The hill (and beyond). Image from Financial Samurai.

Do not be dismayed:

The view from over the hill

Even in defeat we are victorious, for we have given our lives a meaning others should envy. In struggling for something greater than ourselves, we will be transformed.

By David McReynolds / The Rag Blog / May 10, 2011

[On April 26, 2011, there was a book party in New York City for Martin Duberman’s double biography of Barbara Deming and David McReynolds, titled A Saving Remnant. (Read Doug Ireland’s review of A Saving Remnant on The Rag Blog, and listen to Thorne Dreyer’s interview with McReynolds and Duberman on Rag Radio.) The following article is based on remarks delivered by David McReynolds at that event and notes he made the next day.]

I’m reminded of the day, hitchhiking to UCLA from my parent’s home in Southwest Los Angeles, when I was picked up by a pleasant elderly gentleman with a head of white hair.

At the time I was involved in one of those affairs of the heart which wasn’t going at all well, and I thought, as I looked at the old fellow, how good it must be to be old, past the burdens of the flesh, able to enjoy good food and fine wines, visit museums.

Just then he reached over, put a hand on my thigh and said, “A tall young man like you, I expect you play basketball.” As I gently removed his hand and said I didn’t play any sports, I wanted to tell him that he had destroyed my illusions of old age.

In fact, in reading Marty’s book, which I felt treated me not only accurately but very gently, I sense I probably am less stressed these days than when I was young.

Certainly it is a great honor to find that while you are still alive you are subject of a biography — moreover, one which links you with that major figure of the last century, Barbara Deming. If I do not here deal with the issue of feminism, it is because Barbara dealt with it so well and I refer you to Marty’s book to get her views, with which I am largely in agreement.

It has been a good life in which, looking back, I am moved by the thought that at one time or another I walked in the company of giants such as Alvin Ailey, Norma Becker, Karl Bissinger, Maris Cakars, Sam Coleman, Dave Dellinger, Barbara Deming, Ralph DiGia, William Douthard, Peggy Duff, Allen Ginsberg, Gil Green, Arthur Kinoy, A.J. Muste, Grace Paley, Igal Roodenko, Bayard Rustin, Myrtle Solomon, and Norman Thomas. And was arrested with more than half of them.

I am deeply moved by those who organized this event and by WRL, which put up with me for nearly four decades, and the Socialist Party, which twice honored me with their nomination for President. Given the limits of time, I want to move directly to seven points.

First, do not be dismayed that we are in such troubled time. Large numbers of Americans seem impressed by Sarah Palin, Glenn Beck, or Donald Trump. Would you rather have found yourselves in a comfortable time when your voice wasn’t needed?

Think back to the other times we have lived through. The great war for Four Freedoms when we put Japanese in concentration camps on the West Coast. McCarthyism, when people were jailed for their political beliefs.

I remember, at UCLA, a group of us young radicals met at the beach shack in Ocean Park, 132 ½ Ashland Ave., for a serious discussion of whether we should not all leave for Costa Rica. One of us was taking flying lessons, and one of us was arranging for renting or buying a plane.

We voted not to go — though we were convinced we would all end in prison, as indeed some of my close friends at the time, Vern Davidson and others, did, for refusing the draft. Think of the fact that south of the Mason-Dixon line whites and blacks were separated on buses and trains, and blacks in the South had no vote.

Second, my life has been given to trying to find some combination of Marx and Gandhi. In this I have failed, but let me explain why that effort must continue. Do not blame Marx for Stalin, any more than you can blame Jesus for the Inquisition, or Gandhi for India s nuclear weapons.

Marx showed us that whereas in all previous times we had been the objects on which history was imposed, we now had the chance to consciously enter history as the subjects of it, who could act to change it.

It was Marx who taught us that the future is inevitable, is in our hands. Who helped us see how our consciousness is shaped by the class we are born into, the color of our skin, and, more than Marx realized, the sex we are given. It was Marx who suggested that the great issue is over who controls the means of production, whether they are in the hands of a few, or in some democratic way, in the hands of the many.

