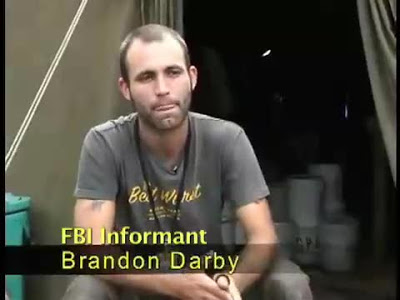

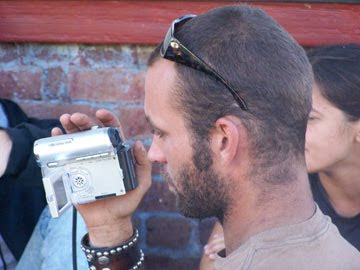

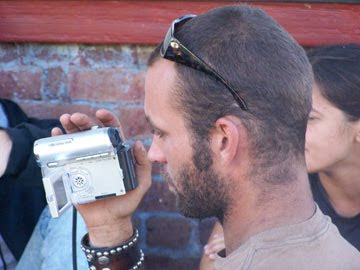

Brandon. Darby. Still from a video / videochannels.com.

Sexism, egos, and lies:

Sometimes you wake up and it is not different

By Lisa Fithian / The Rag Blog / March 22, 2010

Community organizer and nonviolent activist/trainer Lisa Fithian will be Thorne Dreyer’s guest on Rag Radio, Tuesday, March 23, 2-3 p.m. (CST) on KOOP 91.7 FM in Austin. For those outside the listening area, go here to stream the show.

[The Rag Blog has reported extensively on FBI informant Brandon Darby and the Texas 2. We have also dealt with the larger issues related to governmental use of espionage and informants. Please see links to all of our previous material at the end of this article.]

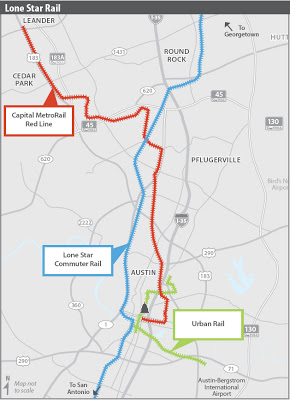

On December 31, 2008, the Austin Informant Working Group released a statement titled: “Sometimes You Wake Up and It’s Different: Statement on Brandon Darby, the ‘Unnamed’ Informant/Provocateur in the ‘Texas 2.’” It’s been over a year since then and here is my long-overdue version of that story.

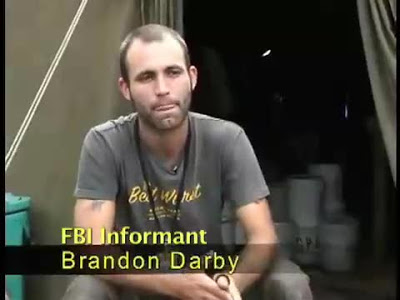

It was on December 18, 2008, that I learned unquestionably that Brandon Michael Darby, an Austin activist, was an FBI informant leading up to the 2008 Republican National Convention protests in St. Paul, MN. He was the key witness in the case of two young men from Midland, TX, Bradley Crowder (23) and David McKay (22) who, thanks to Brandon’s involvement, have been convicted of manufacturing Molotov cocktails.

They are now serving two and four years, respectively, in federal prison. In 2010, Brandon will be a key witness in another important case to the Government — the case of the RNC 8, Minneapolis organizers who are facing state conspiracy charges.

The case of the “Texas 2” gained national media attention as a result of Brandon’s unique blend of egomania, the media’s attraction to charismatic and controversial men, and the persistence of the U.S. government to criminalize and crush a growing anti-authoritarian movement. I found myself strangely entwined in the story — past, present and future.

