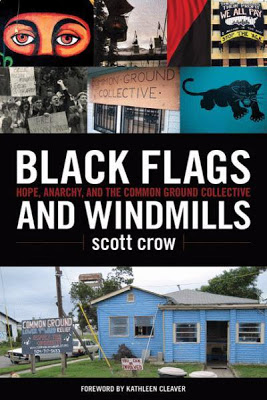

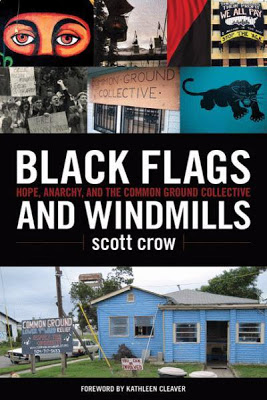

Black Flags and Windmills:

Hope, Anarchy, and the Common Ground Collective

scott crow’s book tells of the abandonment of a great American city by the powerful, the refusal of its poorest and most vulnerable citizens to lay down and die, and the necessity for community self-reliance that is Katrina’s great lesson.

By Mariann G. Wizard | The Rag Blog | December 13, 2011

[Black Flags and Windmills: Hope, Anarchy, and the Common Ground Collective by scott crow; foreword by Kathleen Cleaver (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2011); Paperback; 223 pp.; $20.00.]

On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina, a Category 3 storm, the sixth strongest recorded to date, scored a direct hit on the City of New Orleans. Over the next days and weeks, as neglected levees failed and federal and state governments and aid agencies floundered, Katrina became the costliest natural disaster, and fifth deadliest, in U.S. history.

Katrina affected millions, changed the lives of hundreds of thousands forever, and called some to rise above all personal considerations and give themselves to the Herculean task of saving the Gulf Coast and its people.

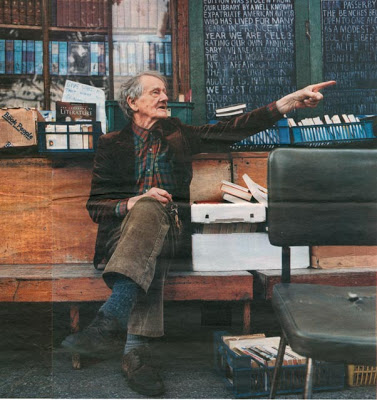

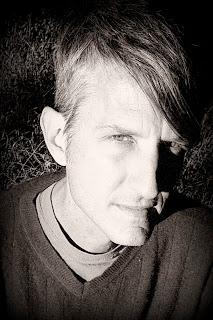

Among the latter was a Texas anarchist, a lanky East Dallas white guy who looks like he’s from way over in East Texas, easy-going but hard-bitten. And while the person he was before Katrina may still be, he was forever changed by what he witnessed and achieved in Louisiana.

scott crow, like the poets raul r. salinas and e.e. cummings, doesn’t capitalize his name. This is one of those odd contradictions, wherein a desire to de-emphasize an individual’s importance to, say, an international movement for compassionate autonomy, births the need to explain that this particular person doesn’t do something most everyone does, thus making it necessary to consider her or him individually.

Well, humility can’t help but call attention to itself, if only by its contrast with the egocentric world-at-large. As I told scott recently, I’ve been wanting to read his autobiography since I met him.

I knew his name before we met because a nonprofit foundation that I serve as a board member gave money to hurricane relief work, beginning, I think, in 2006. But I didn’t know he and his life partner, Ann Harkness, were living in Austin until they came to my book release party that fall with former Louisiana political prisoner Robert King and a couple of his other friends.

Both Ann and scott have been valuable change-makers in Austin since moving here shortly before Katrina. scott is Director of Ecology Action, the grassroots community organization that pioneered recycling in Austin while he was in grade school. Ann is a gifted, witty photographer. Both are active in many community groups and the core of a lively social scene that also embraces King, antiglobalization worker Lisa Fithian, and other activists who date their lives in Austin from Katrina’s floods.

Our community has also seen them undergo the very public trauma of having a former friend and sometime-colleague exposed as an FBI informer, in this reviewer’s opinion responsible for inciting two younger activist friends to plan violence at the 2007 Republican National Convention.

Black Flags and Windmills, crow’s first book, focuses on Common Ground Collective, an anarchist-based relief organization he helped found when official disaster relief efforts not only failed to meet the needs of affected residents along the Gulf Coast, but seemed intent upon criminalizing them.

But that wasn’t what he set out to do. While millions sat stunned, weeping at televised images of a drowned metropolis, as mythic to the American psyche as Atlantis to the Greeks’, scott crow drove from Austin, Texas, to New Orleans to look for a stranded friend.