Marx came before the Russian Revolution. His vision was not that of the totalitarian state of Stalin, but of a broad and democratic society, one in which we could move from a society of need to one of abundance.

Yes, there were errors in Marx, a failure to examine the problem of the patriarchy, a failure to see the limits beyond which the exploitation of nature could lead to ecological disaster. But it was Marx who taught us we could take charge of our history.

Third, Gandhi gave us the solution to how we can engage in struggle without letting that struggle destroy us. In taking the path of violence, we find ourselves pitted against our brothers and sisters, we find ourselves dealing out murder in hopes of establishing the loving community, of building prisons in hopes we will find universal freedom.

It was Gandhi who reminded us that the means becomes the end. If your method is an organization which hates your opponents, so will the society you construct be shaped by hatred and not by compassion. I am not going to distance myself from those who are violent revolutionaries — it was Gandhi who felt that it was better to resist by violence than not to resist at all.

Pacifism is not for cowards. In fact, one of the main problems I had in becoming, or trying to become, a pacifist was that I knew I lacked the courage needed. In the end, looking back at a life in which I have suffered little for my beliefs, I conclude that God watches over atheists and cowards. We are not required to march farther than we are able, but to at least to take the few steps we can.

It was Gandhi who taught us a lesson which had been there all along, in the Gospels, in the teachings of Buddha, that there is a power in love, or, if you find it easier, the power of compassion. There are some few who we can be exempt from that command — Donald Trump has so much love for himself that he hardly needs mine.

But, friends and comrades, when A.J. Muste stood in a Quaker meeting during World War II and said, “If I cannot love Hitler I cannot love anyone,” do not think Muste was naive about Hitler. If we cannot find compassion for our enemies, we are lost.

Bayard Rustin explained it to me as the soldiers in a foxhole, when a volunteer was needed for an errand which might well be fatal, and the soldier who volunteered did so because, as he looked around at the others with him — one whom he knew was too terrified to make the run safely, one who had a wife waiting him, one who might falter because of an earlier wound — said to himself, let it be me. And all that pacifism does is extend that foxhole to include also the enemies.

David McReynolds at the 2009 Left Forum in New York City. Photo from Wikimedia Commons.This is not an easy teaching. But it is essential, along with Gandhi’s absolute passion for truth — for holding onto the truth, for basing his analysis on the facts, for being willing to change his mind. This passion for observing the facts and then reaching conclusions was something he held in common with Karl Marx.

The great light that helps us keep life in perspective is death itself. For there is an end for each of us, but not for all of us together, as a human race feeling its way toward the future. All that we really have along this path is compassion and truth.

Think of the power of the Southern Black movement, largely rooted in the Black Church, which not only gave us the blues and jazz, but the extraordinary power of revolutionary change through taking the risks of change through nonviolence. How lucky I have been to have seen a part of that light cast upon America.

Fourth, we are engaged in a struggle to empower the powerless. It has been said that power corrupts, and that is true. But it is easy for pacifists, most of us safely from the white middle class, to overlook the reality that powerlessness also corrupts. Our struggle is not to seize power and centralize it, but to decentralize it, to empower the communities and the people.

Power is a reality. The power to build railroads and dams, to find alternative sources of energy, to build housing for the poor. We want to eliminate the monopoly of power which exists today. The power to make war, to imprison the powerless.

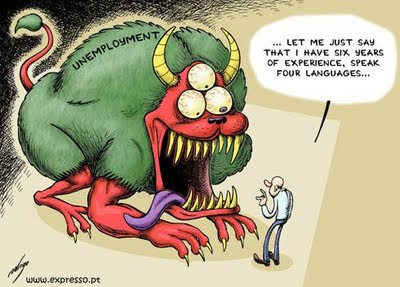

I do not, I’m sorry to say, have the answers. At 81 it is enough if I can suggest the problems. It is clear capitalism has failed, that we have seen a steady, relentless concentration of wealth and power in the hands of the few, while the great mass have less economic security.