I knew Brandon, and I was given a set of the FBI documents because, as it became apparent from reading them, I was one of the primary people he was reporting on to the FBI. (I, like many others engaged in political protest, am suspect because of my politics not my actions.) Now all of us who knew Brandon and worked closely with him, have been coming to terms with what he did, how he was able to do it, how we were used and abused in the process, and what we might do differently next time.

The Texas 2: David McKay and Bradley Crowder.

Waking up

Some of us were more surprised than others when Brandon revealed himself as an informant. My first reaction was deep sadness. I then went through a range of emotions: disbelief, shock, anger, outrage, and at times vindication. I am still hurt and angry, not just with Brandon, but with the whole system that supports and enables him.

I am still struggling with forgiveness for choices made in activist communities and by some of my friends. I understand how difficult it was; Brandon, at times, was also my friend. In the end we must examine the behavior we experienced, reflect on the array of choices we had, and explore what we could do differently to insure this does not happen again.

Brandon’s behavior was problematic long before 2008. Whether or not he was actually working for the state, he was doing their job for them by breeding discord within our politically active communities. I raised my concerns about Brandon’s behavior in New Orleans, in Austin, and also in Minneapolis.

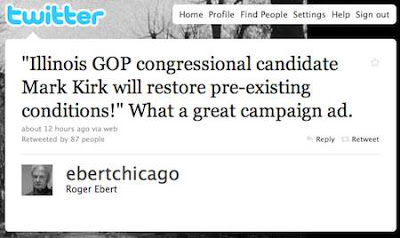

The news story broke on Thursday, December 29, when Brandon published an open letter to the community admitting he worked with the FBI. He knew we were about to blow the whistle, so he successfully preempted our headline. His initial words, however, were lies.

When asked why he got involved with the FBI, Darby said it was because he discovered that people he knew were planning violence. “Somebody had asked me to do something that would’ve resulted in hurting people, and I said no,” he said. “So they started asking other people. At that point, that’s when I went forward and contacted somebody in law enforcement.”

Darby had been involved with a group of young people from Texas who traveled together to the RNC. Their journey has become part of the fodder in the legal and media frenzy since September 2008. The trip proved to be a disaster. David and Brad ended up in jail, and the rest of the group was served Grand Jury subpoenas. The subpoenas were eventually dropped. While preparing for their trials, David and Brad both said Brandon was an informant and the community refused to heed their warnings. They felt like they knew Brandon, he’d been around for years.

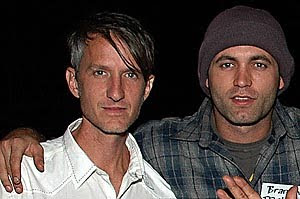

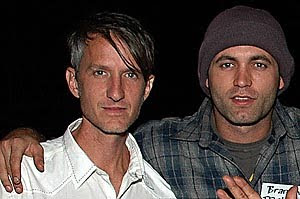

Scott Crow (left) and Brandon Darby were photographed together on Nov. 3, 2007, at a party in Austin hosted by KUT Radio. Photo from bestofneworleans.com.In November an article appeared in the

St. Paul Press asserting that Brandon Darby was an informant. This, unfortunately, was based on false evidence. Scott Crow, a friend of mine, and Brandon’s main ally in the activist community, defended Brandon calling the accusation a “COINTELPRO lie.” Little did Scott know how right he was – this whole damn thing is COINTELPRO shit.

The documents we got in December 2009 were clear — Brandon began working for the FBI in November 2007. In November 2007 Brandon had no relationship with David or Brad and could not have known their plans for the St. Paul Republican Conventions. Their plans didn’t develop until after Brandon had become an informant and after he established himself as their ally and mentor.

Furthermore, Brandon has never been squeamish about violence. He owned guns and cultivated his reputation as a hotheaded, militant revolutionary. At least a half a dozen people were prepared to testify, under oath and with some risk to them, that Brandon had approached them with proposals to commit robbery or arson. Ultimately Brandon admitted that he turned informant for the money.