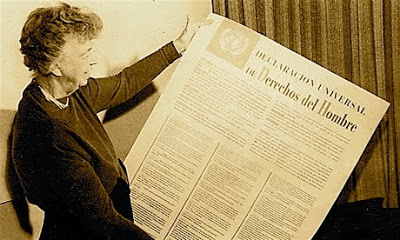

Black Panther Party matriarch Kathleen Cleaver’s insightful introduction sees this as the fulcrum, asking, “What deep motivation drives anyone to travel by boat across an unfamiliar flooded city looking for a friend under life-threatening circumstances?”

The answer comes from another BPP icon, Geronimo ji Jaga: “Revolutionaries are motivated by great love for another world.”

It is that love that most illuminates scott’s character and the pages of this work. From details of organizational process-building among a shifting cast of residents, volunteers, and core activists, to gritty descriptions of clearing long-clogged storm sewers and scraping dead animals from the streets, the bottom line is that he doesn’t leave anyone behind.

It almost doesn’t matter that the friend he went to find was Robert King, former BPP activist who served 29 years in solitary confinement in Louisiana’s notorious Angola Prison. scott and Ann Harkness met King shortly after his 2001 release. scott may not see it this way, but I think he would have done the same thing for any number of other friends and comrades.

King’s particular circumstances and his exemplary humility and dedication — he continues to work for the release of his Angola comrades, Albert Woodfox and Herman Wallace — certainly helped draw crow back to New Orleans after a first failed, frightening, surreal sortie.

The courage of NOLA residents who were also there at the beginning, Common Ground co-founders Malik Rahim and Sharon Johnson, kept him there for months under incredibly demanding circumstances. But the initial determination to help a friend underlies all of scott’s work, pre- and post-Katrina, and has made him something of an icon, if a reluctant one, to antiglobalization activists around the world.

The courage of NOLA residents who were also there at the beginning, Common Ground co-founders Malik Rahim and Sharon Johnson, kept him there for months under incredibly demanding circumstances. But the initial determination to help a friend underlies all of scott’s work, pre- and post-Katrina, and has made him something of an icon, if a reluctant one, to antiglobalization activists around the world.

As an autobiography, Black Flags and Windmills is unconventional; one must look to the “About the author” addendum to discover scott’s age. He spends 15 pages on his childhood and youth. A small, loving section on his Mom, Emily, shows the origins of his empathetic nature. It reminds me of cousins and classmates, perhaps a couple of years younger and drawn to the 1960s subculture in which I participated. Emily came to womanhood before the words “women’s” and “liberation” ever met, when racial segregation had but recently fallen, and “race mixing” was still rare.

Scott was born in 1967; the Vietnam war was still escalating. Emily, a single mom, wasn’t an activist — but she surely knew people who were. She wanted a better world for her son. I knew young parents in Austin then who sent their children to the “hippie school” in the country, or helped in a free breakfast for schoolchildren program inspired by those of the BPP. Emily sent scott to an East Dallas preschool run by former BPP activists. While the preschool was not overtly political, the BPP’s 10-Point Program is in his book and is a cornerstone of his activism.

Between East Dallas and New Orleans, scott recounts his evolution as a “libertarian anarchist,” a phrase I applaud in theory but find somewhat wanting in rigor. Despite having been influenced by socialists and socialist-influenced activists, he expresses more anti-communist views here than anti-capitalist ones, although it may be that a critique of corporate capital is implicit in the work as a whole.

He seems to view communism and/or socialism solely as political systems — authoritarian, anti-democratic ones at that — rather than economic ones. This leads him, IMHO, into the error of rejecting a priori tools that could serve a libertarian anarchist society rather well, and this is a topic I plan to pursue with him and with Ann in time.

Most of the narrative of Black Flags and Windmills, however, is not analytical but tells one man’s story — a man careful to “leave room for other stories” — of the abandonment of a great American city by the powerful, the refusal of its poorest and most vulnerable citizens to lay down and die, and the necessity for community self-reliance that is Katrina’s great lesson.

Government cannot help you. Government seeks to control you. In any disaster or emergency, help yourself and those around you. Many tasks cannot be performed by one person, thus, make principled alliances, work cooperatively, share decision-making and resources. Ask what people need; don’t assume. Express your own needs clearly.

Starting with three people and $50, Common Ground helped thousands of individuals and families, saved and rebuilt entire communities, and raised over a million dollars in small contributions in two years, an astonishing feat in the nonprofit world.

scott’s ruminations on privilege — his privileges of being white, male, able-bodied, etc. — illuminate an ongoing contradiction of radical organizing: a person on the edge of starvation has little time for considering organizational culture, yet such consideration is vital for long-term success. His solution is to use whatever social privilege he has for the benefit of those who have none.

Stretched to his physical and emotional limits, sleeping on the ground in sticky Louisiana heat, eating bad food, surrounded 24-7 by the stench of decay, death, and constant crisis, scott’s “privilege,” one may argue, is what kept him up late writing and rewriting the organizational principles, procedures, and other expressions of self-determination necessary for group cohesion.