Fifth, we also need to struggle to take power away from those who have it. At the moment the United States is still the most powerful military force in the world. We have deluded ourselves with the talk of representing the free world.

What our military power has been used for is the defense of America s economic interests, and on some occasions, out of sheer folly and stupidity. We have in the past 50 years waged wars against nations that never fired a bullet in any of our 50 states or posed any real threat. Korea, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Panama, Grenada, Serbia, Iraq, Afghanistan.

I do not defend those nations but only note our military actions cannot be justified by threats they posed to us. We have killed millions. And we have killed them with weapons created with great skill, from the drones that fly over Pakistan, to the pellet bombs used in Vietnam.

No other nation can match our record of slaughter in the past 50 years.

Sixth, we are truly two Americas. Both in the sense that the late Michael Harrington laid out so well, the nation of wealth coexisting with the nation of poverty, but also the nation of men and women willing to devise the arsenal of death so recklessly used by the elite which governs us, and the nation of women and men willing to vigil, to organize against, to suffer jail for, their opposition to this America of violence and death.

Remember, at this dark time when Donald Trump can score so well in opinion polls, that this is a nation which survived slavery, the Palmer Raids, and McCarthyism. Our hope lies in our willingness to withhold consent, to refuse to be frightened.

It takes courage to confront the worst of this nation and this world — the cowardice of a President, and a British Prime Minister and a French head of State, not one of whom has seen combat, to send others into battle in Libya — and yet to hold onto hope. Hope has been defined as the combination resulting from combining anger with courage.

Even to believe that in the hearts and minds of our opponents there is the possibility of change.

One of the lessons in the Gospels is that no one is beyond hope. Jesus, in his ministry, did not sit with us, but chose to sit with agents of the IRS, and the FBI, to break bread with the bigots. So let us, in our community work, not disdain our enemies but dialogue with them.

Keep in mind that the Tea Party folks are largely middle aged, almost entirely white and Christian, and confused to find their President is black, the Secretary of State is a woman, there is a lesbian commentator on MSNBC cable, and the society pages record men getting married to men, and women getting married to women. The reality is that in a short time whites will be a minority in this country. And there is great fear of this final shift in our nation.

Seventh, let each of us take on the task we can. We are not observers, but participants. That may not mean joining an organization, but it means realizing that organizations are needed. Your work may range from being a good parent – a work of great courage and skill — to being a good artisan or artist, or teacher.

But we are united in rejecting the assumption that the accumulation of wealth is the object of our lives.

And in this task of building a movement for change, let us build it based on the uniqueness of this country, and not on patterns others have set. The lessons of the Russian Revolution do not prove a guide for us. Gandhi’s tactics in India are not a guide to us.

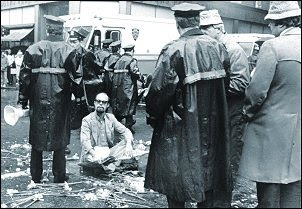

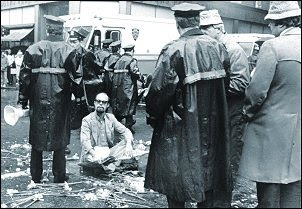

Above, a group of protestors against the War in Vietnam, including David McReynolds (the tall one), burn their draft cards in Union Square, New York, November 5, 1965. (Left to right: Tom Cornell, Mark Edelman, Roy Lisker, McReynolds, Jim Wilson, and A.J. Muste.) Image from Ferment Magazine. Below, McReynolds at Armed Forces Day Parade, 1979. Photo by Grace Hedemann / Nonviolent Activist.Remember that American socialism was a real force before the Russian Revolution and that the greatest example of nonviolence in this nation did not come from the white pacifists, but from the Black Churches in the South.

Eugene V. Debs is an example of someone who tried to shape a movement based on the exceptionalism of this country, as A.J. Muste also did. Remember, each country is unique and exceptional.