Brad, David, and their families’ lives have been changed forever because these two young men were seduced and influenced by a paid FBI informant. In his early memos to the FBI, Brandon referred to them as “collateral damage.” Now these two men are spending several years of their young lives in Federal Prison.

There are many people in the activist community who have crossed Brandon’s path and have been hurt, demoralized, alienated, frightened, or run off by him. Those of us who were lied to or lied about, spied on, bullied, must deal with the trauma of his abusive behavior. We must also come to terms with the behavior of those who supported and enabled Brandon. And, as a community, we must deal with those parts of ourselves that were seduced, manipulated, and marginalized by Brandon so that we can defend each other, our political work, and ourselves.

Background

I met Brandon through his relationship with another organizer, after I moved to Austin in February 2002. Over time I learned that it was a tumultuous and abusive relationship. When it ended in 2004 Brandon moved to New Orleans for about six months. Years later Brandon told me that he had turned himself in to the New Orleans Office of the FBI when he lived there during that time. He apparently told them that he knew they were looking for him, so here he was.

It was early 2003 around the U.S. invasion of Iraq, that Brandon inserted himself in the anti-war community and gained a reputation as a paranoid guy who got himself into unusual situations with police.

During the protests on the first day of the war, Brandon was supposedly arrested for photographing undercover cops. After that action he was, mysteriously, the only person who did not want legal support. The arrest apparently does not show up in any legal records. For more on this, go here.

During this time, Brandon began showing up regularly at anti-war rallies, trainings, and other events. The anti-war community had started to use civil disobedience as a protest tactic. In the first training I did following Brandon’s supposed arrest, Brandon insisted that one of the participants was an undercover cop and demanded that I ask that person to leave. High drama around other people being undercover is behavior I’ve learned to associate with informants as a way to divert attention from them. It also breeds distrust and is destabilizing of collective efforts.

In another intense protest when UT students attempted to block an intersection with a tripod, the police unfortunately were waiting near the intersection and quickly pulled out the legs of a tri-pod, and dropped the person about 15 feet onto the pavement. Brandon who had helped bring props to the site became erratic and started yelling at the police resulting in even more people being arrested, including people who were not intending to risk arrest. Several students left the anti-war movement as a result of this action.

At this time, it became very clear that a key local organizer was being intensely targeted. Her home was broken into repeatedly. She found her vehicle tampered with, was fired from her job, and her cat was poisoned. Coincidentally, also at this time, Brandon began to court her as a mentor, asking her to teach him what she knew about organizing.

The first time she recalled meeting Brandon was the day he was arrested, when he ran up to her yelling that there were undercover cops in the crowd. Following his arrest, Brandon consistently called her, wanting to talk about his arrest and aftermath but rejecting the legal support she was helping organize. Recently, when the Austin Informant Working Group did an open records request on this organizer, the FBI found 600 documents with her name in them (they have not been relinquished by the FBI to date).

Brandon also participated in a protest at the Halliburton shareolders’ meeting in Houston. He unexpectedly joined the group intending to commit nonviolent civil disobedience. The group was on edge the night before, and now I understand why. In the planning session the night before the action, Brandon argued strongly that provoking and fighting the police was a tactic to open the eyes of the masses to police brutality, and bring more people into our cause.

He held his ground even when the group strongly disagreed and told him that under no circumstances would the group agree to him provoking or fighting the police. Brandon was a loose cannon and a bully. Even when he said he would agree to nonviolence in the action, it was clear that in his mind his agreement was contingent on the police not “provoking” him. Going into the action the next day was like sitting on a tinderbox waiting to explode.

At some actions, Brandon would show up, all masked up, with a video camera and take a lot of footage. He has continued to do this over the years, including in Minneapolis. I don’t believe he has ever posted or published any of it.

Brandon also befriended a local Palestinian activist, a man named Riad Hamad. In the spring of 2008 his house was raided by the FBI. In April Riad was found bound, gagged, and drowned in Town Lake. The death was ruled a suicide and the FBI is not releasing any information, but it was made clear in David McKay’s trial that Brandon was also involved as an FBI informant on that case.

