to be shaped by the principle of academic freedom it must encourage student exposure to varieties of theories, perspectives, and points of view. It is in an environment of discussion and debate that rigorous and critical thought emerges. Efforts to expunge certain scholars such as Howard Zinn from educational curricula contradict the spirit of free and rigorous thought.

A version of this essay appeared in the Fort Wayne Journal Gazette, August 5, 2013.

[Harry Targ is a professor of political science at Purdue University and is a member of the National Executive Committee of the Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism. He lives in West Lafayette, Indiana, and blogs at Diary of a Heartland Radical. Read more of Harry Targ’s articles on The Rag Blog.]