Finally, let me say that we really do not know if we will win or lose. That, depending on your philosophy or religion, is in the hands of history or of God.

But we do know that our lives are defined by having been part of the endless struggle. For Gandhi knew, and Marx knew, that conflict does not end. We can hope, in the words of the old joke, that when we came to this seminar we were confused and uncertain, but we are happy to say, on the conclusion of our weekend of study, that we are confused on a higher level and uncertain about more important things .

The joy of those who flooded Madison, Wisconsin, in the struggle for worker s rights; the joy of those who marched in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963, when the streets were filled with hundreds of thousands; the joy of the May Days in 1971 when 15,000 of us were arrested and tear gas floated over the city.

Those were great times — and better times lie ahead. Even in defeat we are victorious, for we have given our lives a meaning others should envy. In struggling for something greater than ourselves, we will be transformed.

And if I have not, in this speech, addressed the questions of gender and gay liberation, let me close by quoting my old friend, Allen Ginsberg, in saying, “America, I am putting my queer shoulder to the wheel.”

Postscript

Reading over these notes I am struck by omissions that were inevitable but need to be briefly discussed.

I do not think socialism must be Marxist . There is religious socialism, utopian socialism, libertarian socialism. I simply want to affirm the debt we owe to Marx and Engels. I do not believe Marxism to be scientific socialism. It is said that at one point an exasperated Marx said, “Thank God I am not a Marxist.”

Lenin, whose views I respect even though I disagree with them, was quite right when he wrote, “Marxism is not a lifeless dogma, not a completed, ready-made immutable doctrine, but a living guide to action.”

But what is socialism? What would it look like? Marx himself was vague on this, and what set him apart from the utopian socialists (who were not, let me note, without a value of their own) was his awareness that social change is a process, not a blueprint.

The closest he came to defining socialism was in his Critique of the Gotha Program. But even to take that up is to waste time — it was written long before the Russian Revolution, long before all of the trauma of the technological and cybernetic revolutions.

The closest he came to defining socialism was in his Critique of the Gotha Program. But even to take that up is to waste time — it was written long before the Russian Revolution, long before all of the trauma of the technological and cybernetic revolutions.

We can say that socialism is a way of organizing the economy so that the major means of production are socially owned and democratically controlled. We can say that great fortunes would be a thing of the past, that the huge concentrations of wealth as they exist now would end with estate taxes.

But we can also say that socialism does not mean there will be no small business. Ironically it is capitalism which has proven the great enemy of small business. Socialism does not mean your apartment or your home or your family farm will be seized, much less your toothbrush. Private property would not be abolished. It would be social property which would be dealt with.

Even this, however, requires a lot of new thinking. Our own society today has few great factories that can be turned over to the workers. To a great extent we have become a society of service industries. Ironically our farming is perhaps more collectivized (by large farming corporations) than was true even in the Soviet Union. Socialists might want to find incentives for the revival of family farms.

We can certainly look at the mistakes (and the successes) in the Soviet Union, of the social democracies of the Nordic countries, of Cuba, of China, etc. but we are so very far from having the political power to achieve socialism that it is pointless to waste enormous time now over debating the blueprints.

Clearly — because our survival depends on it — whatever socialism we struggle to create must have much more concern with ecology than the socialist movements of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Economics, whether Marxist, Keynesian, or free market, is extremely complex and extremely unpredictable. What is clear, and has been clear for some time, is that capitalism is a failure.

This has been dramatically shown with the most recent collapse of the free market but it is also inherent in capitalism that human beings become commodities, that they are driven to compete, often wasting their lives in activity that has almost no social or intrinsic value (advertising, dealing in commodities, etc.). Capitalism produces a society in which authentic human freedom is hard to achieve.

Finally, the other necessary postscript concerns How. Not just what is socialism, but how do we get there. Marx thought socialism would come when in the final crisis and collapse of capitalism, the workers would seize power. He was sure that the birth of the new order would be bloody — and he had history on his side, since all other major shifts in how society was organized took place with great violence.