It was in the fall of 2005 that my path became more intertwined with Brandon’s.

New Orleans and Common Ground Relief

After Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans was a post-apocalyptic state. The whole social order had collapsed. A military occupation was underway and vigilantes were literally shooting Black men in the streets. It was in the midst of this chaos that Common Ground Relief was born. The organization grew from a driveway operation into a massive grassroots response to the Katrina disaster. With ex-Black Panther Malik Rahim at the helm, it was outside of government or charity organizations, and based in direct action, mutual aid, and solidarity.

Within the first year Common Ground Relief hosted over 12,000 volunteers and established an effective grassroots relief network in New Orleans following Katrina: CG moved millions of dollars in goods and resources; set up a free medical clinic; cleaned and gutted over 1,500 homes, churches and schools; organized a free legal services, media and computer centers; revived community gardens, planted thousands of acres of wetlands and did numerous bioremediation projects.

This work was done by an incredible group of long-term organizers who committed their lives for months if not years to the work. Brandon, was part of this team of volunteers but he held a great deal of power because of efforts he and Scott Crow made in the early days of the storm to rescue a friend, Robert King Wilkerson, and to defend Malik’s home in Algiers from the white vigilantes. It was during their second trip to New Orleans that Common Ground was born.

Despite all the good accomplished by Common Ground, there was discord with other local groups and organizers who were struggling to come home. Much of the discord involved Brandon. Brandon had strong authoritarian tendencies but his lack of organizing skills and experience and his resistance to working horizontally or collectively created discord and challenges.

He insisted on being the person in charge. He demanded a chain of command with him at the top. At one point he tried to create a central committee to insure that only a select few would be in any position of power. This style put him out front whether it was the media or a group of volunteers who would be doing the heavy lifting while he talked.

For example, in the Bywater area, Brandon insisted on being the liaison to the activist community. But he treated them with such disrespect and patronization that Common Ground lost an important ally base in the local community. In another example, a local organizer was talking about putting together a women’s space and clinic. Instead of supporting that process, Brandon just moved ahead and set up a space separate from that effort, further alienating local activists.

Brandon actively agitated against any relationship between Common Ground and the People’s Hurricane Relief Fund (PHRF). He and Scott Crow, one of the co-founders of Common Ground, took a particularly hard-line position against certain members of leadership within the PHRF.

In December 2005 Brandon goaded Scott Crow to write a public letter accusing PHRF of corruption. The letter was very destructive. I had never before or since seen Malik so angry. He understood the danger of this letter and the negative impact it could have on Common Ground and the community, and he moved quickly to limit the damage.

With Common Ground Relief as his platform Brandon attempted to extend his influence internationally. He pushed for a trip to Venezuela, which made little sense and raised even more questions about Brandon, especially for those who traveled with him. In the summer of 2006 Brandon tried to initiate another emergency response and relief effort only this time in Lebanon. It was called Critical Response and was going to save the people of Lebanon from the Israeli attacks in the war with Hezebollah. Fortunately this effort never happened.

Sexism, egos and…

Brandon was a master of manipulation, and worked both women and men. He would draw them into his sometimes-twisted perspective by cultivating them through coffee, cigarettes, alcohol, revolutionary rhetoric, emotional neediness, or his physical presence — either seductive or intimidating.

Young women are often attracted to Brandon. At Common Ground, his unrestrained sexual engagement with volunteers was a problem. His “love for sex” became part of the organizational culture. His leadership role set a tone that led to systemic problems of sexual harassment and abuse at Common Ground.

When a group of the women in leadership challenged his behavior and asked that he stop sleeping with volunteers, he said “I like to fuck women, so what.” Our concerns were disregarded. The abuse became so rampant that Common Ground had to issue a public statement in May of 2006 acknowledging problems of sexual harassment in the organization.