Expecting certain rights also motivates one to demand them. scott’s experiences in New Orleans, a white outsider in a black community rightfully skeptical of offers to “help,” made me recall a personal white-girl introduction to in-your-face racism: I was furious because a friend of mine was insulted, my anger not for his humiliation, but mine. That was an expression of privilege, you betcha! — but also a time-release capsule of truth, exposing just how limited such privilege was and its unacceptable costs.

Racism continues to fester beneath public civility and political correctness today, finding sustenance in toxic, chaotic situations. The privilege of opposing it remains with the white moiety from whom it springs and whose deception is among its aims. The illusion that white skin, male gender, a college diploma, or other privileges are proof against oppression and exploitation remains a primary obstacle to social change.

crow’s frank, no-nonsense discussion of armed self-defense is also a valuable contribution; recommended. As a young man, he feared guns and had to overcome the phobia to become a good marksman when the need became clear. The East Texas in him seems to have won out here; his attitude is more that of a farmer who would resolutely drop a wild hog ripping up his crops than of a poseur power-tripping on fancy weaponry.

Again BPP principles are seen, not only in Common Ground’s acceptance of self-defense as legitimate but in the determination to keep resources gathered for the community from being stolen or destroyed.

scott is as frank in discussing Common Ground’s internal issues as its external challenges, and while his desire not to personalize problems can be frustrating to the nosy reader, the conclusions he draws are surely of more long-term value.

We don’t need to know who wanted to, “Damn everything but the circus!” to recognize the “type” scott describes in a section so subtitled: the loudmouth who shows up to “volunteer” with their own, most often self-serving agenda. Sometimes, after due consideration and an often numbing amount of talk, you just have to show them the door.

In this regard, the book is also notable for what is doesn’t include: long explanations of why scott was right and other people wrong, or details of endless debates over points that later were seen to be pointless. Through principled, shared decision-making, Common Ground has been able to grow through its occasional and inevitable disagreements relatively unscathed. It apparently furthers one to have someplace to go!

In this regard, the book is also notable for what is doesn’t include: long explanations of why scott was right and other people wrong, or details of endless debates over points that later were seen to be pointless. Through principled, shared decision-making, Common Ground has been able to grow through its occasional and inevitable disagreements relatively unscathed. It apparently furthers one to have someplace to go!

In sharp contrast to this overall amicability, crow’s brief criticism of the racist, sectarian New Black Panther Party is well-founded and pulls no punches. Two so-called “socialist” sects also come in for a well-deserved basting; a disaster area is not a place to sell your newspaper! Leaders have to speak against bullshit even when it wears a revolutionary cloak.

Yes, I said the “L” word, and so does scott: “Leadership happens when someone is given permission by the rest of the group to lead.” Accountable, anti-authoritarian leadership must be demanded, and taught. The notion that leadership is always to be avoided, a major dilettante cop-out of the 1960s, has hopefully been relegated to the dustbin of history!

Black Flags and Windmills is chock-full of juicy quotes from rebels, poets, and rockers, and has whetted my appetite to hear a bunch of bands I somehow missed, perhaps during my deeply reggae years, such as Ministry, Skinny Puppy, the Replacements, the Coup, and more.

But I was most struck by this quote from the early Romantic poet, Percy Bysshe Shelley, whose chords are echoed today by Occupation troubador Makana:

“Rise like Lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number,

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you –

Ye are many – they are few.”

— from “The Mask of Anarchy”

Another contribution of crow’s book is its Appendices, including notes, memoranda, and both internal and external Common Ground communiqués. Here are appeals to the world outside for money and materiel, desperate descriptions of need, calm accounts of the unresponsiveness and outright hostility of government and other “official” disaster personnel to the agile, popularly-based, collaborative self-help afforded by and through Common Ground.

These documents may not only be useful to historians of the future who seek to understand the impact of Katrina, or the failures of the G.W. Bush administration, but to today’s activists who seek to build new institutions, new processes, and a new culture.

No matter how dire the circumstances, it seems, this process is not easy nor always harmonious. A great deal of sweat and inconvenience is involved. Troublesome details must be constantly addressed. The more you bite off, the more you must chew. This book will help you sharpen your teeth.

Black Flags and Windmills combines hands-on information about what it really takes to change this world, one big mess at a time, and a seeker’s vision of a better world. Well done!

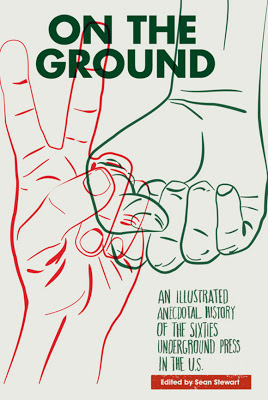

[Mariann G. Wizard, a Sixties radical activist and contributor to The Rag, Austin’s underground newspaper from the 60s and 70s, is a poet, a professional science writer specializing in natural health therapies, and a contributing editor to The Rag Blog. Read more articles and poetry by Mariann G. Wizard at The Rag Blog.]

The Rag Blog