It was not that Marx hoped for violence, simply that he thought it inevitable. (And I might add that if one adds up the millions of lives destroyed in wars due primarily to capitalism, then the violence of revolution looks a bit different).

However the Russian experiment is instructive and tragic. Without trying to reprise that history here, the enormously liberating experience of the first years of the Revolution were replaced by secret police, prisons, brutal repression, and the hideous conformity of Stalinism. Even more sadly, with the collapse of the Soviet Bloc we have seen little remaining that is of value.

It is easy for the ultra-revolutionists to argue for a violent revolution, but I believe, with Debs, that if workers cannot learn to aim their ballots, they wouldn’t aim their bullets any better. Aside from which, a violent revolution inevitably falls upon the young and strong, while a nonviolent revolution is one in which all, young and old, weak and strong, can take part.

In the United States even Karl Marx had thought that it was possible for profound social change to occur through elections.

At this point there is no single party which represents democratic socialism. And we need to think less of parties in the usual sense than of organization, which can educate and organize demonstrations (and civil disobedience) as well as enter the electoral field.

There are groups today which might with profit work more closely together — the Socialist Party, Democratic Socialists of America, the Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism, would be in this grouping. Nor would I exclude the Greens from dialogue. Nor would I exclude the Communist Party, which is going through serious internal changes.

A final word before the postscript becomes an entirely new venture rather than simply an effort to clarify. While I have no interest of any kind in the Vatican, one must remember figures such as Pope John XXIII, Dorothy Day, the quiet revolutionaries of the Catholic Worker — and of other Christian groups.

And if one despairs at much of the Jewish community for its rigid approach to issues such as Palestinian rights, there are groups such as Jews for Racial and Economic Justice (as well as several others working for peace in the Middle East) which remind us that a rigidly atheist socialist movement will pointlessly isolate itself. Judaism, more than most religions, is based on the concept of law and community.

Marx represented, I realize, an atheist approach to society, and as such he was the enemy not only of capital but of all religious bodies. But Marx was not, himself, a God. On the contrary he dealt with contradictions, as did Gandhi. It may baffle the orthodox mind, but it is quite possible to embrace a generally Marxian approach and also a Christian, Jewish, or Islamic set of beliefs.

Let those who would be offended by this willingness to link spiritual values with material struggle be offended — it is still possible and needs to be said.

Finally, pacifists must not simply resist violence, but seek to build a society which does not treat people violently. If we are not inherently a philosophy of radical social change, I think we have little value. But if we make ourselves a part of a broader movement, most of which may well not be pacifist, we can help to resolve the conflicts, and make dialogue an alternative to endless fracturing and splits.

We may, as people committed to reconciliation, shy from the terrible reality of the class struggle, but there is indeed a class struggle or class war, and as Warren Buffet said, “There is a class war and my class is winning it” (and he wasn’t happy about it — the concentration of economic power in so few hands is profoundly alien to democracy).

The only people who don’t know there is a class war are those at a safe distance from it. Think of it as a war against injustice, but it is real, and we must take our part in it.

A final point (like all radicals, one’s final point is never quite final) concerns State and Government. They are confused by most people who view socialism as the State taking charge of their lives.

There is a crucial difference between the State, which has the power to wage wars and to execute people, and the Government, which collects garbage, educates our children, maintains public safety, builds bridges, and in many other ways does those things which individuals alone cannot do, and which we do not feel comfortable having done for a profit.

Governments can be very decentralized, States tend to seek an absolute monopoly of power. I would hope the democratic socialism we seek is one of diffused power.

(Now you may think this is the end. And it is.)

[David McReynolds is a former chair of War Resisters International, and was the Socialist Party candidate for President in 1980 and 2000. He is retired and lives with two cats on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. He posts at Edge Left and can be reached at dmcreynolds@nyc.rr.com. Read more articles by David McReynolds on The Rag Blog.]

The Rag Blog