Brandon left for a while but returned in November 2006 when he was asked to become the Interim Director of CG. His first focus was to dismantle the primarily women and queer leadership team at the St. Mary’s volunteer site. He then started recruiting men for the security team, trained them in martial arts, and asked if they were willing to carry guns, despite the fact that Common Ground had an explicit policy against weapons at our sites.

Offices of Common Ground Relief in New Orleans. Photo from BigGovernment.com.Brandon picked fights in the community, increasingly drawing police into the area and to Common Ground. He initiated action to kick down the door of the Women’s Center at two in the morning, to get rid of a man who was staying there. Brandon also kicked in the door of a trailer and pointed weapons at a group of volunteers who were hanging out with someone whom Brandon had asked to leave CG. As the Interim Director, Brandon felt he could do what he wanted without the consent of or accountability to the volunteers, the communities CG served, or other leadership.

In another incident, Brandon was arrested in a car chase. He was so angry about being arrested that Brandon once again trumped other work being done by deciding that he was going to personally clean up the New Orleans Police Department. He printed up hundreds of yard signs and put them around New Orleans, with a phone number saying that if you had a problem with NOPD, call Brandon Darby, Interim Director of Common Ground.

Brandon’s ego was getting more and more inflated making him even more dangerous. He covered his megalomania with a practiced humility and drawl. He became increasingly reckless and kept everybody in defensive and reactive postures.

Sexism, like racism, affects all of us. Brandon was allowed to assume leadership and authority at Common Ground because he was a strong, good-looking, charismatic, straight white male who was willing to take risks, even if reckless. As Malik’s favored son he did pretty much whatever he wanted. Yet, the work of activists who were women or queer or busy doing relief remained relatively invisible. Those activists were only given power where it didn’t challenge Brandon’s and he made sure of it.

During the first year of Common Ground, Brandon decided that I was an obstacle to his authority, and he worked to undermine me. He successfully diverted attention from my challenges to his sexist, abusive, unethical, and unaccountable behavior by framing them as a “power struggle”. Where he wasn’t able to convince others in the organization, he silenced them with fear of his retribution.

Brandon attacked me in public and spread disinformation about my work. He built a small group of dedicated followers that were willing to do his dirty work. They would tape record people, including myself and report back to him. He snitch-jacketed me — accused me of being an FBI agent. When I reached out to others, particularly men in New Orleans to intervene, I received little support. None of them were willing or able to challenge Brandon’s clearly destructive behavior. Those who backed his authority contributed to the organizational divisions that allowed his continued abuse of power.

In January 2007 I drove to New Orleans to pick up a friend who was kicked out of Common Ground by Brandon because she was a friend of mine. She was one of the coordinators at the St. Mary’s site. Other relief work coordinators were leaving the organization and because of this Brandon accused me of coming to town to wage a coup against him.

Early the next morning one of his “assistants” called me, threatening me with lawsuits. Then I get a call telling me that Brandon told them that King told him that Scott and I were conspiring against him. Crazy shit, crazy COINTELPRO shit. At the same time Brandon began a purge of three long-time coordinators by demanding they turn in the keys and leave the premises. But this time even Brandon went too far. Malik intervened and stopped the purge.

Lies

Brandon lies. He lied at Common Ground. He lied to the FBI. He lied in his open letter. He lied to his friends. He lied to the media. He lied to the judge and jury.

The government and the FBI lie, too. There is a long history of government infiltration and violence to disrupt social movements, a history that they have lied about in the past and they continue lie about today. It is documented that the government infiltrated and disrupted protests at the Republican National Conventions (2000 in Philly and 2004 in New York City). But in St. Paul they took it to a whole new level and they were more than willing to use Brandon to do it.

The government’s efforts to break the grassroots direct action anti-capitalist movement led to one of the most fascist operations I have experienced in the U.S. During the RNC — between knocking down doors, confiscating organizing materials, raiding homes, snatching people on the streets, impounding the skills training bus, and even surrounding my car with guns, they also arrested hundreds of innocent people and are continuing to prosecute the RNC 8, who are facing state conspiracy charges.

To this day it is my firm belief that the government set up both Brad and David, and another young man named Matt DePalma, in order to legitimize their acts of repression and to taint the environment in the case of the RNC 8. There were only two instances of Molotov cocktails in St. Paul and both of them had an FBI informant involved. In the case of Matt, the informant brought him to the library to learn how to make them, brought him to a store to buy the stuff and then made and tested them together!

In the case of David and Brad, Brandon had been goading them into a destructive mindset from the very first meeting and he continued to goad them throughout. Brandon created the environment in which they made some very bad decisions. I do not believe that those Molotov cocktails would have been made if Brandon had not been a part of that group.

One year later

At the time of this writing, Brad and David are both serving time in federal prison. Brad plea-bargained and was sentenced to two years. David went to trial and the first jury could not reach a verdict. Awaiting his second trial, prosecutors threatened to bring additional charges against Brad and to call Brad as a witness to testify against David.

Rather than force his friend to choose between self-interest and defending him, David made a decision to plea out. Instead of leniency, the judge doubled David’s sentence to four years without parole as punishment for the first trial.

Kate Kibby, who was previously arrested dressed as a zombie in a demonstration in Minneapolis.Then in November 2009 the FBI unsuccessfully prosecuted a young woman, named Kate Kibby, for allegedly threatening Brandon in an email. Fortunately, the jury delivered a unanimous not guilty verdict. One of the many interesting things we learned in that case is that Brandon had actually drafted his open letter near the end of October and posted it against the FBI’s wishes.

We also learned that one of the FBI’s motivations in pursuing this case was the hope of finding a new informant. In their interrogation of this woman, they asked if she was working with me or Scott Crow. They told her she could be facing 20 years, but more likely 2-4. If she wanted to become an informant in the Austin and New York City anarchist scenes, they could work something out.

Fortunately, this woman had integrity and principles, and refused to be threatened or bullied. Because of this, she had to endure an FBI invasion into her life, and a terrifying trial. As her father said afterwards, “I knew if we could get 12 adults to sit down and look at this, they would see how absurd it is…”

I wish that this trial could be the end of any damage that Brandon might do, but we know that Brandon is likely to be a main witness in the trial against the RNC 8, organizers from Minneapolis who are facing conspiracy charges. Who knows how many other people he will concoct stories or fabricate lies about? Or how his brain twists the facts.

After Kate’s trial he sent an email to Scott, saying that Scott and I were responsible for David being in jail. He said:

I feel that you and Lisa bear some moral (not legal) responsibility for two of the years that David McKay is serving. Y’all let your dogma and your personal resentments guide you in the advice and encouragement you gave him. He did wrong and he would be free soon had he just been honest.

Y’all somehow convinced him that he had to “fight the man” and that his being honest was somehow unfair to the oppressed peoples of the world. Thankfully, Mrs. Kibby did not take y’alls guidance or drink your koolaid- and she’s free.

A few years ago, I began to feel that you guys were similiar to radical Imams in that y’all spout hatred (not all hatred, good things too) and young activists get in trouble all around y’all, but never y’all. I feel that y’all did that with my youthful anger as well.

Though I’m sure you don’t appreciate receiving an email from me, I think you can deduce some of my motivations from its words.

I am sorry; I have worked with thousands of young people over the years and none of them are in the situation that people find themselves in after working around Brandon. I have no time for his twisted logic, vague threats and destructive behavior. Instead, let us vanquish him and learn from this to insure that he, or people like him, can never do this again. To that end…

Behaviors of Brandon’s or others that enabled this kind of damage to be done.

- Deferring or listening to men, as opposed to women and/or attacking women in leadership positions. Our patriarchal society has taught us this and we need to deconstruct it.

- Charisma and confidence enabled him to assume leadership and control — people deferred even though he had little experience. He cultivated a handful of women and men to become personal assistants who did a lot of his work for him.

- Assuming credibility by his associations — Brandon tried to associate himself with other high profile organizers in the activist community.

- Preying on and exploiting people’s vulnerabilities and insecurities, particularly using alcohol or other addictions. He liked to “play with people’s minds.”

- Bullying. All bullies abuse their power and people let them do what they want because they are afraid of what will happen if they do not go along. They use their physical prowess to intimidate both women and men.

- Disrupting group process in meetings, derailing agendas, questioning process, challenging others, or not coming to meetings at all to avoid accountability. Or using secrecy and sub-groups to divide the whole.

- Pointing fingers at and ‘snitch-jacketing’ other people, accusing them of being cops, FBI agents, etc. This kept everyone on guard, and created an environment of suspicion and distrust.

- Seducing people using power or sex, leaving a lot of pain and destabilized situations in his wake or provoking people to do acts they would not do on their own.

- Being persistent and pursuing people, by calling them repeatedly or showing up at their homes, inviting them for coffee, he would wear you down, or find other ways back into important relationships.

- Being an emotional/physical wreck, becoming very needy and seducing people into taking care of him. Then people would defend him because of his emotional vulnerabilities or physical needs.

- Time and energy suck. Talk endlessly, consuming hours of time and energy — confusing, exhausting, and indoctrinating.

- Being helpful or useful — showing up when you most needed support. Brandon would arrive with tools, money, or whatever was needed at just the right time.

- Documenting through videotaping or photographing actions but never using it or working on communications systems which he attempted at the RNC.

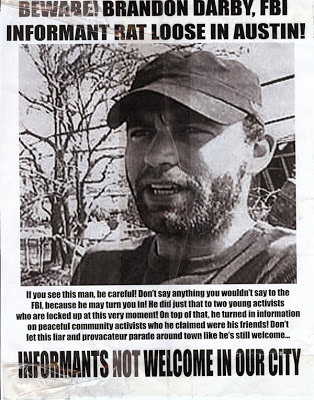

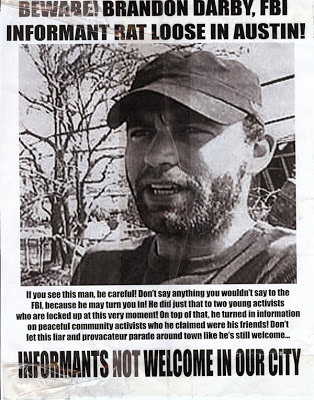

Brandon Darby at work. Image from New Orleans Indymedia.

Some day I hope to wake up and find things different

Brandon’s behavior over the years makes it clear that he is a misogynist, an egomaniac, and a liar. Unfortunately, many in our broader community bought into the illusion that he was a great radical self-described “revolutionary.” They defended him again and again. He repaid their support with betrayal. He continues to make a mockery of our work and supports the FBI in their efforts to crush our struggle for justice.

Some day I hope to wake up and find things different. I hope to see our communities deepen our understanding and commitment to uprooting all the “isms.” I would like to see a community where we create agreements and structures of accountability that will not allow behaviors like those highlighted above to continue, and if they do continue, that men will listen to women, and stand up to each other when someone is clearly abusing their power and authority.

In the end, I do not know what other choices I could have made short of leaving Common Ground earlier. I actually believe I tried to interrupt, make visible, warn and mitigate the damage of Brandon, but it was the people around me that continued to support Brandon despite the obvious problems.

Some of the lessons I have learned are that if someone is continually engaging in a pattern of disruptive behavior, like those mentioned above, that people must make clear agreements about what kind of behavior is OK and not OK and then collectively hold each other to those agreements.

If people/women are continually raising an issue about a particular person I will pay more attention, do some research, and if questions or problems continue to arise about that person, I will work together with others to ask that person to leave. Whether they are infiltrators or not, the behaviors that they are exhibiting are counterproductive to a world rooted in justice and equality. They are also, by their very nature, putting all of us at risk of unjust government action and imprisonment by their reckless and provocative behavior.

I also hope that someday when I wake up that I will live in a world where people do not use the threat of or use of violence to get their way or impose their will. That if we have such people in our movement that we will not be intimidated but instead will work together to end those abuses of power, for they mirror the abuses the Government in their efforts to exploit and control.

I also hope more people will chose nonviolent action since such action prefigures our future, can be strategically effective, and minimizes our movement’s vulnerability — and because I do not believe we can make lasting real radical change through violent means in this country.

Some day when I wake up, I hope to find an end to the systemic oppression and repression that unjustly locks up so many innocent people, while destroying and thwarting the dreams of so many others. Perhaps if we built our communities based on just agreements and real accountability, prisons would become obsolete.

Until we wake up in that world, let us remember that no one is free until we all are free. No day will be different until we make it so. Let us begin today.

Here is a link to a story about a long-time informant in New Zealand that also made the news in December 2008. It is uncanny how many similarities there are and lots of good lessons for us…http://indymedia.org.nz/newswire/display/76563/index.php

A great deal has been written about the case of the Texas 2 and can be found at www.freethetexas2.org

Many thanks to the following for their editorial support: James Clark, Lauren Ross, Ted German, Casey Pritchett, Scott Crow, and Missy Benavidez.

[Lisa Fithian has been organizing for 35 years — working with peace, labor, student/youth, immigrant and global, environmental and racial justice organizations and movements. Much of her work has been focused on using creative nonviolent direct action and civil disobedience in strategic campaigns. She is a member of the Alliance of Community Trainers, a small collective working to empower communities for collective transformation.

Lisa has worked with Common Ground Relief, the post-Katrina New Orleans collective; the new Students for a Democratic Society (SDS); United for Peace and Justice; and environmental groups like Save our Springs — and she helped Cindy Sheehan coordinate activities at Camp Casey. Check out Lisa’s websites: www.organizingforpower.org and www.trainersalliance.org.]

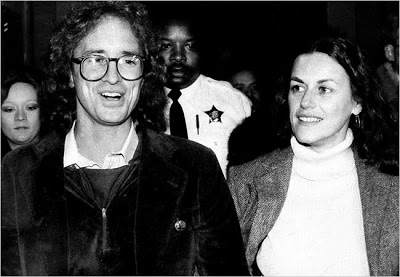

Top: Lauren Ross, center, is comforted by her friend Lisa Fithian after they were arrested during a protest in New York Sept. 2, 2004. Photo by Bebeto Matthews / AP. Image from CommonDreams. Below: Lisa Fithian and Ken Butigan at a National Assembly of United for Peace and Justice in Chicago, 2007. Photo by Diane Greene Lent / dianelent.com.

Top: Lauren Ross, center, is comforted by her friend Lisa Fithian after they were arrested during a protest in New York Sept. 2, 2004. Photo by Bebeto Matthews / AP. Image from CommonDreams. Below: Lisa Fithian and Ken Butigan at a National Assembly of United for Peace and Justice in Chicago, 2007. Photo by Diane Greene Lent / dianelent.com.

Previous Rag Blog articles on Brandon Darby and the Texas 2:

Go to the Support the Texas 2 website.

And listen to “Turncoat,” a story about Brandon Darby on Chicago Public Radio’s This American Life. [The Darby segment starts 13 minutes in.]

Also, read this remarkable piece of reporting: The Informant: Revolutionary to rat: The uneasy journey of Brandon Darby by Diana Welch / Austin Chronicle / Jan. 23, 2009

For more background on the history of informants in Texas, read The Spies of Texas by Thorne Dreyer / The Texas Observer / Nov. 17, 2006.

And see the entire “Hamilton Files” of former UT-Austin police chief Allen Hamilton that served as documentation for Dreyer’s story, here.

The Rag Blog